Introduction to Lhasa’s Cultural Tapestry

Lhasa, often referred to as the “Land of the Gods,” is a sacred city nestled on the Tibetan Plateau, renowned for its profound significance in Tibetan Buddhism. Serving as the spiritual and administrative heart of Tibet, Lhasa is home to the iconic Potala Palace and Jokhang Temple, stunning examples of Buddhist architecture and devotion. However, beyond the well-trodden paths of pilgrims and tourists lies a tapestry of cultural diversity that often goes unrecognized.

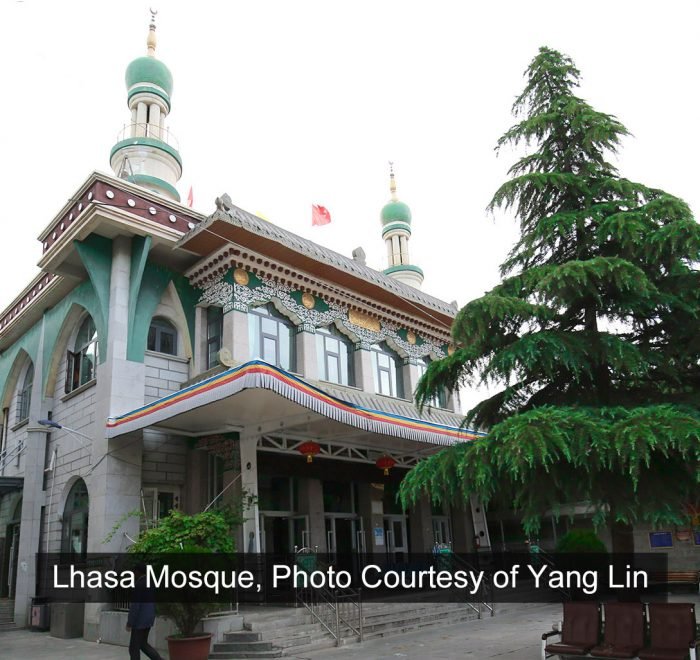

This cultural confluence is particularly evident in the city’s mosques, which stand as testaments to the historical interactions between Tibetan, Islamic, and Han cultures. Lhasa’s mosques not only serve the needs of the local Muslim community but also reflect the historical journeys of merchants, travelers, and immigrants who have traversed the region over centuries. The architectural design of these mosques often incorporates local artistic elements, blending traditional Tibetan styles with Islamic motifs, creating a unique architectural dialogue that showcases Lhasa’s multifaceted identity.

As we delve deeper into the exploration of Lhasa’s mosques, it becomes evident that this city is not just a sacred stronghold of Buddhism, but rather a vibrant mosaic of diverse beliefs coming together, enriching the cultural narrative of the Roof of the World.

Lhasa’s Islamic Landmarks: A Tour of the Four Mosques

Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, is characterized by its rich tapestry of cultures and religions, including a notable Islamic presence reflected in its mosques. Among the four prominent mosques in the city, each serves as a crucial landmark for the local Muslim community, offering places of worship, cultural exchange, and historical significance.

The first mosque, the Id Gah Mosque, stands as the most significant and oldest Islamic site in Lhasa, dating back to the early 18th century. Located in the northern part of the city, this mosque is known for its serene ambiance and architectural simplicity, featuring traditional Tibetan influences. Despite its modest size, the Id Gah Mosque plays a vital role during Ramadan, hosting communal prayers and festivities that unite the local Muslim population.

Jamia Mosque

Next, the Jamia Mosque emerges as a central religious hub for the city’s Muslims. Constructed in the late 20th century, this mosque’s architectural design is more contemporary, featuring a blend of Islamic and Tibetan styles. It is strategically located in the bustling Barkhor area, making it easily accessible to both residents and tourists. The Jamia Mosque hosts educational programs and provides a support network for the community, focusing on the preservation of Islamic traditions within the unique Tibetan context.

Another notable mosque is the Apang Mosque, distinguished by its striking brick-and-plaster façade. It is commonly frequented by the local Hui community and offers a welcoming environment for visitors. This mosque, which incorporates elements of Tibetan aesthetics, serves not only as a place of worship but also as a venue for cultural festivals that highlight the harmonious coexistence of Tibetan and Muslim traditions.

Lastly, the Langkor Mosque adds to the cultural diversity of Lhasa. Though smaller than its counterparts, it plays an integral role in serving the local population. Situated in a quieter area, the Langkor Mosque is often sought out for more intimate prayers and community gatherings, reinforcing the deep-rooted bond among the local Muslims.

