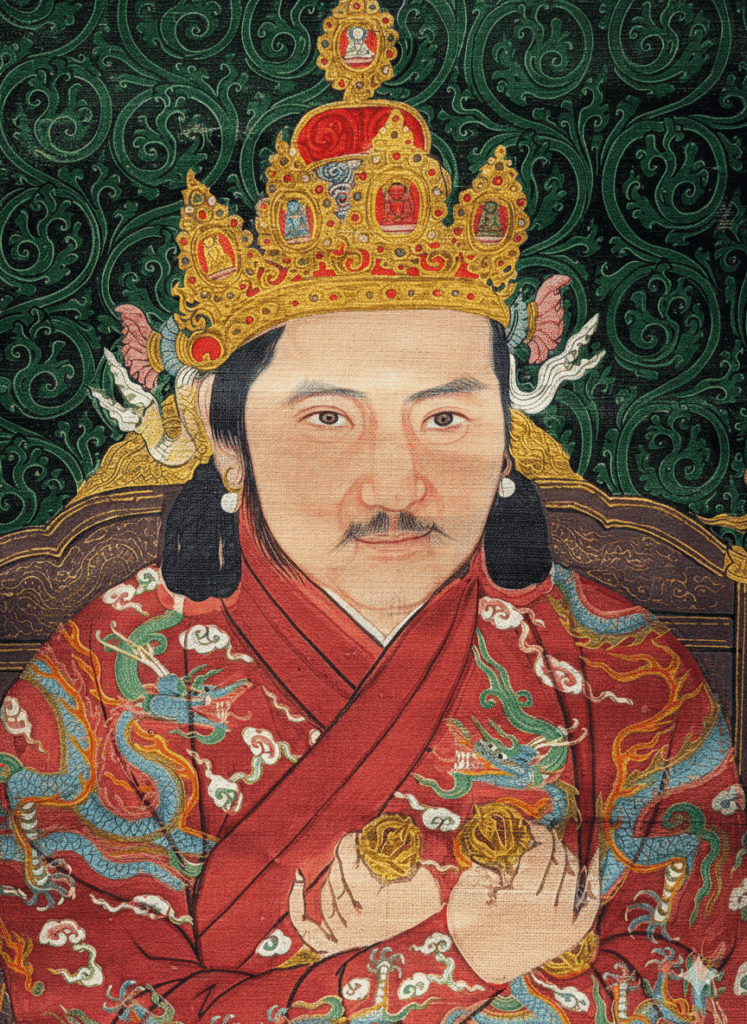

Tugh Temur (1304–1332), Mongolian: ᠲᠦᠪᠲᠡᠮᠦ known posthumously as Emperor Wenzong of the Yuan dynasty, was one of the most politically active rulers of the Mongol Empire’s later period. Bearing the Mongolian khan title Jayaγatu Khan, he became the eighth emperor of the dynasty and ruled twice—first from 1328 to 1329, and again from 1329 until his death in 1332.

Although his reign lasted only about five years, it marked a critical phase in consolidating imperial authority and strengthening ties with Tibetan Buddhism—an alliance that played a decisive role in legitimizing Mongol rule over vast multicultural territories.

A Violent Struggle for the Throne

Following the death of Yesun Temur in 1328, the Yuan court plunged into a fierce succession crisis. The powerful minister El Temur installed Tugh Temur on the throne in Dadu (modern Beijing), while rival elites in Shangdu supported the late emperor’s son, Ragibagh.

This confrontation triggered the famous War of the Two Capitals, a decisive conflict that ultimately ended with Tugh Temur’s victory and the temporary stabilization of the empire.

Earlier, Jayaatu Khan Tugh Temür had pledged to yield the throne once his elder brother Kusala returned. True to his word, he abdicated in 1329 when Kusala was proclaimed emperor in the northern steppes. However, Kusala died suddenly on his journey south—an event many historical sources attribute to poisoning orchestrated by Tugh Temur and El Temur. Soon afterward, Tugh Temur reclaimed the throne.

Strengthening Central Authority

During his reign, Emperor Wenzong pursued an assertive political strategy:

- Suppressing rival factions

- Expanding centralized governance

- Quelling rebellions in Sichuan and Yunnan

- Reinforcing imperial oversight across frontier regions

One of his most consequential policies was maintaining the Yuan administrative system in Tibet. Through the Bureau of Buddhist and Tibetan Affairs (Xuanzheng Yuan), the court preserved a religious-political alliance with the Sakya school—continuing a governance model first institutionalized under Kublai Khan.

Institutionalizing the “Rule Through Clergy” Model

Building upon earlier precedent, Emperor Wenzong further refined the imperial strategy often described as “governing Tibet through Buddhist hierarchs.” Tibetan Buddhism became not only a spiritual resource but also a pillar supporting imperial legitimacy.

He reaffirmed the position of Imperial Preceptor by appointing Kunga Legpai Jungne, a prominent figure from the influential Khön family and a descendant of Drogön Chögyal Phagpa. The practice of retaining a previous emperor’s preceptor after a new ruler ascended soon became court convention.

In 1329, the emperor elevated another high lama, Rinchen Gyaltsen, creating the rare situation of two Imperial Preceptors simultaneously—one overseeing the Xuanzheng Yuan and the other directing Buddhist rituals within the palace.

Opening the Court to Multiple Tibetan Traditions

A landmark moment came in 1331 when imperial envoys were dispatched to invite Rangjung Dorje, the third reincarnate lama of the Karma Kagyu tradition, to the imperial capital.

