Pastoral Life and Animal Husbandry on the Tibetan Plateau

Animal husbandry is deeply rooted in the natural environment of the Qinghai Tibetan Plateau. For thousands of years, pastoral life has shaped the economy, culture, and ecological knowledge of Tibetan communities living between 3,000 and 5,500 meters above sea level.

This high-altitude region is defined by alpine meadows, cold-arid climates, and short grass-growing seasons. These environmental conditions gave rise to a unique transhumance system—seasonal migration between summer and winter pastures—that remains central to pastoral life today.

Tibet is home to the Tibetan people, who call ourselves as Bod-pa. Most Tibetans traditionally live along the middle reaches of the Yarlung Tsangpo River and in the fertile three-river basins of eastern Tibet. For thousands of years, life in Tibet has been closely connected to the land, the grasslands, and livestock. Animal husbandry remains one of the most important economic and cultural foundations of the region.

The Historical Roots of Tibet’s Pastoral Industry

Tibet is major pastoral regions, with a long history of livestock breeding and herding. Archaeological findings suggest that animal husbandry developed from early hunting practices and gradually became an independent and essential livelihood.

Around 4,000 to 5,000 years ago, early Tibetan communities were already raising animals in the southern valleys and eastern river basins. During this period, they also began practicing primitive agriculture. Over time, pastoralism became central to daily survival, trade, and social organization.

Even today, animal husbandry remains a core sector of Tibet’s economy. In many areas, livestock production contributes more to local livelihoods than farming. The region holds one of the largest livestock populations in Asia, reflecting the continued importance of pastoral traditions.

The seasonal grazing system evolved in response to climate and grass cycles:

- Summer pastures: Higher elevations with abundant alpine grass (June–September)

- Winter pastures: Lower valleys with milder conditions

- Spring and autumn transitions: Carefully timed movements based on weather and forage availability

This rotational grazing model helped balance livestock needs with fragile grassland ecosystems.

Vast Grasslands and Natural Resources

The Tibetan Plateau features enormous stretches of natural grasslands, covering approximately 1.24 billion acres. These alpine pastures provide nutrient-rich grasses that support a wide range of livestock.

The landscape directly shapes daily life. In many pastoral areas, herders still live in traditional yak-hair tents. Clothing such as sheepskin robes provides protection against the harsh climate. Diets commonly include beef, mutton, dairy products, and butter tea. Yaks, horses, and mules continue to serve as important modes of transport across high-altitude terrain.

The deep relationship between people, animals, and grasslands defines the rhythm of life across much of rural Tibet.

Main Livestock Varieties in Tibet

Tibet is home to more than 40 varieties of livestock, many of which are specially adapted to high-altitude conditions.

