Nestled in the western suburbs of Lhasa, at the crossroads of Norbulingka Road and Nationality Road, stands the Tibet Museum. Inaugurated in 1998, the museum sprawls over an area of approximately 20,000 square meters. Its architecture, a harmonious blend of Tibetan styles, is primarily constructed from granite stone. The museum complex includes 12 exhibition halls, a national village, and a multifunctional hall for academic exchanges and events.

Rich Collections

The Tibet Museum boasts a collection of over 120,000 artifacts spanning more than 10 categories, including pottery, porcelain, woodwork, bronzes, gold and silverware, and coins. Among these treasures are over 2000 rare and unique hand-copied ancient texts, holding immense scholarly value. The ethnographic collection reflects the diverse political, economic, and cultural aspects of minority groups, showcasing items like seals, gold and copper stamps, currency, traditional attire, Buddhist statues, scriptures, Thangkas, ritual objects, and other religious art pieces. These collections stand out for their unique ethnic styles and high aesthetic value.

The Eternal Song of the Snowland: An Exhibition of Tibetan History and Culture

Among the museum’s permanent exhibits, “The Eternal Song of the Snowland” stands out for its comprehensive display spanning thousands of years of Tibetan history. This exhibit actively divides into five distinct sections: the Prehistoric Period, the Medieval Period, and the Modern Period of Tibet. With over 2,000 artifacts on display, it offers a rich tapestry of Tibet’s past, highlighting the depth and diversity of its cultural heritage.

The Karub Site: A Glimpse into the Neolithic Age

Not far from the town of Karuo in Chamdo County, the Karub archaeological site presents an unparalleled glimpse into the Neolithic Age within the Tibet Autonomous Region. Recognized as a key cultural relic protection unit in 1996, this site boasts the most systematic and well-preserved collection of artifacts and remains from this era, making it a crucial point of interest for both scholars and visitors alike.

The Twin-Handled Pottery Jar: A Neolithic Masterpiece

Among the treasures unearthed at the Karub site, the twin-handled pottery jar stands out as a testament to the advanced ceramic skills of Tibet’s ancient inhabitants. This unique piece, resembling two beasts standing face-to-face with ingeniously crafted holes for carrying, is not only a functional item but also a ceremonial vessel, reflecting the sophisticated craftsmanship and artistic sensibility of the Neolithic Tibetans.

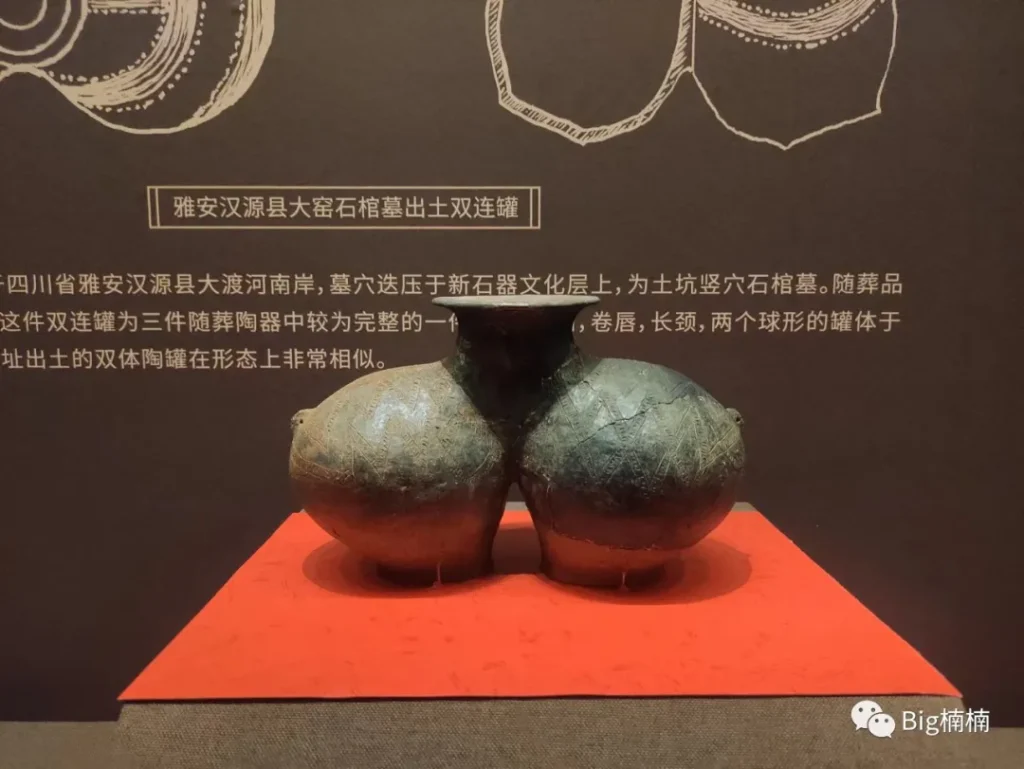

A Comparative Insight: The Double-Handled Pottery

In a fascinating display, the Tibet Museum draws an intriguing comparison between the double-handled pottery jars from the Karub site and similar finds from the Dayao stone coffin tombs in Hanyuan County, Sichuan. This comparison highlights the cultural connections and shared traditions across different regions during the Neolithic period.

The Small-Mouthed, Sand-Contained Yellow Pottery Jar: An Artifact of Daily Life

Another notable find from the Karub site is the small-mouthed, sand-contained yellow pottery jar, characterized by its finely crafted decorative patterns. This jar, with its gently curved shoulder and strategically placed decorative bands, offers a glimpse into the daily life and aesthetic preferences of Neolithic Tibetans, serving as a reminder of the region’s long-standing tradition of pottery making.

The Tibet Museum, through its meticulous curation and preservation of artifacts like these, invites visitors on a journey through time, offering a window into the soul of Tibet. Its exhibitions not only celebrate the artistic achievements and historical significance of the region but also foster a deeper understanding and appreciation for the enduring spirit of Tibetan culture.