There, he performed initiations, conducted memorial rites for the royal family, and offered tantric teachings. This invitation broke new ground—until then, the Sakya hierarchy had dominated court influence. By welcoming a non-Sakya master, Emperor Wenzong broadened political engagement with diverse Tibetan schools.

The move subtly expanded Yuan authority by integrating multiple religious networks into the imperial orbit.

A Wave of Tibetan Buddhist Architecture and Art

Imperial patronage extended beyond titles and ceremonies. The court sponsored the construction of numerous Tibetan-style temples, including the Dachengtian Husheng Temple and Dachong’en Fuyuan Temple, reportedly part of a broader program that established twelve major monasteries.

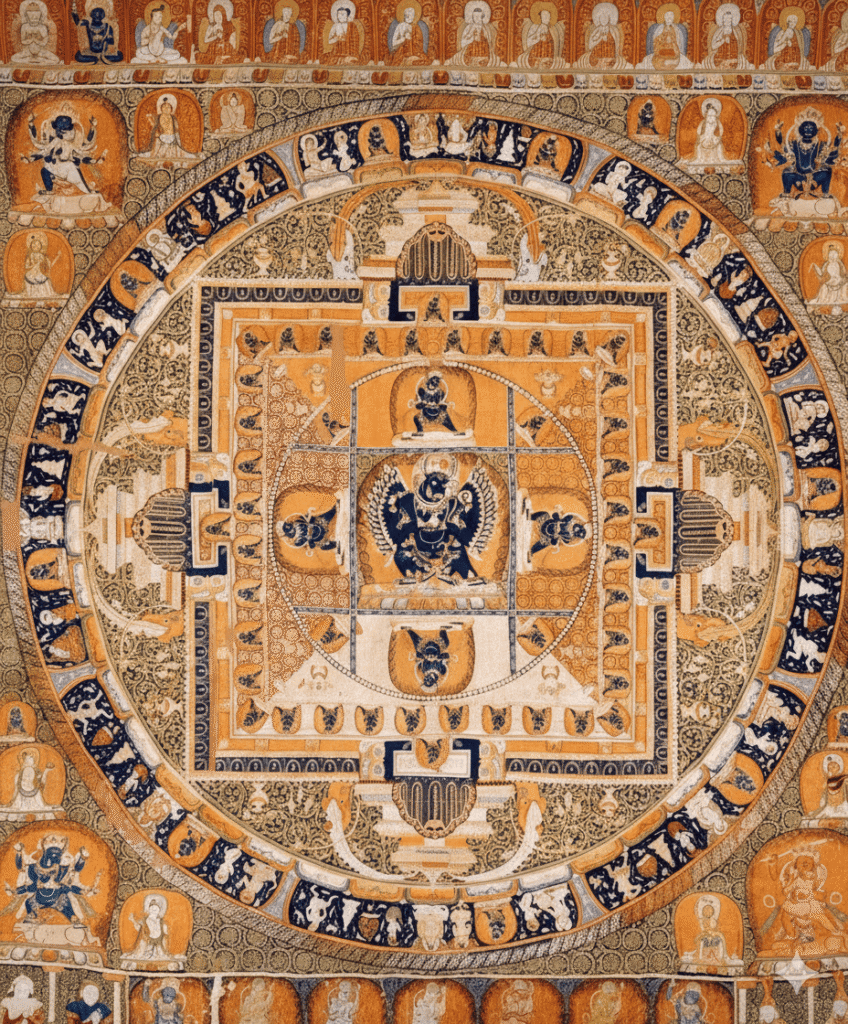

To support this flourishing religious culture, the government created specialized artisan bureaus responsible for crafting Buddhist statues and ritual objects. This initiative gave rise to a distinctive artistic movement sometimes called the “Western Heaven Brahmanic Style,” which helped Tibetan Buddhist imagery spread widely across inner China.

One remarkable surviving example is a monumental Yamantaka Mandala tapestry, now preserved in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Dating to roughly 1330–1332, the massive silk weaving reflects the fusion of Tibetan iconography with refined Yuan craftsmanship.

Governance of Tibet: Administration, Religion, Economy, and Culture

Emperor Wenzong’s Tibet policy rested on four interconnected pillars:

Administrative Oversight

He preserved the Yuan governance structure, ensuring continued central authority while allowing religious leaders significant regional influence.

Religious Patronage

By honoring high lamas and funding monasteries, the court reinforced the priest-patron relationship that underpinned imperial legitimacy.

Economic Support

State resources flowed into temple construction, artistic production, and ceremonial activities—strengthening institutional Buddhism.

Cultural Exchange

The era witnessed deepening interaction between Tibetan and Han societies, accelerating the transmission of ideas, artistic styles, and ritual traditions.

A Lasting Documentary Legacy

One of the emperor’s most significant intellectual projects was sponsoring the compilation of the encyclopedic Jingshi Dadian, which recorded administrative statutes—including those governing Tibet. The work preserved invaluable documentation of Yuan frontier policy and bureaucratic structure.

By systematizing earlier practices, Emperor Wenzong helped maintain political unity between Tibet and the central court while providing institutional models later referenced by subsequent dynasties.

His reign demonstrates how religion, governance, and culture could intertwine to shape imperial strategy—transforming Tibetan Buddhism into both a spiritual force and a framework for statecraft across Eurasia.