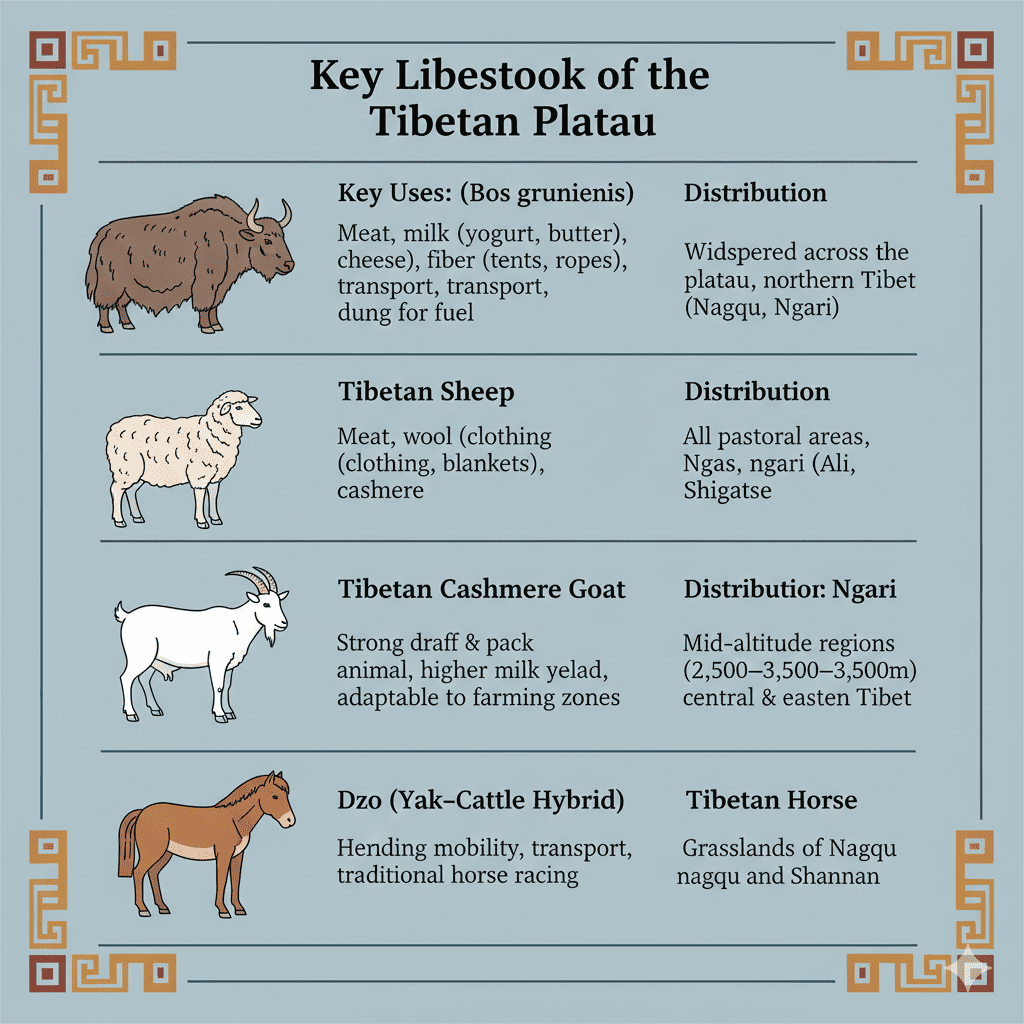

Core Livestock & Their Multi-functional Roles on the Tibetan Plateau

| Livestock | Key Uses | Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Yak (Bos grunniens) | Meat; milk (yogurt, butter, cheese); fiber (yak-hair tents, ropes, robes); transport (“Plateau Boat”); dung for fuel | Widespread across the plateau, especially northern Tibet such as Nagqu and Ngari |

| Tibetan Sheep | Meat; wool (clothing, blankets); cashmere (in some varieties) | All pastoral areas, dominant in Ngari (Ali) and Shigatse |

| Tibetan Cashmere Goat | Premium white cashmere; meat | Primarily raised in the Ngari Plateau; internationally known for fine white cashmere |

| Dzo (Yak–Cattle Hybrid) | Strong draft and pack animal; higher milk yield than yak; adaptable to farming–pastoral zones | Mid-altitude regions (2,500–3,500 meters) across central and eastern Tibet |

| Tibetan Horse | Herding mobility; transport; traditional horse racing festivals | Grasslands of Nagqu and Shannan |

This table highlights how each livestock species plays multiple economic, cultural, and ecological roles within Tibet’s high-altitude pastoral system.

How Altitude Shapes Livestock Distribution

One of the most fascinating aspects of animal husbandry in Tibet is how livestock types vary according to altitude. The extreme environment of the Tibetan Plateau directly determines which animals can thrive.

Above 4,300 Meters

Sheep dominate at the highest elevations. Goats, yaks, and horses are also present, but sheep are the most resilient and common livestock at these altitudes.

Between 4,100 and 4,300 Meters

Yaks become the primary livestock. Sheep, goats, and horses are also raised, creating a mixed pastoral system suited to harsh alpine conditions.

Between 3,000 and 4,100 Meters

This range supports the greatest diversity of livestock. Yaks, sheep, goats, and cattle are widely raised, along with horses, donkeys, mules, and pigs.

Below 3,000 Meters

Cattle are the dominant livestock in lower-altitude valleys. Yaks become less common, while goats, horses, and pigs remain part of local farming systems.

This altitude-based distribution highlights the close connection between ecology, economy, and traditional knowledge in Tibetan pastoral life.