Each of these mosques contributes to Lhasa’s vibrant cultural landscape, showcasing the rich heritage and communal spirit of its Islamic communities. Their historical significance and architectural diversity serve as a testament to the confluence of cultures in this unique region of the world.

Hebalin Mosque: The Heart of Lhasa’s Islamic Community

The Hebalin Mosque, prominently situated in the vibrant city of Lhasa, stands as the largest mosque in the Tibetan region. Its historical timeline traces back to the late 18th century when it was initially constructed to accommodate the growing Muslim population in Lhasa. Throughout the years, the mosque has undergone several renovations and expansions, reflecting the resilience and dedication of the local Islamic community. Today, it serves not only as a place of worship but also as a focal point for social gatherings, education, and cultural exchange.

The architectural design of the Hebalin Mosque is a testament to the harmonious blend of diverse cultural influences. The mosque merges traditional Islamic features with those of Tibetan and Han architectural styles, resulting in an aesthetic that is both unique and representative of the region’s multicultural fabric. The mosque’s distinctive dome and minaret, coupled with intricate carvings and beautiful calligraphy, illustrate the exquisite craftsmanship that has characterized the building over centuries. The use of vibrant colors and detailed motifs enhances the mosque’s spiritual ambiance, making it a place of tranquility and reflection for worshippers.

Culturally, the Hebalin Mosque holds significant importance for the Muslim community in Lhasa. It serves as a vital center for Islamic education, where religious teachings and cultural practices are passed down through generations. Regular worship, community events, and celebrations during Islamic holidays foster a sense of belonging among the local Muslims, enriching Lhasa’s diverse cultural panorama. This mosque not only stands as a place of prayer but also acts as a symbol of unity and coexistence, embodying the spirit of tolerance and mutual respect that characterizes Lhasa’s multicultural society.

Kaji Lin Ka Mosques: A Tale of Two Community Spaces

The Kaji Lin Ka Mosque is a notable religious and cultural establishment in Lhasa, comprising two distinct buildings that embody the intersection of Tibetan and Islamic architectural styles. The history of these mosques is intricately linked to a legend involving a Kashmiri mullah who emigrated to Tibet. This tale is not merely a narrative but rather a foundational myth that signifies the beginning of a harmonious coexistence between Islamic and Tibetan cultures in the region. The mullah is said to have been welcomed by the local Tibetan community, which set the stage for the construction of the mosques, thereby creating a vital communal space that still serves as a center for worship and social interaction today.

Architecturally, the two mosques illustrate a fascinating amalgamation of design elements borrowed from both Islamic and Tibetan traditions. The Kaji Lin Ka Mosque features traditional minarets and domes typical of Islamic structures, yet these elements are harmoniously blended with Tibetan motifs and colors, creating a unique aesthetic that reflects the cultural convergence of the region. The vibrant prayer halls are adorned with intricate woodwork and local artwork, further emphasizing the collaboration between artisan techniques and religious expressions.

The community role of the Kaji Lin Ka Mosques extends beyond mere worship; they function as sites for gathering, education, and cultural exchange. Regular Islamic prayers, community celebrations, and cultural events are held here, promoting a spirit of fellowship among the diverse community members that frequent these spaces. The mosques stand as a testament to a rich history of tolerance, recognizing the importance of shared spaces in maintaining cultural heritage while fostering mutual respect and understanding. This harmonious blend of traditions positions the Kaji Lin Ka Mosques not only as places of faith but also as crucial pillars supporting the vibrant cultural tapestry of Lhasa.

Raosai Lane Mosque: The Small but Significant Structure

The Raosai Lane Mosque, an often-overlooked edifice in Lhasa, plays a significant role in the confluence of various cultures on the Roof of the World. This mosque has a rich historical background dating back to the early 20th century, serving as a spiritual haven for Muslim merchants and travelers who traverse the region. Its establishment marked the introduction of Islamic architectural elements into the sociocultural fabric of Lhasa, contributing to the city’s diverse religious landscape.

Architecturally, the Raosai Lane Mosque stands out due to its unique blend of traditional Tibetan style and Kashmiri influences. This amalgamation is evident in its ornate wooden carvings, intricate plasterwork, and vibrant colored tiles, which showcase the harmonious coexistence of distinct cultural identities. The mosque is modest in size, ensuring an intimate atmosphere that fosters community engagement. Despite its small stature, it serves as a focal point for local Muslims, hosting prayers and gatherings that reinforce social bonds.