Unveiling the Artistry of Ancient Tibet: A Journey Through Time

The Tibet Museum’s collection provides a window into the ancient world of Tibet, showcasing the artistry and craftsmanship of its people through various artifacts and exhibitions. Each piece tells a story, offering insights into the daily lives, beliefs, and cultural exchanges of ancient Tibetans.

The Monkey Face Applique from Karuo Site

One intriguing find at the Karuo site is a pottery decoration featuring a lively monkey face. Designers created this applique to attach to the surface of pottery, vividly capturing the monkey’s features with carefully incised eyes, nostrils, and mouth. The decorators, reflecting the people’s preferences or beliefs, molded it from clay and then affixed it to pottery as a form of embellishment.

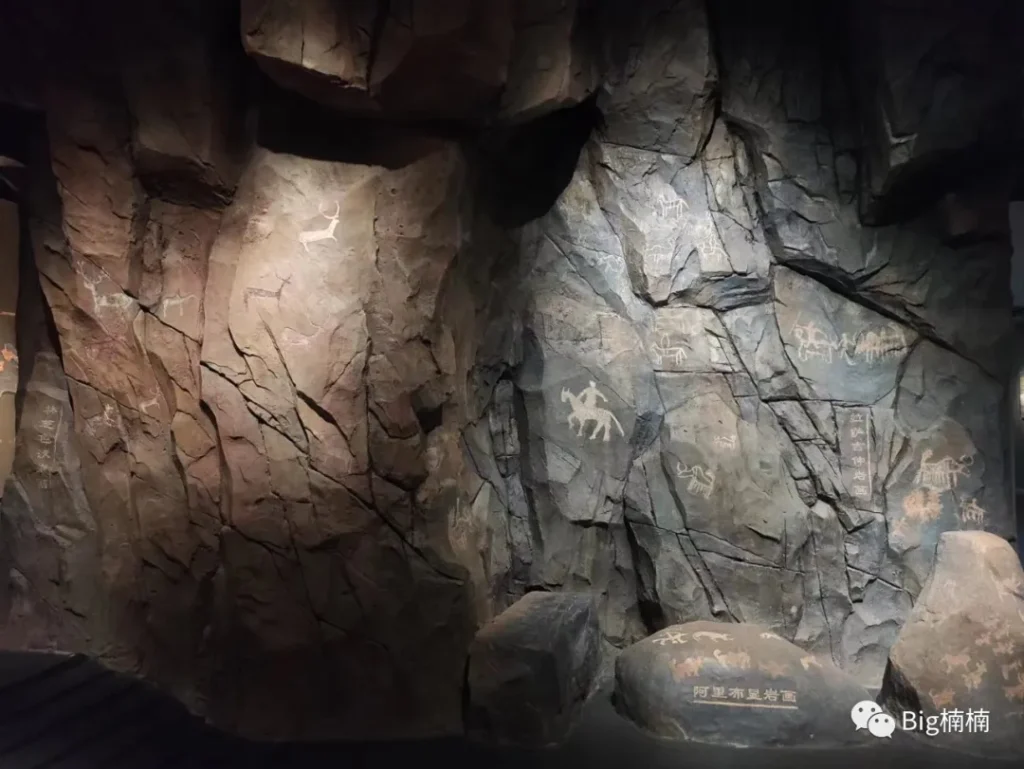

Replicas of Ancient Rock Paintings: A Cultural Tapestry

The museum also presents replicas of significant rock paintings from across Tibet, including the colorful Linzhi Sowo, the intriguing Ali Buxian, and the captivating Lhasa Jizhong rock paintings. These replicas offer a glimpse into the rich tapestry of Tibetan prehistoric art, displaying scenes of life, spiritual beliefs, and the natural world.

The Iron-Handled Bronze Mirror from Qugong Site

A remarkable artifact unearthed at the Qugong site, located in the northern outskirts of Lhasa, is an iron-handled bronze mirror. This site, often hailed as the “Banpo of Lhasa,” stands out for its high altitude, early date, and rich cultural deposits. The mirror, slightly oxidized and decorated with a motif of two birds facing each other, features a thick layer of rust on its iron handle. The presence of a yak pattern on the back of the mirror suggests cultural links between Tibet and the northern grasslands.

Golden Ornaments: Sheep and Horse Figurines from Langkazi Tombs

The Langkazi tombs, a significant archaeological discovery in 2000, yielded a wealth of gold ornaments, including exquisitely crafted sheep and horse-shaped decorations. These pieces, now housed in the Shannan Museum, reflect the high level of artistic achievement and the importance of these animals in ancient Tibetan society.

The “Khawu” Seal: A Testament to the Tibetan Empire

Another fascinating artifact is the “Khawu” seal, discovered in the Nyingchi Nang county Great Tomb and dating back to the Tibetan Empire period. Seals like this were symbols of authority and importance, offering a tangible connection to the administrative and cultural practices of ancient Tibet.

The Bön Religion and Tibetan Medicine Collection

The “Bön Religion Tibetan Medicine Collection,” unearthed from the Gadan Bangchen site, reflects the advanced state of Tibetan medicine during the 8th century. This period saw significant development in medical theory and practice, influenced by exchanges with neighboring regions. The collection includes works by renowned Tibetan physicians like Yutok Yonten Gonpo, marking the establishment of a formal system of Tibetan medicine.

The Coffin Board Paintings from Guolimu, Qinghai

Excavated from Qinghai’s Guolimu, these coffin board paintings vividly depict ancient Tibetan life, including hunting, feasting, trade, and cultural customs. These artworks provide a dynamic insight into the social and economic interactions of ancient Tibet, including the practice of welcoming distinguished guests with a hunt for yak, as recorded in historical texts.

