Tibetan monasteries are places that teach about kindness and gentle behavior. But when you visit one, it feels quite different. The word for “monastery” in Tibetan, called Gonpa “དགོན་པ”, has a special meaning that constantly shows itself, being on the edge of everyday life.

Inside these spiritual places, you’ll find dim lights, monks in crimson robes, lingering incense, and chanting sounds. Even scary-looking guardian deities are there, creating a mysterious and holy space. In this space, there’s a serious feeling, as if looking coldly at the normal world.

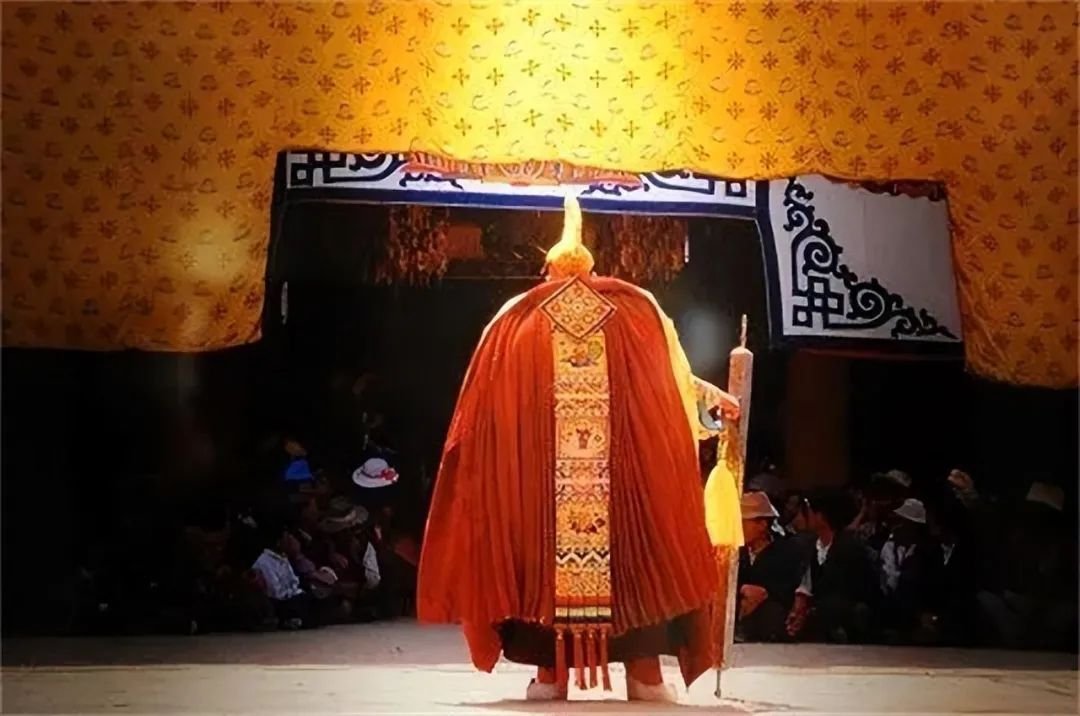

In this holy space, there’s a person who represents all this seriousness. Dressed in a heavy crimson cloak and holding a square iron rod, this person is called the Iron Rod Monk (Gekoe). They walk among the rows of monks, hitting the iron rod on the ground with each step, making a clear sound that shows how strict the monastery rules are. This important person is actually the Monastic Disciplinary Officer—the Iron Rod Monk (Gekoe).

The Role and Etymology of “Gekoe” in Tibetan Buddhism

Commonly referred to as “Gekoe”, in Tibetan (དགེ་སྐོས/དགེ་བསྐོས) or “Shalngo” (ཞལ་ངོ), with an alternative term “Choetrimba” (ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་པ). This can be translated as “Disciplinarian” (དགེ་བ་ལ་བསྐོས་པ), also translates to “Law Enforcer.” According to the research conducted by Berthe Jansen from Leiden University, the term is a transliteration of the Sanskrit word “upadhivārika,” found in Buddhist Vinaya literature, meaning “administrator.”

In the Vinaya, this position is defined by Buddha himself, outlining the responsibilities, including sweeping dust off seats. Additionally, Japanese scholar Takeuchi, analyzing a Dunhuang manuscript (Pt.1119, housed in the National Library of France), discovered that Gekoe was also responsible for borrowing and lending grains from the monastery’s granary. The document featured two seals—one representing the borrower and the other likely belonging to the Gekoe at the time. This connection between the term “Gekoe” and the disciplinary role in Buddhism appears to have developed later.

The term “Gekoe” thus encompasses the multifaceted responsibilities of managing discipline, including both physical cleanliness and economic affairs within the monastery, reflecting the intricate role played by these figures in Tibetan Buddhist institutions.

The Enigmatic Law Enforcer – Iron Rod Monk

In this sacred realm, there exists a figure embodying authority. Adorned in a heavy crimson cloak and wielding a square iron rod, this figure, known as the “Gekoe” (དགེ་སྐོས/དགེ་བསྐོས) or “Shalngo” (ཞལ་ངོ) in Tibetan, is often referred to colloquially as the Iron Rod Monk.

Chayik – The Ancient Rules of Tibetan Monasteries

In Tibetan, “Chayik” (བཅའ་ཡིག) refers to the set of regulations governing the monastic life within a temple. In the earliest collection of “Chayik” the term “Gekoe” wasn’t used. Instead, different words were employed to signify those responsible for maintaining discipline in the monastery, such as “Panniva” (བན་གཉེར་བ), literally translating to “supervisor of monks.”

