Discovering Early Tibetan Banknotes: A Historical Perspective

Exploring the origins of Tibetan currency unveils a fascinating journey through time, beginning in the 8th century when King Songtsen Gampo unified the plateau, establishing the Tibetan Empire. This era witnessed the emergence of the Tufan dynasty and the formation of feudal estates, fostering significant developments in commercial trade. Despite the region’s unique geographical challenges, the demand for currency soared, paving the way for the introduction of paper money.

Historical records suggest the presence of a currency known as “Sangtram” during the Tibetan Empire, believed to be the translation of the Chinese term for “copper coins.” This indicates the early use of paper currency as a medium of exchange in commercial transactions. Additionally, accounts from the Dunhuang Manuscripts mention the collection of gold taxes by Tibetans in 708 AD, further illustrating the region’s flourishing economy during this period.

Turbulent Times and Monetary Fragmentation

By the mid-9th century, the collapse of the Tibetan Empire plunged the region into a period of fragmentation and turmoil, significantly impacting its monetary economy. Various factions vied for power, leading to the issuance of separate currencies and causing monetary chaos that hindered the development of commercial trade.

Resurgence and Yuan Dynasty Influence

It wasn’t until the 13th century that Tibet began to regain unity, ushering in a gradual restoration of its monetary economy. During the Yuan Dynasty, Tibetan territories fell under imperial rule, prompting the issuance of paper currency by the Yuan government to strengthen control. Known as “Zangchao,” these banknotes played a pivotal role in stabilizing Tibet’s currency market and revitalizing commercial trade, fostering closer economic ties with the central plains.

While the issuance of Zangchao brought stability, it also posed challenges. The region’s rugged terrain made transportation and preservation of paper currency difficult, limiting its circulation. Additionally, Tibet’s relatively underdeveloped economy resulted in a scarcity of Zangchao, further constraining its use.

Transition and Fragmentation

By the 14th century, Tibet entered a new era of fragmentation, marked by the issuance of diverse currencies by competing powers, disrupting economic activities once again. It wasn’t until the 17th century that Tibet gradually restored unity, accompanied by a resurgence in its monetary economy. However, detailed records of this period’s currency remain scarce due to Tibet’s unique historical context and geographical constraints.

Early Tibetan banknotes trace their roots to the era of King Songtsen Gampo, marking the beginnings of a burgeoning monetary economy that played a crucial role in commercial trade. Yet, due to Tibet’s distinctive historical backdrop and geographical challenges, specific details about these early banknotes remain elusive.

Modern Tibetan Banknotes

The term “Tibetan currency” encompasses both coins and paper money circulated by the former Tibetan administration mint. Among these currencies, five variations of paper money, adorned with single and multiple colors, were printed in 1913 and remained in use until 1959.

Gold-Backed Banknotes

Tibetan banknotes were backed by a gold reserve system, ensuring their stability and value. In 1912, a local bank was established in Tibet, initiating the production of wooden engraving moulds and hand-printed monochrome banknotes of various denominations the following year. These banknotes were crafted from paper sourced from Nyingchi City, made from flowering wolf poison grass, renowned for its durability and resistance to pests.