Through these artifacts and exhibitions, the Tibet Museum not only preserves the rich heritage of Tibet but also invites visitors to explore the depth and diversity of its ancient culture. Each piece, whether a simple pottery decoration or a sophisticated gold ornament, serves as a bridge connecting the past to the present, offering a unique perspective on the lives and beliefs of ancient Tibetans.

The Blossoming of Tibetan Civilization Through Cultural Exchange

The marriage of Wencheng and Princesss Bhrikuti to Tibet marked a significant milestone in the history of Tibetan civilization, ushering in a new era of development. This event catalyzed the transfer of various agricultural, construction, and textile production techniques from the Central Plains to Tibet, along with the introduction of new technology into Tibetan culture.

Tubo Sculptures: A Fusion of Art and Devotion

Among the notable contributions from the Tang Dynasty to Tibetan culture are the wooden sculptures of Guanyin and other figures. These artworks embody the deep spiritual connection and artistic exchange between the Tang Dynasty and Tibet, showcasing the rich religious and cultural integration that occurred during this period.

Musical Instruments: A Symphony of Cultural Harmony

The interaction between Tibet and the Central Plains was paralleled by vibrant exchanges with the Western Regions. Instruments like the Rootcha Qin and the Dragon Head Three-String Qin from the Tang Dynasty bear a striking resemblance to the Western Regions’ three-string “Gengqiang Qin,” serving as concrete evidence of the cultural interactions between Tibet and the Western Regions during the Tibetan period.

The Western Regions’ Konghou: A Musical Heritage

The Konghou musical instrument, plays a crucial role in modern folk music, although its contemporary form is a blend of ancient designs with characteristics of the harp and guzheng. The value of this specific Konghou lies in its ability to offer modern audiences a glimpse into the instrument’s historical appearance. It is speculated that this Konghou, along with the below-mentioned Pipa, might have been brought to Tibet by Princess Tritsun.

The Pipa: A Tang Dynasty Legacy

During the Tang Dynasty, the Pipa was played horizontally, a technique now only preserved in the Quanzhou Nanyin musical tradition. This ancient method highlights the evolution of musical practices over time and the enduring legacy of neighbouring countries influences on Tibetan music.

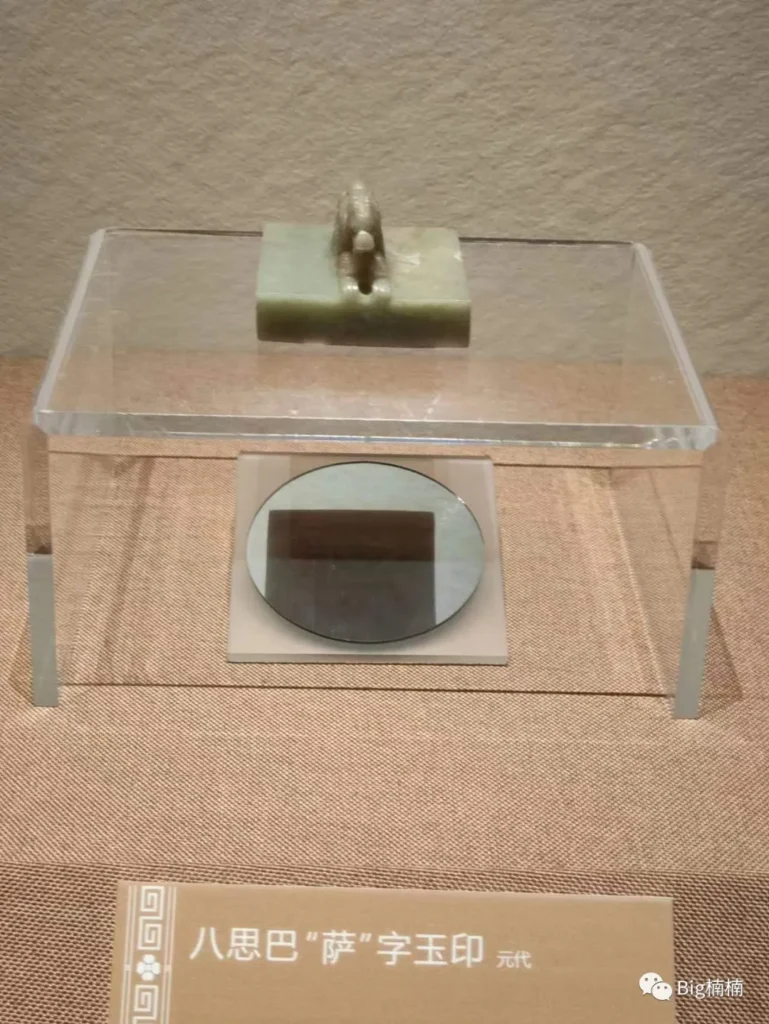

The Sakya Tradition: The “Sa” Jade Seal of Phags-pa

Phags-pa, one of the five founding figures of the Sakya tradition and a nephew of the fourth patriarch, Sakya Pandita, became the leader of the Sakya sect after his uncle’s passing. He was appointed as the Imperial Preceptor by Kublai Khan in 1260. The “Sa” character on the seal likely represents “Sakya,” signifying Phags-pa’s role and the Sakya tradition within Tibetan Buddhism.

Phags-pa’s Portrait Thangka: A Symbol of Religious and Political Influence

After receiving the title of Imperial Preceptor, Phags-pa created the ‘Phags-pa script in 1268 and received the honor of being the first Imperial Preceptor of the Yuan Dynasty in 1270. Later, the Mongol king appointed his brother as the King of Bailan. One brother oversaw religious matters, and the other managed secular affairs, symbolizing the Mongol king’s relationship with the Tibetan lama.