High-Altitude Adaptation: Survival on the Roof of the World

Tibetan livestock are uniquely adapted to the extreme conditions of the Tibetan Plateau. Over generations, natural selection shaped animals capable of surviving in cold temperatures, low oxygen levels, and thin air.

Yaks, for example, have thick fur, large lungs, and strong hearts that allow them to thrive in environments where many other species cannot survive. Tibetan sheep and goats also show strong resistance to cold and limited forage conditions.

These biological adaptations not only sustain local communities but also attract scientific interest. Researchers study Tibetan livestock to better understand high-altitude resilience, climate adaptation, and sustainable pastoral systems.

The Cultural Importance of Animal Husbandry in Tibet

Animal husbandry in Tibet is more than an economic activity—it is a way of life. Seasonal migration patterns, family structures, clothing styles, diet, and transportation systems are all shaped by pastoral traditions.

Livestock provide food, clothing materials, fuel, trade goods, and social identity. Festivals, rituals, and daily routines often revolve around animals and grazing cycles. In many regions, pastoral knowledge is passed down through generations, preserving skills that are deeply rooted in Tibet’s environmental conditions.

The long history of Tibetan pastoralism continues to influence modern Tibet, where traditional herding practices coexist with gradual economic and social change.

Traditional Pastoral Lifestyle on the Tibetan Plateau

Seasonal Rhythms and Shelter

Traditional herders live in black yak-hair tents, designed to resist wind and rain while allowing ventilation. During winter, some families move into stone or earth houses in valley settlements.

Seasonal migration is carefully timed. Herders move to high summer pastures in June or July and return to lower winter areas around October. Decisions are guided by grass growth, snowfall, and long-standing ecological knowledge.

Food and Daily Life

The pastoral diet is centered on dairy products:

- Butter tea

- Yogurt

- Dried cheese

- Tsampa (roasted barley flour mixed with butter or milk)

Meat from yak and sheep supplements the diet, while barley remains the staple grain in farming-pastoral areas.

Community Organization

Pastoral communities often consist of extended families or clan-based groups. Grazing lands and water sources may be shared through rotational agreements. Collective herding strengthens social bonds and spreads labor across households.