Flowering wolf poison grass

Counterfeit Detection and Authentication

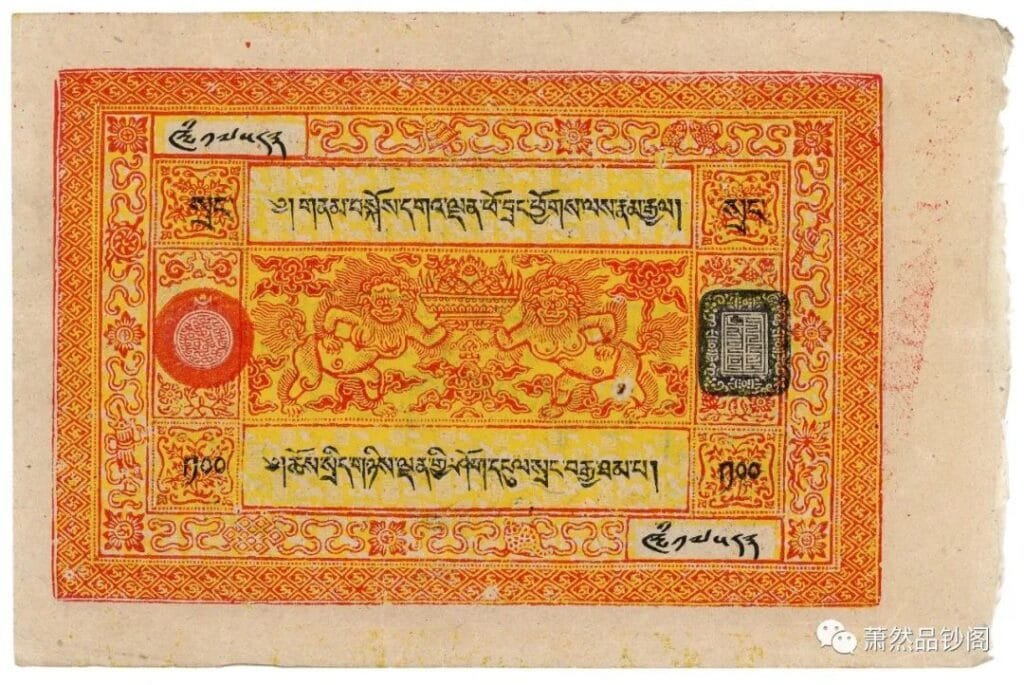

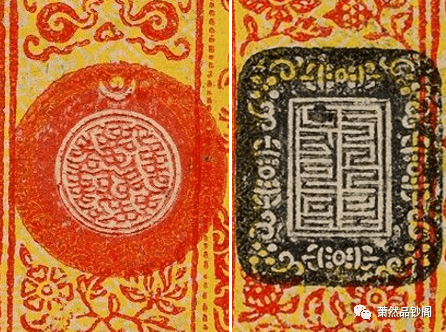

To combat counterfeit currency, the organization “Aiba Yundan” was established, employing methods such as manually inscribing the banknote number by Gongcheng Banjue and affixing a rectangular coinage black emblem on the banknote’s front. This meticulous process continued until 1959, ensuring the authenticity of Tibetan banknotes.

Regent Dazza, acting for the Revital regime

Endorsement by Regent Dazza

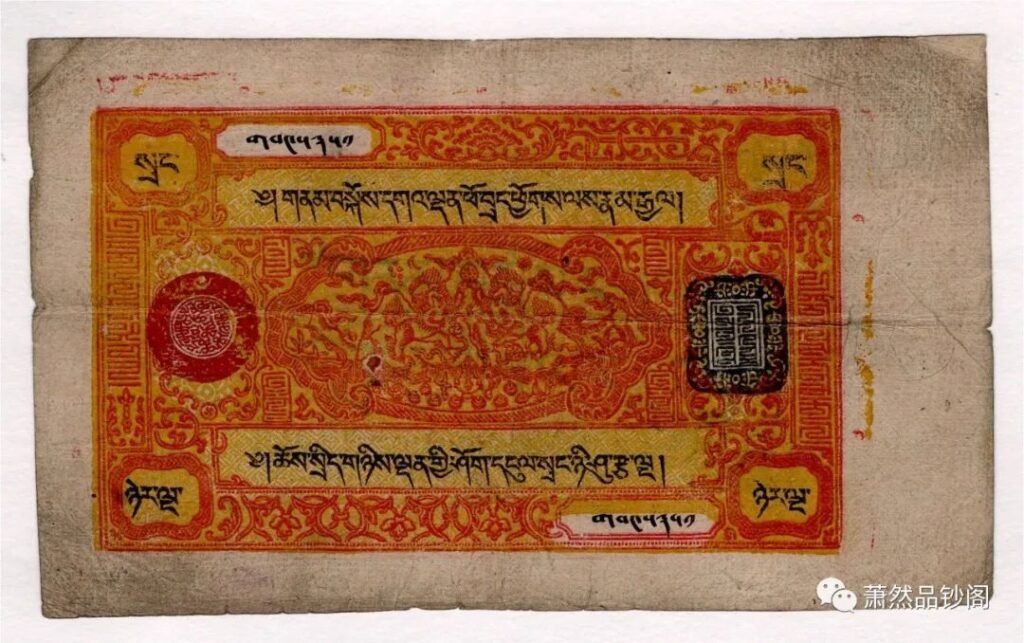

Under the guidance of Regent Dazza, representing the Reting administration, Tibetan silver notes were produced in various denominations. In 1941, 5 taels of Tibetan silver and 10 taels of colored bills were minted, followed by 25 taels of Tibetan silver in 1949. These denominations played a crucial role in Tibet’s economic transactions during this period.