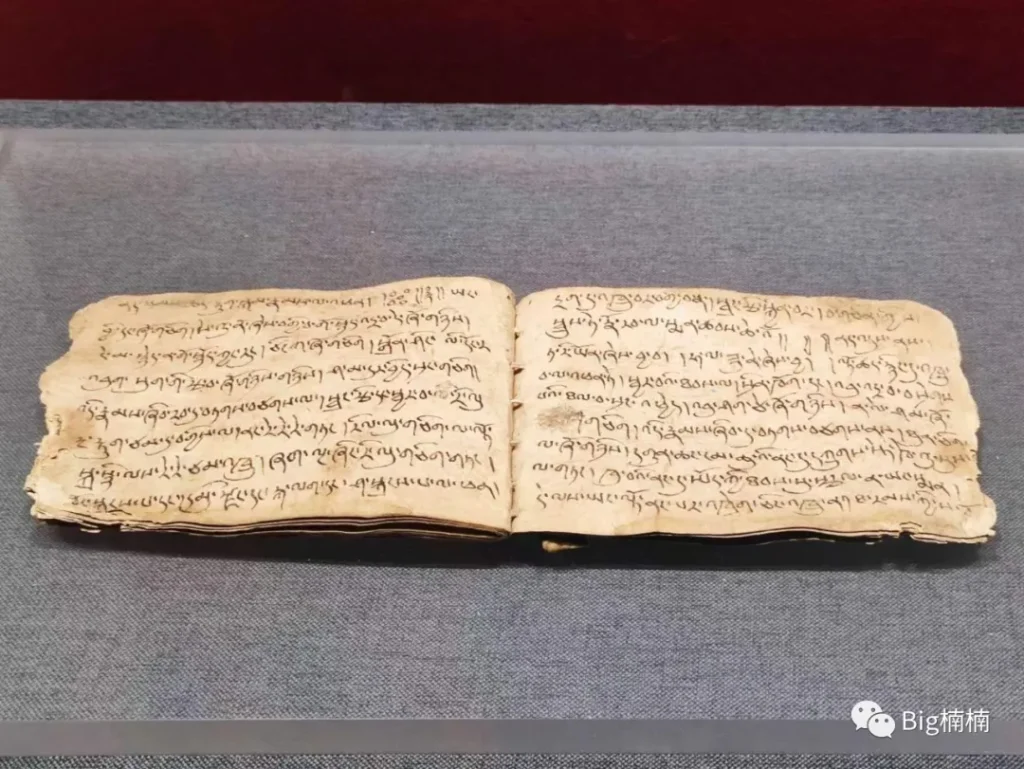

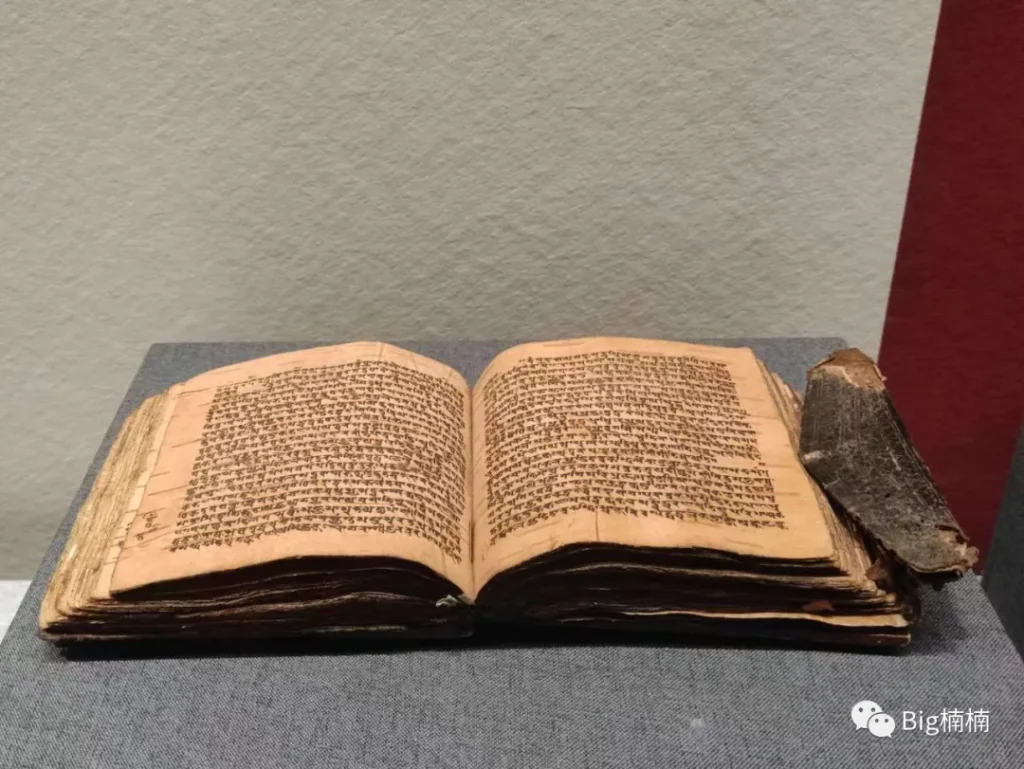

Birch Bark Manuscripts: A Testament to Ancient Literacy

Ancient innovators used birch bark as natural paper, showcasing their ingenuity in writing materials. Birch bark, easily harvested and processed, served as an ideal medium for manuscript production, a tradition that several ancient cultures shared. Writers composed the oldest Buddhist scriptures, including the Gandharan Buddhist texts, on birch bark, underscoring its importance in preserving religious and cultural heritage.

These artifacts and cultural exchanges reveal the rich tapestry of Tibetan civilization, showcasing a history of profound interactions and mutual influences with neighboring cultures. These contributions enriched Tibetan society and laid the foundation for a vibrant cultural legacy that continues to be celebrated and explored today.

The Cultural Legacy of Tibet: Sculptures, Inscriptions, and Thangkas

Tibetan history is rich with stories of cultural exchange, spiritual development, and artistic achievement. Several key artifacts and monuments from different periods illustrate this legacy, showcasing the deep connections between Tibet and its neighboring regions.