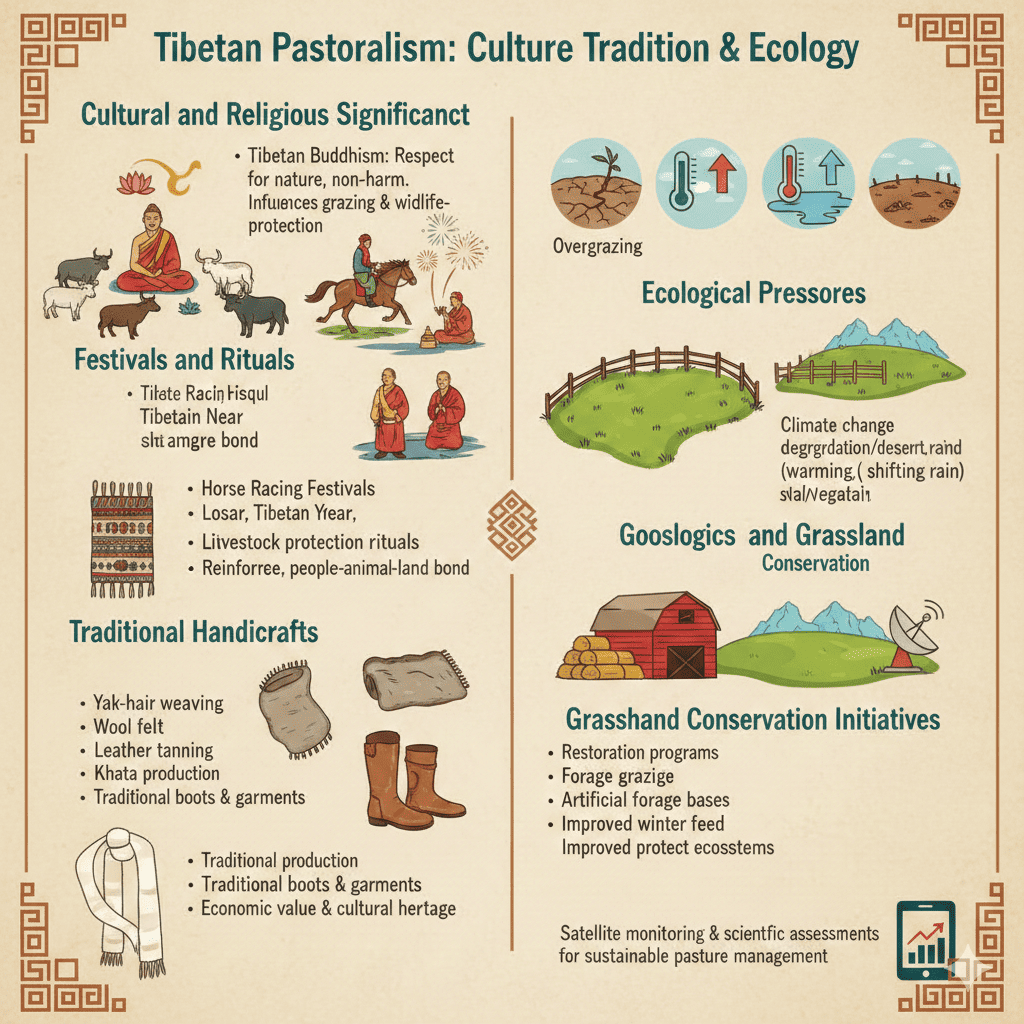

Cultural and Religious Significance

Animal husbandry is deeply connected to Tibetan spiritual traditions. Tibetan Buddhism emphasizes respect for nature and non-harm, influencing attitudes toward grazing practices and wildlife protection.

Festivals and Rituals

- Horse Racing Festivals, such as the Nagqu Horse Racing Festival

- Losar (Tibetan New Year)

- Rituals for livestock protection and grassland blessings led by lamas

These events reinforce community ties and celebrate the bond between people, animals, and land.

Traditional Handicrafts

Pastoral life supports a range of traditional crafts:

- Yak-hair weaving

- Wool felting

- Leather tanning

- Production of khata (ceremonial white scarves)

- Traditional boots and garments

These skills preserve both economic value and cultural heritage.

Ecological Pressures and Grassland Conservation

The Tibetan Plateau is ecologically fragile. In recent decades, several pressures have affected grassland sustainability:

- Overgrazing in certain regions

- Grassland degradation and desertification

- Climate change impacts, including warming temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns

- Permafrost thaw altering water systems and vegetation cycles

Grassland restoration programs, rotational grazing systems, and forage storage initiatives have been introduced to reduce pressure on natural pastures. Artificial forage bases and improved winter feed storage aim to stabilize livestock production while protecting ecosystems.

Satellite monitoring and scientific grassland assessments are increasingly used to support sustainable pasture management.

