Tibetan Empire Clothing: Highland Fur

The clothing of the Tibetan Empire tells a powerful story of Tibet’s early history. It began with wind-beaten fur and thick wool on the high plateau, later absorbed luxurious silk influences from the Tang, Tazig and Kashmir. It eventually became a visual language of status, courage, and spiritual belief.

More than simple garments, Tibetan Empire clothing expressed identity. What people wore could show their rank, bravery in battle, and even divine protection. Let’s travel back over a thousand years to explore what people in the Tibet Empire wore — and why it mattered.

Clothing in the Tibetan Empire (618–842 CE):

The Tibetan Empire (7th–9th centuries) was one of the most powerful empire in Inner Asia. At its height, it controlled vast stretches of Central Asia and key sections of the Silk Road. Clothing during this era reflected three defining realities:

- The harsh high-altitude climate

- A highly stratified political system

- Active trade and cultural exchange across Eurasia

Although direct archaeological evidence is limited, murals, textiles, inscriptions, and tomb discoveries help us reconstruct what people wore during the imperial period.

Royal Dress and Symbols of Rank

Before the reign of Songtsen Gampo reshaped Tibetan politics and culture, clothing in Tibet society was practical and suited to the harsh plateau climate. Historical sources describe both nobles and commoners wearing braided hair and heavy felt or fur garments. Warmth came first.

But as Tibetan Empire grew into a powerful empire, royal clothing developed distinct symbolic forms.

Tazig Influence on Early Tibetan Court Dress

Certain garments described in Tibetan records resemble West and Central Asian styles:

- Red ceremonial headgear worn by early Tibetan rulers

- Long robes with structured tailoring

- Upturned boots, similar to Central Asian riding footwear

Traditions associated with Songtsen Gampo describe him wearing a tall red hat, sometimes interpreted as having parallels with West Asian or Central Asian ceremonial forms.

Additionally, some robe styles mentioned in Tibetan texts appear distinct from early Chinese dress traditions, suggesting that imperial Tibetan attire was shaped by multiple cultural currents rather than a single source.

Tibet fashion, therefore, should be understood as part of a wider Inner Asian exchange network that included Persia, Kashmir, India, China and Silk Road polities.

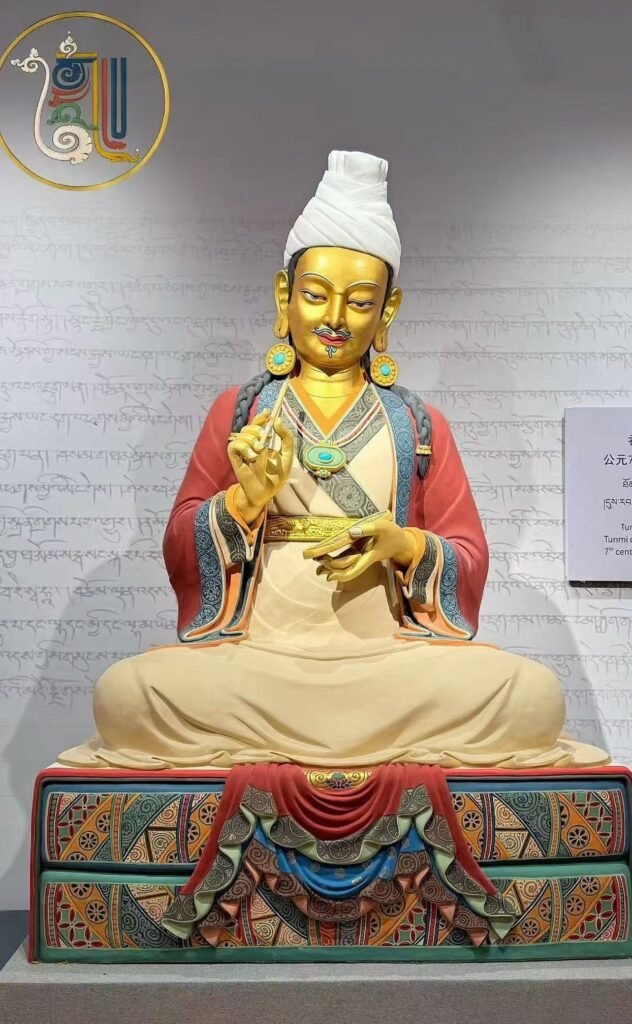

The Two Royal Images of Songtsen Gampo

During the 7th century, the Tibet Tsenpo king became associated with two iconic styles.

1. The Indigenous Tibet Royal Attire

One traditional image features a tall red ceremonial hat known as “Tsensha.” The pointed hat was wrapped with red silk, and according to Tibetan religious tradition, it sometimes symbolically contained an image of Amitayus (Buddha of Infinite Life). Long silk ribbons crossed over the chest, forming a dignified and sacred appearance.

Some ancient statues in Tibetan temples — including depictions preserved at the Potala Palace — still reflect this style. The image represents a fusion of kingship and spiritual authority, a theme central to early Tibetan state formation.