Evocative Clay Sculptures from Awang Monastery

In the serene village of Saru within Samada Township, Kangmar County, Shigatse, lies the Awang Monastery, established between the mid-11th and early 12th centuries. The monastery houses a set of clay sculptures in its main hall, depicting Shakyamuni Buddha and his six disciples. These figures, characterized by their elegant and refined appearance, wide sleeves, and flowing robes, are heavily influenced by the artistic styles found in the Yungang and Longmen Grottoes. This fusion reflects the historical intermingling of Buddhist cultures between the Tibet and the Song Dynasty.

The Ren Dharma Cliff Carvings

In Ren Dharma Village, Xiangdui Town, Chamdo, the Ren Dharma cliff carvings stand as a testament to Buddhist artistic achievement. Carved directly into the mountain, these sculptures of Mahavairocana and the eight great Bodhisattvas, accompanied by inscriptions in both Tibetan and Chinese, reveal the collaboration between Tang and Tibetan craftsmen. This site serves as a historical marker of the Buddhist cultural exchange between the two civilizations.

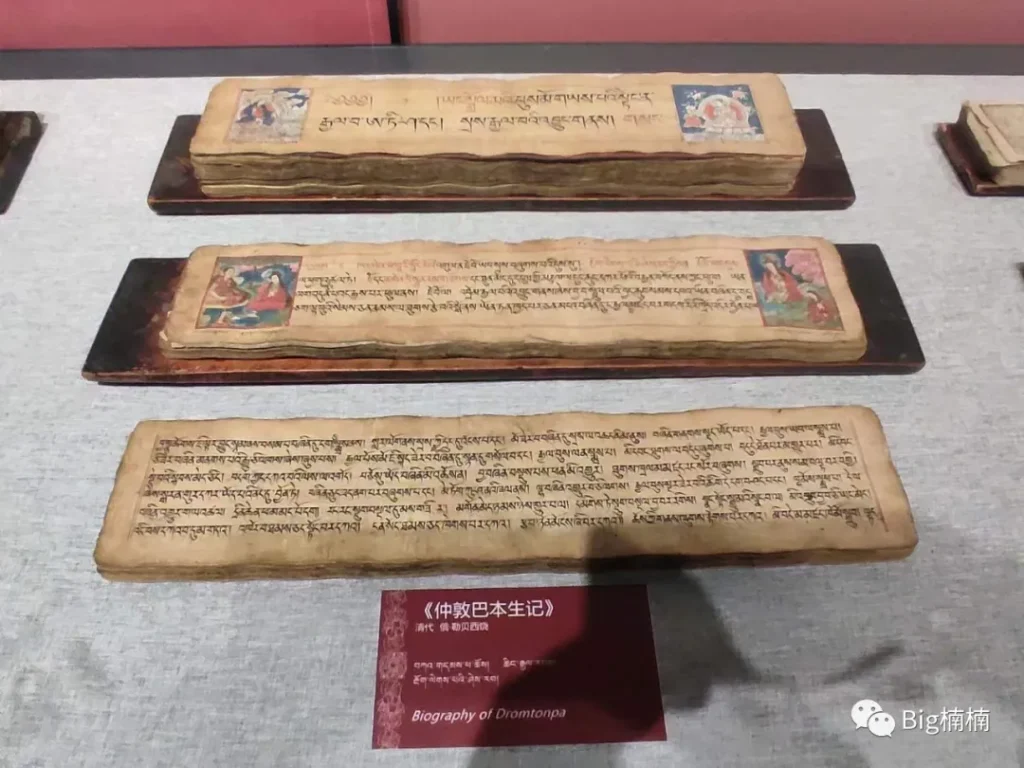

Zhongdunba’s Jataka Tales: A Clear Mirror of Kagyu Tradition

Zhongdunba Jevajong, one of the three main disciples of the master Atisha, founded the Reting Monastery in 1056, marking the establishment of the Kagyu tradition. His younger disciple, O-le-bei-si-rao, continued this legacy by building the Sangphu Neutok Monastery in 1073, which became a foundational center for the study of logic in Tibet.

The Great Compassion Mahayana King’s Seal: A Ming Dynasty Relic

In 1413, the Sakya sect leader Gongga tashi traveled to Nanjing to pay homage to Emperor Yongle of the Ming Dynasty. He was conferred the title of one of the three great Mahayana kings, receiving a decree and a gold seal. The Great Compassion Mahayana King’s seal in collection, made of ink jade, likely represents the seals given by the Ming king to subsequent Mahayana leader.

The Great Compassion Mahayana King’s Embroidered Thangka: A Ming Masterpiece

In the early years of Ming Dynasty, emperor repeatedly invited Tsongkhapa, the founder of the Gelug tradition, to Beijing. Due to his politic apathy stand, Tsongkhapa sent his less known disciple Shakya Yeshe just for courtesy in 1414. Shakya Yeshe was bestowed the title “Great National Teacher of the Western Heaven” upon his visit, and during his subsequent visits in 1429 and 1434, he was honored by Emperor Xuande as one of the three great Mahayana kings, the “Great Compassion Mahayana King.” The embroidered thangka displayed in collection was commissioned by Emperor Xuande and presented to him, showcasing the intricate and exquisite craftsmanship of the Ming court.

The Karmapa’s Scroll of Auspiciousness

One of the museum’s prized possessions is the “Karmapa’s Scroll of Auspiciousness,” a long scroll measuring 4968 centimeters in length and 66 centimeters in width. It depicts various auspicious clouds and scenes witnessed during the process of blessing rituals conducted by the Karmapa, Deshin Shekpa (1384—1415), in the early part of 1407. Invited to Nanjing and Mount Wutai in Shanxi, the Karmapa held grand rites to bless the late Ming Dynasty founder, Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang (reigned 1368—1398), and his queen.