5 taels of Tibetan silver

10 taels of silver notes

25 taels of silver

Exquisite Design and Craftsmanship

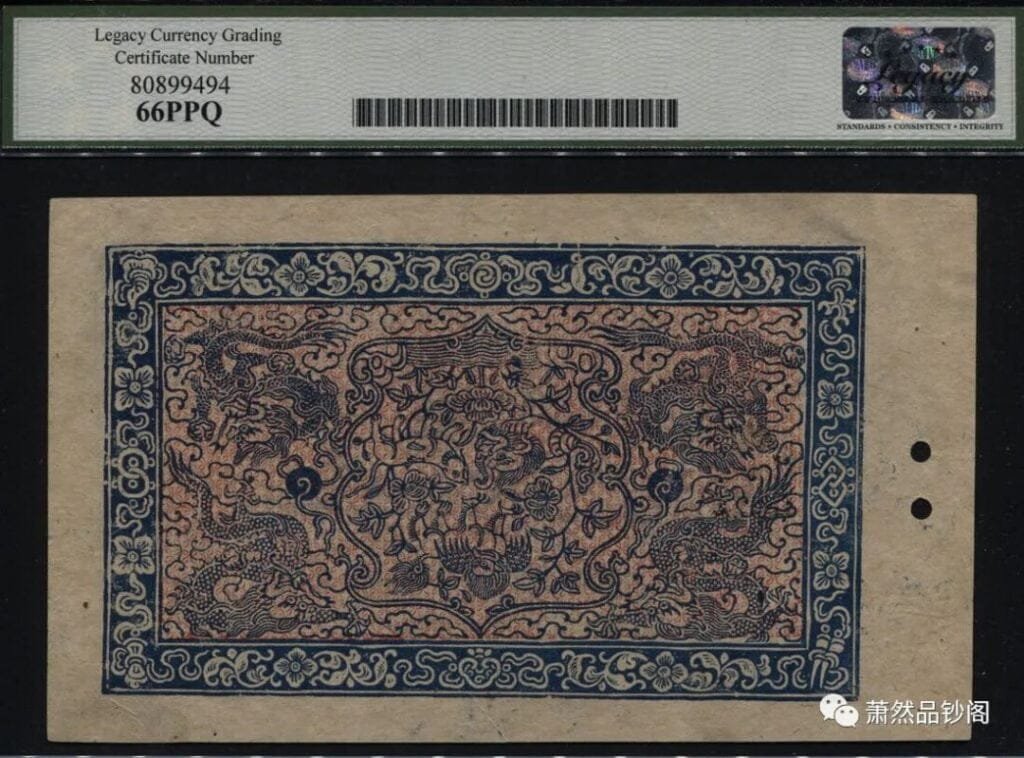

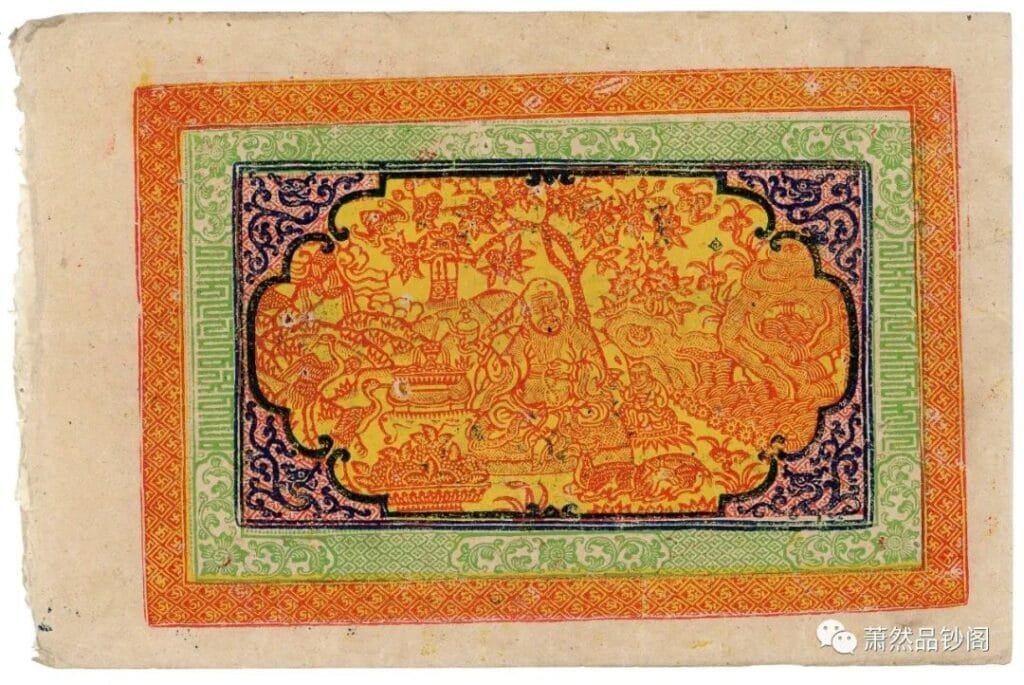

In 1945, the production of 100 silver banknotes required approximately 204 kilograms of gold to procure the necessary raw materials. Measuring 214×138 mm, the 100-denomination banknote, also known as the “Tibetan Silver Banknote,” surpassed the dimensions of the current 100-yuan red banknote of the RMB. Renowned for its intricate color overprinting design, it stands as one of the most exquisite among the nearly 10 circulating banknotes issued by the former Tibetan local government, boasting the highest face value and the longest period of issuance.