The mosque’s location on Raosai Lane is strategic, serving not only the immediate community but also functioning as a welcoming space for transient visitors and merchants seeking respite. This accessibility allows the mosque to play a crucial role in the daily lives of those who frequent it. It facilitates the exchange of ideas and traditions, further enriching the cultural tapestry of Lhasa. The atmosphere is characterized by a sense of unity among its attendees, transcending cultural and ethnic boundaries. Through its architectural charm and communal function, the Raosai Lane Mosque stands as a testament to the harmonious coexistence of cultures in Lhasa.

Duodi Mosque: A Cornerstone of Annual Celebration

Duodi Mosque, strategically situated close to the Muslim cemetery in Lhasa, stands as a prominent establishment within the city’s rich tapestry of cultural diversity. This mosque is not only a place of worship but also serves as a pivotal hub for the annual ‘Zhuan Fan Jie’ or Pilaf Festival, which celebrates the unique culinary traditions of the Muslim community in this region. As an epicenter of cultural unity, the mosque plays a vital role in fostering community spirit and celebrating local heritage.

Each year, the mosque becomes a gathering point for Lhasa’s Muslim populace, who come together to honor this vibrant festival, showcasing the importance of culinary arts as a medium of cultural expression. The atmosphere during this festival is filled with joy and camaraderie, as attendees participate in the preparation and sharing of traditional pilaf dishes. This communal effort not only reinforces social bonds among locals but also highlights the significance of food in cultural identity and communal harmony.

The Duodi Mosque also encourages participation from various segments of society, inviting individuals of diverse backgrounds to partake in the festivities. This inclusiveness exemplifies the mosque’s role in bridging cultural divides, as it creates an environment where culinary traditions can be appreciated through the lens of shared experiences. Aimed at not just preserving Islamic heritage, the mosque and its annual celebrations contribute significantly to the larger cultural narrative of Lhasa, positioning itself as an essential component of the city’s social fabric.

In this way, the Duodi Mosque not only fulfills its religious obligations but also serves as a cornerstone for annual celebrations, reinforcing cultural unity within Lhasa’s Muslim community while simultaneously inviting broader participation from the regions’ diverse population.

Cultural Synthesis: Unique Practices in Lhasa’s Mosques

Lhasa, known as the Roof of the World, serves as an extraordinary backdrop for the harmonious blending of Tibetan and Islamic cultures, particularly evident in its mosques. The architectural style of these mosques showcases a remarkable synthesis, where traditional Islamic elements complement Tibetan design motifs. The use of intricate wood carvings, vivid frescoes, and colorful prayer flags transforms these religious spaces, allowing them to resonate with both faiths. The melding of pagoda-like structures with the classic minaret is illustrative of the cultural dialogue between Tibetan and Islamic traditions.

Moreover, the integration of languages in worship and education further exemplifies this cultural synthesis. In Lhasa’s mosques, bilingual practices prevail, with prayers often recited in both Tibetan and Arabic. This duality not only facilitates an inclusive environment for worshippers but also underscores the shared spiritual heritage. The presence of multilingual educational programs for children demonstrates an effort to foster understanding and respect among various cultural groups. In these programs, religious teachings are conveyed in Tibetan, Arabic, and Mandarin, creating an enriching learning experience that embraces linguistic diversity.

The community events organized in Lhasa’s mosques also reflect this unique blending of cultures. During significant Islamic holidays, Tibetan customs are incorporated into celebrations, creating a vibrant tapestry of shared values and practices. The preparation of traditional foods, which may combine elements from both Tibetan and Islamic culinary traditions, exemplifies the creative fusion that emerges from this cultural intermingling. Such events not only strengthen bonds within the community but also invite dialogue between different faith groups, fostering a deeper appreciation of each culture’s unique contributions.

The Pilaf Festival: A Symbol of Unity

The Pilaf Festival, an annual celebration in Lhasa, stands as a vibrant emblem of the harmonious coexistence of Tibetan and Hui cultures. This festivity not only offers a platform for showcasing the intricacies of these rich traditions but also serves as a unifying force for the diverse communities residing in this historical city. Held during the harvest season, the festival primarily revolves around the preparation and sharing of pilaf, a dish highly regarded for its cultural significance across both ethnic groups.

Localized Community Life: The Tibetan-Hui Connection

The Hui community in Lhasa represents a unique confluence of cultures, deeply rooted in both Tibetan traditions and Islamic heritage. Occupying a distinct space within the broader tapestry of Tibetan society, the Hui have adapted their customs while sharing their rich cultural heritage, contributing significantly to the local economy and community life. Predominantly engaged in trade, the Hui people run various businesses, including restaurants, shops, and markets, which serve both the local population and visiting tourists. This economic interdependence has fostered not only livelihoods but also friendships, creating a familiar atmosphere among different ethnic groups.