The manifestation of auspicious signs during these rituals greatly pleased the emperor, who then bestowed upon the Karmapa the honorary title “Tathagata of Ten Directions, the Most Victorious Circular Wisdom.” He also gave the Karmapa a black ceremonial hat edged with gold thread as an heirloom.

The scroll is a detailed daily record of events from February 5 to 18 and March 3 to 18, 1407, totaling 49 segments. Each segment meticulously illustrates the treasure tower where the Karmapa resided and the altars of blessing, complete with inscriptions in Chinese, Tibetan, and Mongolian. The artwork stands out for its strict composition, delicate brushwork, and vibrant colors, making it a true masterpiece and a testament to the rich cultural and religious heritage of Tibet.

Treasures of Tibet: From Sacred Seals to Exquisite Ivory

The Golden Seal of the Seventh Dalai Lama

In the heart of Tibet’s rich history lies the esteemed Golden Seal bestowed upon the Seventh Dalai Lama, Gelsang Gyatso (1708—1757), by the Qing Dynasty government in 1724. Crafted from 230 taels of gold, weighing 8257 grams, this seal stands as a symbol of authority and sanctity. Its square shape, measuring 11.5 cm on each side and standing 10.1 cm tall, is adorned with a traditional Ruyi knot. Engraved in Han, Mongolian, Manchu, and Tibetan scripts, this seal encapsulates the reverence and prestige of the Dalai Lama, making it an invaluable artifact of Tibetan culture.

The Ivory Carving Masterpiece

The art of ivory carving in Tibet reaches its zenith with a stunning piece measuring 1.745 meters in length. This intricate work features 25 Buddhist niches and 88 figures, surrounded by detailed depictions of palaces, temples, landscapes, and flora, all spiraling along the natural tapering form of the ivory. A bead-and-ribbon motif segments the entire piece into nine distinct levels, with twin dragons dividing each level and showcasing vibrant scenes from the life of Siddhartha Gautama (Buddha). From his birth to enlightenment and eventual nirvana, this piece vividly narrates the Buddha’s journey, displaying the carver’s exceptional skill and creativity.

The Imperial Seal and Tibetan Buddhism’s Influence in the Yuan and Ming Dynasties

The relationship between the Yuan Dynasty and Tibetan Buddhism is exemplified by the title of “Imperial Preceptor” (Dishi), first awarded to Phags-pa Lama after his initial appointment as the State Preceptor by Kublai Khan in 1270. This title marked the official representative of the Yuan Dynasty in Tibet, and the seal used during this period featured the ‘Phags-pa script. Throughout the Yuan Dynasty, there were fourteen Imperial Preceptors, most of whom were related to Phags-pa, signifying the Sakya sect’s prominence and its development during the Yuan Dynasty.

The Artistry of the Tibet in medieval period: Cloisonné and Buddhist Ritual Objects

In Medieval period saw the creation of unique cultural artifacts, including the cloisonné lotus pattern monk’s cap pot and its cover, a design originating in the Sakya Dynasty with strong ethnic minority influences. Additionally, from the same period are silver-inlaid conch shells and alloy copper Vajra (diamond) bells and scepters. These items not only reflect the aesthetic preferences of the time but also the continuing integration of Buddhist practices and symbols into Tibetan rich art and culture.

Ganden Phodrang Dynasty Edicts to the Jetsun Dampa Khutuktus

The Ganden Phodrang Dynasty’s Power with Tibetan Buddhism and Politics is illustrated through edicts awarded to the 8th and 9th Jetsun Dampa Khutuktus in 1806 and 1818, respectively. The Jetsun Dampa Khutuktus, and Changkya Rinpoche , are among the highest-ranking lamas in the Gelug tradition of Mongolian Buddhism, with their ancestral monastery located in the Ganden Monastery in Lhasa. The title of head lama are an honorific given by the Ganden phodrang Dynasty to high-ranking lamas in Mongolian regions, symbolizing the impact and concern for these spiritual leaders.

A Rich Tapestry of Historical Edicts

The wealth of edicts, imperial decrees, and sacred directives within the exhibit speaks volumes about the intricate relationship between the Qing and Tibetan Leader. Exploring this collection offers a deep dive into the historical dynamics of religious and political interplay, necessitating over two hours for a thorough examination. This exploration is highly recommended for anyone interested in understanding the complex history of Tibet and its interactions with kings in China.

The Golden Urn: A Symbol of Divine Selection

The Golden Urn, a significant ceremonial object from the Qing Dynasty era, was introduced by Emperor Qianlong in 1792 as a means to ensure a fair selection process for the reincarnations of important Mongolian and Tibetan lama. This urn, made entirely of gold and standing 34 cm tall, features a slender neck, a round body, and is embellished with lotus petals, intertwined lotus patterns, and various precious stones. Inside, a cylinder holds five ivory lots, each inscribed with names in Manchu, Han, and Tibetan scripts, to be drawn in the search for the reincarnated souls, marking a blend of spiritual belief and imperial oversight.

Discovering Tibet’s Homestay Culture: “Closest to the Sun”

Experience the unique and vibrant culture of Tibetan homestays in the exhibition “Closest to the Sun.” This immersive showcase reconstructs scenes such as weddings and New Year celebrations, offering a glimpse into the customs and lifestyles of the Tibetan people.

The Essence of Tibetan Weddings

Tibetan weddings, rich in tradition and rituals, unfold in a series of stages: proposal, engagement, bride fetching, and the wedding ceremony itself. Despite regional variations across the three major Tibetan areas—Ü-Tsang, Kham, and Amdo—the core processes remain consistent.

Proposal: A pivotal stage in Tibetan marriage customs. Traditionally, once a suitable match is found, the proposing party, regardless of the distance, must present a white scarf (khata) and barley wine to the prospective bride’s parents as a gesture of proposal.