The Red Warrior Hat Tradition

In western Tibet, particularly in the region of Ngari and Ladakh, certain lineages traditionally associated with ancient royal descent have preserved ceremonial garments said to resemble early imperial attire.

During festivals such as Losar (Tibetan New Year), some families wear:

- A tall, narrow red hat shaped like an ancient warrior’s crown

- A pointed top wrapped with red silk

- A small image of Amitayus (Buddha of Infinite Life) tied near the upper edge

- Long red silk ribbons crossed over the chest

This style strongly resembles early depictions of imperial Tibetan kings in temple statues, including those associated with the Potala Palace.

The red warrior hat, sometimes described as a btsan zhwa (warrior hat), embodies a blend of martial authority and sacred symbolism. The inclusion of Amitayus imagery reflects the fusion of royal power and Buddhist devotion that characterized later interpretations of early Tibetan kingship.

2. The Silk-Influenced Court Dress

The second royal image emerged after Tibet entered deeper diplomatic and cultural exchange with the Neighboring Kingdoms. Historical accounts record that after encountering the refined dress of Tang envoys, the Tibetan court began adopting silk and brocade garments.

When examining Tibetan imperial dress, it becomes clear that it developed through layered influences:

- Indigenous plateau traditions

- West and Central Asian (Tazig/Persian) elements

- Indian and Kashmiri aesthetics

- Tang-era Silk Road exchange

Rather than replacing local identity, foreign elements were absorbed and reinterpreted within a Tibetan cultural framework.

The red hat tradition, structured robes, and upturned boots all suggest a society positioned at the crossroads of Inner Asia — confident enough to adopt and transform outside influences while maintaining its own spiritual and political symbolism. The change symbolized not submission, but imperial sophistication and participation in the wider Silk Road world.

General Styles: The Foundation of Tibetan Dress

The core garment of the Tibetan Empire was a long, loose robe — the ancestor of today’s chuba (chupa). Its essential features already appeared during imperial times.

Key Characteristics

- Wide waist and long sleeves: Sleeves often extended beyond the hands for warmth. They could be rolled up or even used as storage pockets.

- Open front design: Secured with belts or sashes, allowing flexibility. In warmer weather, one sleeve might be worn off the shoulder.

- Ankle-length cut: Suitable for both men and women, with variations depending on labor, travel, or ceremony.

The design prioritized mobility — crucial for herding, horseback riding, farming, and warfare.

Royal Attire in Iconography: The “Tang Zho” Garment

Some depictions of kings and protective deities such as Dorje Legpa show them wearing a garment referred to in Tibetan sources as “Tang Zho” (thang zhu).

This robe appears to be:

- Structured and formal

- Associated with royal or divine authority

- Distinctive in cut compared to later Tibetan monastic dress

Unlike many imported styles, this garment is described in Tibetan sources as indigenous rather than foreign. Interestingly, similar robe forms are seen in early Himalayan regions east of India, including historical Burma (Myanmar), whose royal chronicles trace ancestral links to Tibetan lineages in certain traditions.

If these connections hold historical weight, it raises the possibility that Tibetan imperial rulers may at times have worn the Tang Zho as a ceremonial garment.

Red as a Royal and Warrior Color

Across descriptions of early Tibetan rulers (btsan and btsanpo), a striking pattern emerges:

- Red warrior hats

- Rudar- Red banners

- Phodrang Marpo -Red fortresses

- Red ritual headgear

The color red symbolized power, protection, vitality, and sovereignty. It also resonated with the fierce protective deities of Tibetan cosmology.

This visual unity — red garments, red architectural elements, red military insignia — may have created a coherent imperial identity. Clothing, banners, fortresses, and ritual objects worked together to project authority.

Clothing as a System of Political Identity

The Tibet state developed a structured ranking system in which clothing and ornaments clearly marked official status.

This system, sometimes described as a form of official insignia, distinguished rank through material:

- Highest Rank: Gemstone insignia (including etched agate), awarded to top ministers such as the chief minister.

- Middle Rank: Gold or gold-and-silver insignia for high officials.

- Lower Rank: Bronze or iron insignia for lower administrative officers.

Military bravery was also honored visually. Warriors who distinguished themselves could receive special decorations, including robes trimmed with tiger or leopard skins. Clothing functioned as both reward and recognition.

In Tibet society, dress was governance made visible.

From Felt Robes to Silk Brocade

The introduction of silk into Tibet did not replace traditional wool overnight. Instead, it layered new meaning onto existing traditions.

Following diplomatic marriages and exchanges between Tibetan Empire and the Tang court, silk textiles became highly valued among Tibetan elites. Silk garments, brocades, and embroidered fabrics entered royal and aristocratic wardrobes.

However, Tibet’s high-altitude climate remained unforgiving. Silk alone could not provide sufficient warmth. As a result:

- Silk was often used as decorative trim on collars and sleeves.

- It served as ceremonial dress rather than daily wear.

- It became a prestigious diplomatic gift.