One renowned monastery with a long history is the Drigong Thil Temple (འབྲི་གུང་མཐིལ) in the Tibetan region. In one set of “Chayik” rules from this temple, a clear instruction is given: “Panniva, you must encourage new monks to study scriptures and rules.” The author of these rules is believed to be Chenya Drakpa Jungney Jangney (སྤྱན་སྔ་གྲགས་པ་འབྱུང་གནས། 1175-1255), who served as the fourth abbot of Drigong thil Temple from 1235 to 1255. Therefore, these regulations likely date back to that period. Based on this evidence, Berthe Jansen suggests that the term “Gekoe” as a disciplinary figure emerged after the 15th century.

The Integral Role of Gekoe in Tibetan Monastery Disciplinary Affairs

Architect of Monastic Rules

Gekoe, the disciplinarian of monasteries, plays a crucial role not only in enforcing rules but also in the formulation of monastery regulations. Their responsibilities extend to reciting these rules, known as “Chayik” in specific ceremonies and occasions. Taking the example of kerti Monastery (ཀིརྟི་དགོན), the monastery schedules two sessions annually for the chanting of rules during its eight-course curriculum.

The Exemplary Gekoe of Jokhang Temple

During special events, such as the Lhasa Prayer Festival (ལྷ་སའི་སྨོན་ལམ་ཆེན་མོ), the disciplinarians of Jokhang Temple, known as “Drepung Tsokchen Shalngo” (འབྲས་སྤུངས་ཚོགས་ཆེན་ཞལ་ངོ), march through the streets carrying the monastery’s Chayik on their shoulders.

The Mythical Origin of Drepung Monastery’s Gekoe

Legend has it that when Jampal Gyatso, a direct disciple of Tsongkhapa (རྗེ་ཙོང་ཁ་པ། 1357-1409), established Drepung Monastery, it had only eight monks. Witnessing a chaotic incident during a routine ceremony where one monk was injured, Jampa Gyatso proclaimed it as an auspicious sign. He predicted that countless Buddhists would flock to the monastery. Immediately, he appointed a Gekoe to oversee discipline, and the iron rod used by the Gekoe is preserved in the Jamyang Institute within Drepng Monastery.

The Elaborate Election of Drepung monastery Gekoe

The election process for the disciplinarian in Drepung Monastery is intricate. Starting in the Tibetan month of June, two Gekoe are elected through a meticulous process. The ten specific departments of Drepung each nominate a candidate for the initial selection. After the preliminary round, all candidates must travel to Norbulingka (ནོར་བུ་གླིང་ག) for the final examination by June 15th in the Tibetan calendar. Results are communicated by two messengers (ཐབ་གཡོག), and the selected candidates treat them with yogurt and ginseng fruits as a sign of good fortune. The messengers then determine the roles of primary and assistant Gekoe based on their qualifications.

Responsibilities during Celebrations and Ceremonies

Starting from the Tibetan month of June 29th, during the Shoton Festival, Drepung Monastery organizes Tibetan opera performances in front of the Powa Langri (ཕོ་བ་གླང་རི) staircase. Both outgoing and incoming Gekoe are required to attend. On June 30th, during the giant Thangka sunning ceremony, a formal inauguration is held for the new Gekoe. As part of the festivities, the new Gekoe leads the procession returning the Thangka to the main hall, marking their official entry into the role. Notably, as the new Gekoe ascends the ceremonial seat, the outgoing Gekoe proceeds cautiously, wary of potential reprisals from previously offended monks during their tenure.

The Distinguished Attire and Responsibilities of Gekoe in Tibetan Monasteries

Gekoe, distinguished from ordinary monks, wear a unique ensemble designed to accentuate the strictness of the monastic code and the authority of their role. Adorned in crimson-colored woolen monk robes, they wear a red and yellow silk vest underneath, covered by a Khachu, and adorned with a foot-long shoulder pad called “Apo” (ཨ་འབོག). Completing the outfit are high-quality monk skirts, big boots, and a pointed high hat. During major gatherings, Gekoe Head, a crimson cloak with intricately embroidered long strips, a golden Gawu box necklace, and wield iron rods with gold borders, slowly and heavily patrolling the main hall.

Duties Beyond Discipline

The primary responsibility of Gekoe is to oversee daily discipline, ensuring the appropriateness of monks’ attire and their civilized behavior. In the past, Drepung Monastery Tsokchen Shalngo also handled tax collection. As there were small businesses within the monastery, Gekoe would collect taxes from them. While specific tax rates are unknown, historical records mention taxing one Sang (Tibetan Dollar). During the winter ritual festival, Gekoe faced additional duties related to customary offerings, leading to increased tax collections. Despite the fluctuating annual tax revenue, Gekoe managed to secure substantial income through these efforts.

Arbiters rule of Gekoe

Gekoe play a crucial role in settling disputes within the monastery, guided by the principles of monastic rules. These rules also demand that Gekoe maintain impartiality and strictness. For instance, in the Rule book of the Monastery, it states that if an administrator’s negligence allows wrongdoers to escape justice, the administrator must bow five hundred times as a punishment. Similarly, if a disciplinarian’s oversight leads to issues, the disciplinarian must bow a thousand times as a penalty.

Stern Rebuke and Constant Vigilance

A stern rebuke letter from the thirteenth-century addressed to two Gekoe underscores the need for vigilance. The letter criticizes their negligence, warning of dire consequences if they don’t immediately rectify their behavior. It highlights the importance of upholding the rigorous monastic code, emphasizing that the well-being of sentient beings depends on the strict adherence to the code. The letter serves as a reminder that even the formidable Iron Rod Monks must maintain reverence and vigilance to protect the monastery and its inhabitants.

In conclusion, Gekoe in Tibetan monasteries don distinctive attire, undertake diverse responsibilities beyond discipline enforcement, and serve as arbitrators in controversies, ensuring the sanctity and adherence to monastic rules. Their authority and vigilance are integral to preserving the sanctity and order within the monastery.