Engagement: Following the acceptance of the proposal, families of both the bride and groom meet to discuss and finalize the wedding details, such as the date and scale of the celebration.

Bride Fetching: The arrival of the groom’s procession is met with joyous bell sounds and the neighing of horses, welcoming the couple with blessings. The bride and groom, marked with colorful arrows and accompanied by a majestic cavalcade, become the center of attention, stepping down from a mat adorned with representations of Yongzhong to cross the threshold into marital life.

Wedding Ceremony: The celebration is marked by auspicious patterns drawn with white lime in front of the house and in the courtyard, and the burning of juniper incense to invoke divine blessings. Amidst this joyous and harmonious atmosphere, neighbors and friends come bearing gifts and white scarves to offer their best wishes.

Celebrating the Tibetan New Year

The Tibetan New Year, or Losar, is the most significant festival for Tibetans, filled with unique activities. One such tradition is “Guthuk” on the 29th day of the 12th month, where families gather to eat a special noodle soup containing dumplings with different fillings symbolizing various omens—chili for talkative, wool for kind-heartedness, and salt for laziness. This meal serves not only as a family gathering but also as an educational moment, integrating cultural beliefs and family values.

Through these vibrant customs and festivals, the exhibition “Closest to the Sun” invites visitors to explore the depth of Tibetan homestay culture, offering insights into a community that lives in harmony with nature and tradition, enriching and preserving its cultural legacy for generations to come.

The Tibetan New Year, known as Losar, is rich with traditions and customs that reflect the vibrant culture of Tibet. Among these traditions, the eve of the New Year, called “Nagga” in Tibetan, is a day filled with final preparations and anticipation for the year to come.

The Eve of New Year: A Day of Preparation

On Nagga, families are busy cleaning their homes and ensuring personal hygiene. It’s a day for making final preparations for the New Year, which includes arranging offerings like grain containers (chemar), fried pastries (kapse), barley wine, sheep’s head, fruits, tea, butter, and salt atop the main hall’s cabinet. Auspicious symbols, the Eight Auspicious Symbols, are drawn with tsampa or white flour at the front door, wishing for a prosperous year for crops and livestock.

The First Day of Losar: Rituals and Taboos

The first day of Losar is the most significant and filled with various taboos and rituals. Before dawn, families rush to nearby wells or rivers to fetch the first water of the year, believed to bring fortune. Neighbors exchange chemar to wish each other well. Dressed in their finest, families gather to enjoy festive meals, adhering to taboos like not sweeping, arguing, or speaking loudly.

Respecting Natural Laws and Special Customs

In Tibet, people traditionally follow natural laws and often arrange daily activities based on astrological calculations. However, the third day of Losar is an exception, embraced by the saying, “Do not inquire about astrological calculations on the third.” Traditionally, this day is ideal for communal activities like changing prayer flags on rooftops, hanging prayer flags on mountains, and horse racing.

Tibetan Opera: A Cultural Heritage

Tibetan opera, known as “Ache Lhamo” in the Tibet Autonomous Region and “Namu” in Qinghai Province, is a national intangible cultural heritage recognized by UNESCO on September 30, 2009. It’s a performance art that has its roots in folk songs and dances, storytelling, and religious ceremonies and arts.

This rich tapestry of customs and traditions surrounding the Tibetan New Year not only showcases the unique cultural heritage of Tibet but also offers a glimpse into the daily lives and spiritual practices of the Tibetan people. Through these age-old customs, the spirit of Tibet continues to thrive, preserving a legacy that is celebrated and explored by people around the world.

The Art of Tibetan Textiles: A Tradition of Beauty and Craftsmanship

The Tibetan textile craft system, primarily utilizing sheep and yak wool, is a vibrant expression of local characteristics and ethnic identity. This craft encompasses a meticulous approach to pattern design, color coordination, textile processes, and dye preparation. Across both agricultural and pastoral regions, it’s common to spot people spinning yarn with spindles and using ancient-looking looms. The Tibetan people’s appreciation for beauty shines through in the colorful pulu (woolen fabric) and kaden (rugs), among other textiles.

Pulu is categorized into four types based on the material used, with kema being the highest quality. Kema is woven from the wool underneath a sheep’s neck, using wool for both warp and weft, and is used to make high-quality garments such as robes and bandanas. Bhudzhi, made from the wool on a sheep’s shoulders and back, is used for robes and trousers. Trima, a medium-quality pulu, is made from any wool, typically in brown or black, and used for robes and monastic garments. Lastly, chingzi is considered the lowest quality pulu and is used for winter clothing.

Thangka Painting: A Unique Artistic Expression within Tibetan Culture

Thangka painting stands as a distinctive form of art within Tibetan culture, characterized by its ethnic features, rich religious themes, and unique style. It has been recognized as a national intangible cultural heritage. A notable piece within this exhibition is a thangka depicting the story of “Gesar Winning the Horse Race,” based on the epic tale of Gesar overcoming numerous challenges to emerge victorious and become the king of Ling.

The exhibition also showcases various utensils common in Tibetan daily life, offering insights into the similarities and differences between Tibetan customs and those of the Central Plains.