Silk symbolized wealth and connection to powerful neighboring civilizations, but it did not displace traditional materials.

The Enduring Power of Pulu (Tibetan Wool)

Despite the rise of silk fashion among elites, traditional Tibetan wool — known as pulu — remained essential.

A high-quality pulu robe could last a lifetime. Its design was practical and adaptable:

- Tied during the day as a robe.

- Loosened at night to serve as bedding.

- Sleeves could be slipped off in warm weather.

- Both sleeves could be removed during heavy labor.

Even royal garments associated with Songtsen Gampo were made from fine pulu wool, showing that functionality and tradition endured at every level of society.

The classic Tibetan robe (chuba) that evolved from these early designs remains one of the most recognizable symbols of Tibetan culture today.

Clothing as Climate, Culture, and Cosmology

Tibet clothing was never just fashion. It reflected:

- Climate: Survival in a high-altitude environment.

- Politics: Rank and imperial authority.

- Military Culture: Public recognition of courage.

- Religion: Integration of sacred imagery into royal symbolism.

- Trade Networks: Participation in Silk Road exchanges.

From fur-lined felt to silk-trimmed robes, the Tibet Empire’s clothing history mirrors the transformation of Tibet itself — from a rugged highland kingdom to a cosmopolitan empire woven into the fabric of Inner Asia.

Turquoise: Divine Embodiment and Proof of Courage

If silk symbolized prestige and international exchange, turquoise — known in Tibetan culture as one of the most sacred gemstones — represented something far deeper. It was believed to embody divine presence and spiritual protection.

In the Tibet Empire era, turquoise was not merely decorative. It carried layered meanings tied to religion, authority, gender identity, and social order.

Turquoise as Sacred Power

Turquoise (green-blue stone) has long been treasured across the Tibetan Plateau. Its sky-blue to blue-green color was associated with heaven, vitality, and protection.

Spiritual and Political Symbolism

- Sacred Ornamentation: Turquoise was widely used in decorating sacred statues and ritual objects in early Tibetan Buddhist contexts.

- Rank and Authority: It also appeared in official dress as a marker of status.

- Oath and Alliance: During the reign of Songtsen Gampo, turquoise was reportedly used in important oath ceremonies, symbolizing sincerity and divine witness.

To wear turquoise was to carry both social legitimacy and spiritual blessing.

Protection for Men and Women

Turquoise also carried gender-specific symbolism in Tibet Empire society:

- Men’s Earrings: Turquoise earrings worn by men were associated with bravery and masculine protection. They were believed to attract the blessing of protective male deities and affirm courage.

- Women’s Headdresses: Women wore turquoise on elaborate head ornaments, symbolizing beauty, prosperity, and family wealth.

This tradition of valuing turquoise has continued for centuries. Even today, turquoise remains one of the most recognizable symbols of Tibetan identity and aesthetics.

Soldiers and Commoners: Practical Daily Wear

Despite the rich symbolism in elite dress, everyday clothing during the Tibet Empire remained highly practical.

Military attire differed little from civilian clothing. Soldiers typically wore:

- A traditional Tibetan long robe (early form of the chuba).

- An outer vest made of pulu wool or sheepskin.

- A wrapped headscarf.

- Armor added only during combat.

This practicality reflects the realities of life on the plateau, where survival often mattered more than display.

Archaeological Discoveries from Dulan

Recent archaeological excavations in Dulan County, Qinghai, have provided rare insights into Tubo-era clothing.

In Tubo-period tombs in the Dulan region, researchers uncovered remarkably preserved garments, including:

- A brown round-collar short jacket.

- Yellow striped trousers with a closed crotch design.

- Black knee-high pointed boots.

What makes this discovery particularly fascinating is its multicultural blend:

- The jacket shows stylistic features similar to Tang-era robes.

- The trousers reflect Persian textile influences.

- The boots resemble Central Asian nomadic styles.

These findings demonstrate that the Tibet Empire was not isolated. Instead, it stood at a crossroads of Inner Asian exchange, absorbing and adapting diverse cultural elements into its own distinctive identity.

The Deeper Meaning Behind Tibet Empire Clothing

Looking back at the evolution of Tibet Empire clothing reveals more than a story of protection against cold weather.

Practicality as Foundation

No matter how styles evolved, adaptation to the plateau’s harsh climate remained the core principle. The pulu robe’s flexibility and durability made it indispensable.

Silk as Cultural Bridge

Silk flowing along ancient trade routes connected Tibet with powerful neighboring civilizations. It was not only luxurious fabric but also a medium of diplomacy, exchange, and prestige.

Gemstones as Spiritual Soul

Turquoise shone as a reflection of Tibetan Empire spiritual values — reverence for divine forces, admiration for courage, and respect for social order.

From rugged highland wool to silk-trimmed ceremonial robes, and from protective turquoise to cross-cultural garments revealed by archaeology, Tibetan Empire clothing became more than attire. It evolved into a wearable chronicle — an epic woven in wool, silk, and stone across the roof of the world.