Cultural practices among the Hui in Lhasa reflect a harmonious blend of their Islamic faith and Tibetan lifestyle. Community events, festivals, and daily interactions showcase this synthesis, where traditional Chinese Muslim customs are observed alongside Tibetan practices. For instance, during religious holidays, Hui families engage in communal prayers and festive meals, often inviting their Tibetan neighbors to join them, reinforcing bonds of friendship and cooperation. The mutual respect exhibited by both groups over generations highlights their shared history and the importance of community solidarity.

Hui Community in Lhasa

The Hui community’s commitment to promoting inter-ethnic unity can be observed in their advocacy for communal activities that embrace diversity. Initiatives such as cultural exchange programs, collaborative festivals, and joint charitable events provide platforms for residents to learn from one another, dissolving misconceptions and building trust. These endeavors illustrate that the Hui and Tibetan populations can coexist peacefully, with a shared vision for a harmonious society. The local government’s support for such initiatives further cements this integration, recognizing the Hui community as integral to Lhasa’s identity and future.

In this context, the Tibetan-Hui connection is not merely a societal interaction but a continually evolving relationship that mirrors the dynamic and complex nature of life in one of the highest cities in the world.

Conclusion: Embracing Unity Without Uniformity

The cultural tapestry of Lhasa, often referred to as the Roof of the World, exemplifies the intricate interplay of diverse traditions and religions. The great mosques of this unique city stand not merely as places of worship but as embodiments of harmony and coexistence among varied communities. As Lhasa hosts a multitude of faiths, including Tibetan Buddhism, Islam, and others, these mosques reveal a profound message: unity can flourish amid diversity.

Each mosque, with its architectural beauty and spiritual significance, invites individuals from varying backgrounds to come together. They embody a truth that transcends mere tolerance; they promote mutual respect and understanding among the followers of different religions. While the architectural styles may differ, and the theological tenets may vary, what remains poignant is the shared reverence for the essence of faith itself. The mosques facilitate dialogues that enhance community bonds and encourage intercultural exchanges, becoming centers where stories of individual struggles and triumphs are shared and appreciated.

This spirit of inclusion is particularly significant in today’s increasingly polarized world. By embracing the principle of “unity without uniformity,” Lhasa’s religious sites illustrate that cultural differences can strengthen rather than weaken our social fabric. The mosques are, therefore, more than just religious landmarks; they are a testament to the resilience of human connections amidst diversity. They remind us that celebrating differences does not diminish our common humanity but rather enriches it, paving the way for a more inclusive and harmonious society.

In conclusion, Lhasa’s great mosques are not merely structures of worship but pivotal instruments in fostering a culture of acceptance, respect, and unity among the city’s diverse residents. The essence of “unity without uniformity” resonates deeply within these sacred spaces, inspiring future generations to appreciate and celebrate the richness of cultural diversity in their midst.

Historical Roots and Conservation Status

Historical Origins

- Earliest Records: The 10th-century work Hudud al-‘Alam (The Regions of the World) first mentioned a mosque and a small Muslim presence in Lhasa.

- Community Formation: By the 17th century, Muslims from Kashmir and inland China began to settle in Lhasa, forming two main groups:

- Hebalin Mosque: Descendants of inland Hui, often engaged in butchery and catering.

- Rabsael Lane Mosque: Descendants of Kashmiri and Ladakhi groups, primarily involved in trade.

- Designated Area: The Fifth Dalai Lama’s “arrow shot” designated Kaji Linka as an exclusive community, which includes the mosque, residences, and the vast 64,000-square-meter Muslim cemetery. The cemetery holds 23 preserved gravestones, the earliest dating back to the Qianlong period of the Qing Dynasty, marking centuries of history.

Status and Protection

All four mosques are currently designated as Lhasa Municipal Cultural Heritage Sites and undergo regular maintenance. Each mosque has a democratic management committee, inheriting the traditional “election every three years” system for daily administration and religious activities. The Lhasa Muslim community has achieved significant improvements in livelihood and well-being in recent years.

Lhasa’s four mosques serve as a unique testimony to Islamic culture on the roof of the world. They are more than just places of worship; they are a crystallization of Tibetan-Hui cultural synthesis. From architectural style to religious ritual, and from folk customs to community life, they embody the wisdom of cultural co-existence and are a vivid microcosm of harmonious multiculturalism in Tibet.