Daily Life and Religious Influence in Tibetan Artifacts

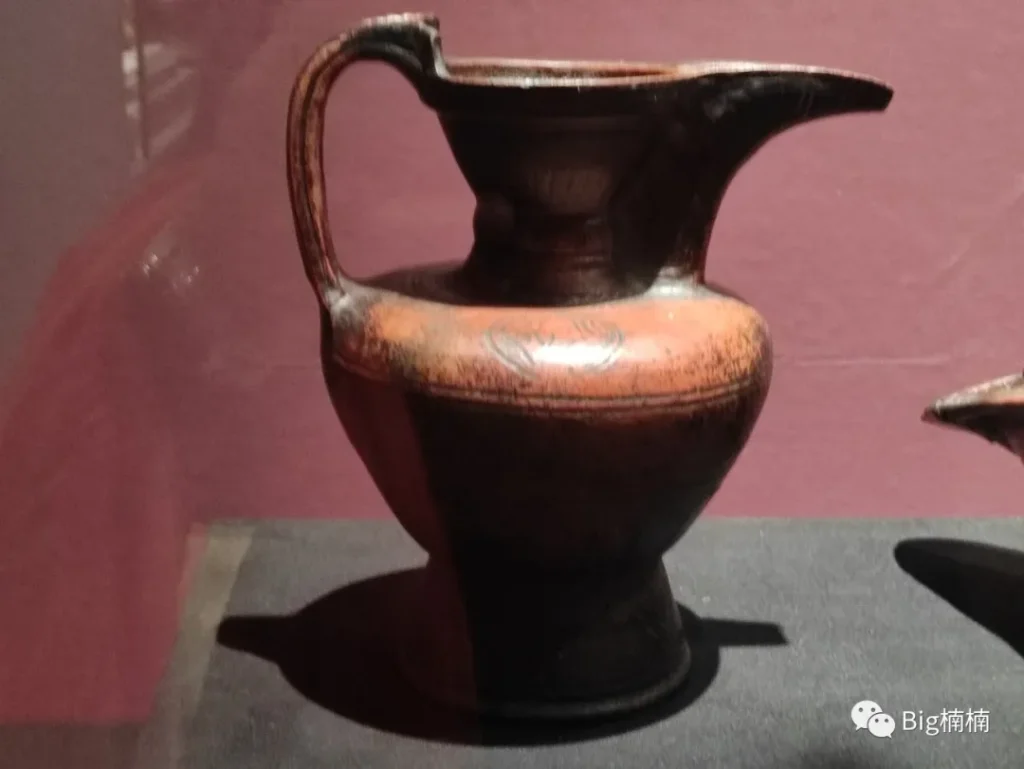

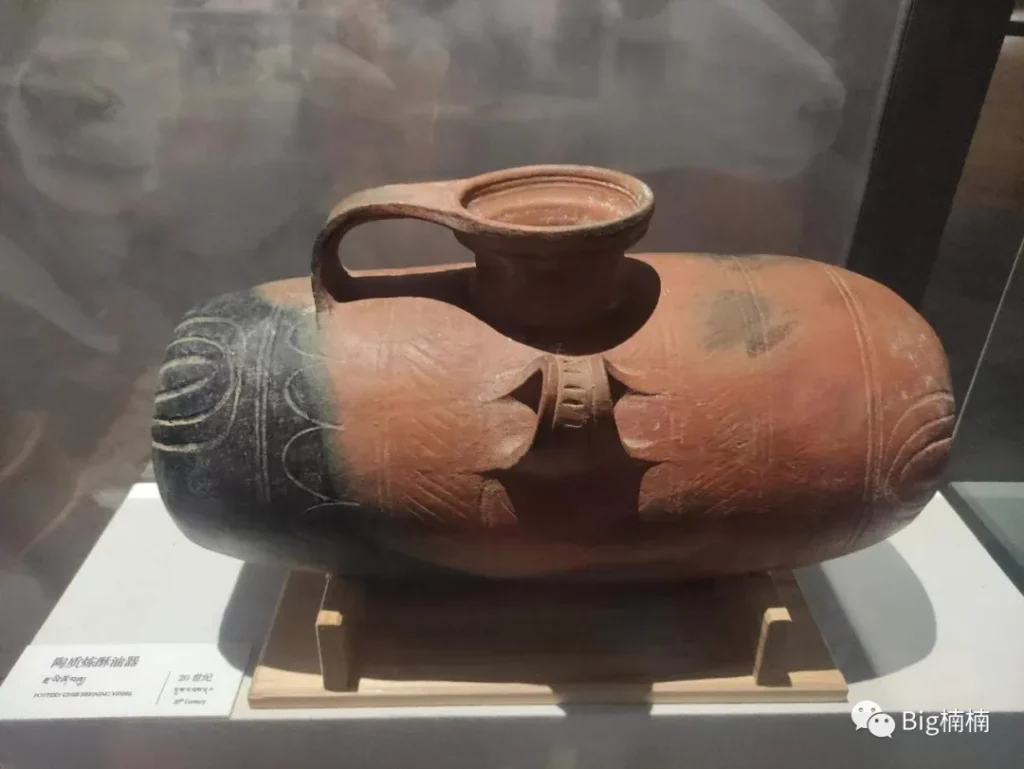

The artifacts on display include terracotta connected lamps and conch shells from the 20th and 21st centuries, copper bells from the late 19th to 20th centuries, a terracotta snow chicken wine pot, and a single-handled pot from the 20th century. Additionally, there are a silver-gilt Eight Auspicious Symbols teapot, a silver-gilt dragon pattern plate from the late 19th to 20th centuries, and an iron sword with inlaid jewels from the 18th to 19th centuries, alongside a terracotta butter churn from the 20th century.

Tibetan Culture: A Living Tradition Passed Down Through Song

Tibetan history is predominantly documented by monks, blending religious and secular content. Due to sectarian reasons, these writings may not fully capture the objective essence, especially in descriptions of productive activities. However, Tibetans have transformed their experiential wisdom into songs passed down through generations, becoming a living aspect of Tibetan culture.

This exhibition, though small in size, is rich in content and offers an engaging look into the fascinating aspects of Tibetan life and culture, providing a thoughtful transition from the somber realities of serfdom to the vibrant expressions of traditional craftsmanship and artistry.

Tour Visit Tips:

- Ticket Purchase: Ensure to buy a ticket before visiting.

- Visiting Hours: The site is open for visitors from 9:30 AM to 6:00 PM.

- Transportation: Getting there is easy, whether you prefer to drive yourself, take a taxi or a bus. Biking or walking are also viable options for a more leisurely approach.