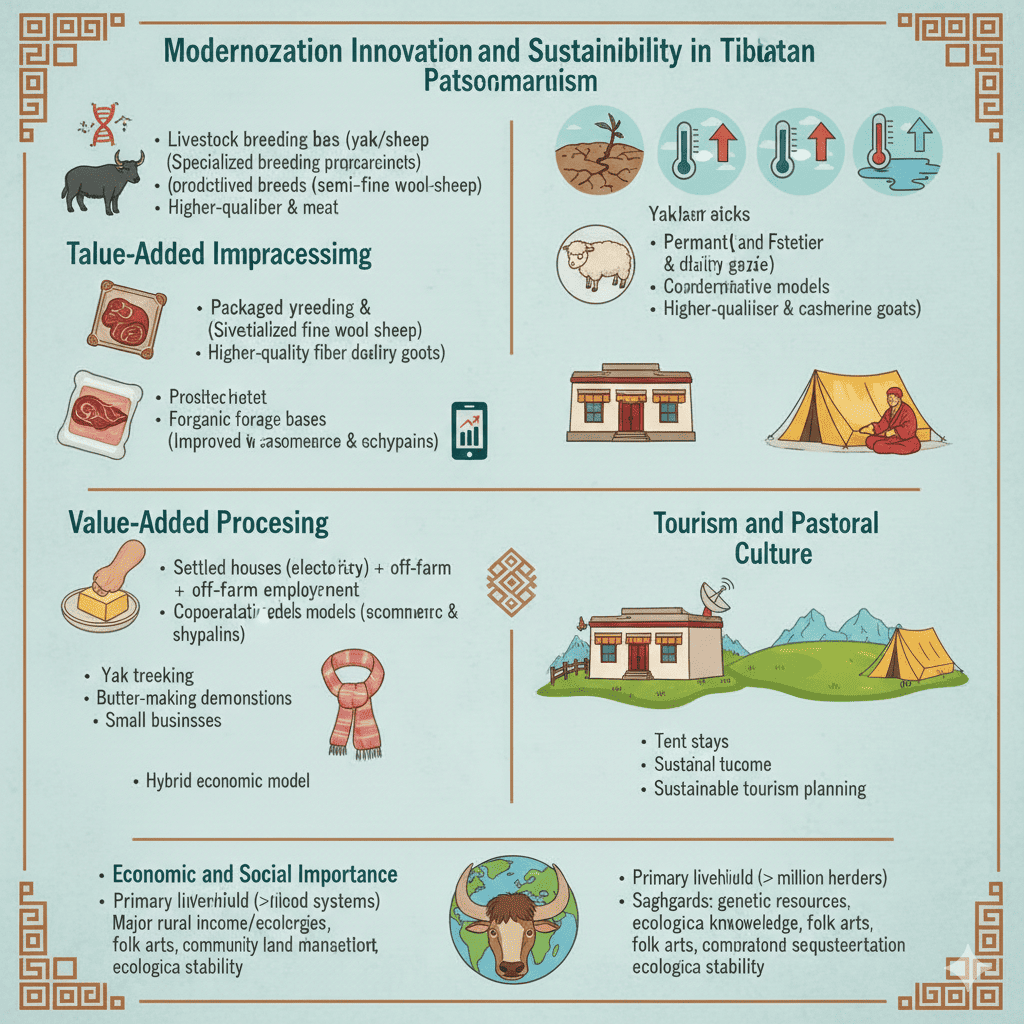

Technological Innovation and Economic Transition

Livestock Breeding and Genetic Improvement

Modern breeding programs have expanded improved yak and sheep varieties. Specialized breeding bases support productivity gains and disease resistance.

New or improved breeds, including semi-fine wool sheep and plateau cashmere goats, contribute to higher-quality fiber and meat production.

Value-Added Processing

Instead of relying solely on raw livestock sales, many regions now focus on processing:

- Packaged yak meat products

- Organic butter and dairy goods

- Premium cashmere textiles

Cooperative-based production models connect herders with broader markets through e-commerce and supply chains.

Settled Pastoralism and Diversified Income

Many pastoral families now live in permanent houses equipped with electricity, water, and internet access. Some combine seasonal grazing with:

- Off-farm employment

- Small businesses

- Pastoral tourism

This hybrid model reflects ongoing economic diversification across rural Tibet.

Tourism and Pastoral Culture

Pastoral villages increasingly participate in cultural tourism. Experiences such as:

- Yak trekking

- Butter-making demonstrations

- Tent stays on alpine grasslands

provide supplementary income for herders. Sustainable tourism planning aims to balance economic opportunity with ecological protection.

Economic and Social Importance

Animal husbandry remains a primary livelihood for more than one million Tibetan herders. It represents a major share of rural income and supports regional food systems.

Beyond economics, pastoralism safeguards:

- Unique plateau livestock genetic resources

- Traditional ecological knowledge

- Folk arts and craftsmanship

- Community-based land management systems

The grasslands of Tibet also play a broader environmental role. They contribute to water conservation, carbon sequestration, and ecological stability across much of Asia.

Sustainable Pathways for the Future

The future of animal husbandry on the Tibetan Plateau depends on balancing tradition and innovation. Sustainable development increasingly focuses on:

- Grassland restoration and controlled grazing

- Improved breeds and efficient feeding systems

- Digital monitoring of pasture health

- Preservation of traditional pastoral knowledge

Tibet’s pastoral system remains one of the world’s most distinctive high-altitude livestock cultures—shaped by ecology, refined through generations, and continuously adapting to modern realities.