100 taels of Tibetan silver

The Evolution of Tibetan Silver Notes

In 1937, with the approval of Tibet’s regent Reting, a groundbreaking method was employed to produce a series of one hundred Tibetan silver note sets using an iron-shaped etching plate. These notes, bearing the red seal of the Dalai Lama on the fifty-Trangka denomination, marked a significant milestone in Tibet’s monetary history. Additionally, the rectangular seal of the Drachi Mint continued to be utilized, ensuring authenticity and continuity in currency production.

Following the liberation of Tibet in 1959, the Tibet Autonomous Region’s Preparatory Committee, with approval from the central government, issued a statement on August 10th regarding the acceptance of Tibetan currency. According to this statement, “Tibetan silver 100 two-colour notes can be exchanged for 2 yuan,” signifying a transitional period in Tibet’s currency exchange policies.

Intricate Design and Symbolism

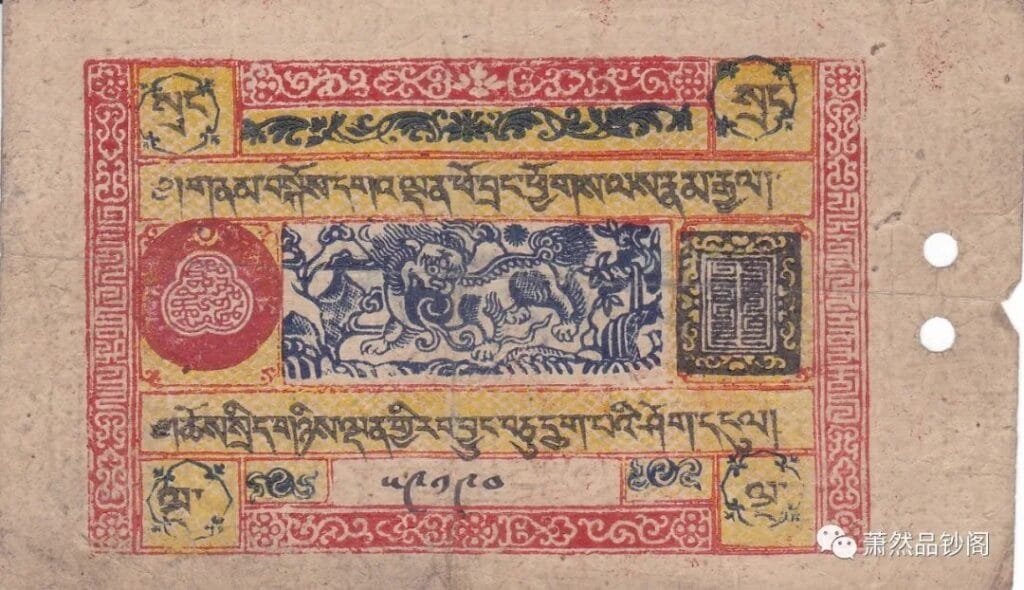

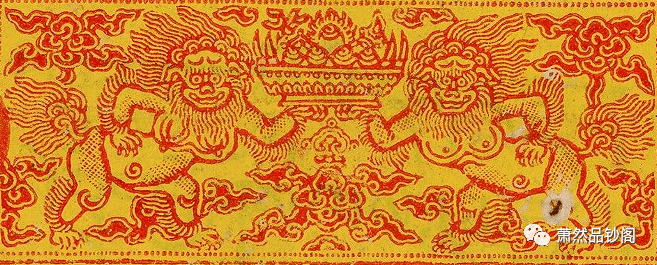

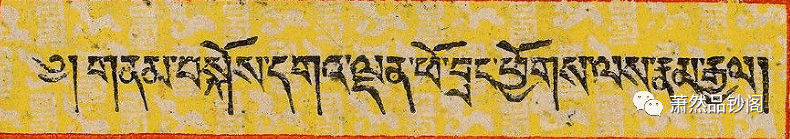

The 100 pairs of Tibetan silver notes feature a horizontal design on the front, measuring approximately 96.6 mm in length and 37.5 mm in width. At the center of the design lies a red map against a yellow background, flanked by two lion-faced creatures known as the “five-faced king,” holding a treasure basin amidst auspicious clouds. The notes boast three layers of paperback borders, adorned with Tibetan text and intricate designs, symbolizing the invincibility of the Ganden Phodrang government and the unity of politics and religion.

The local government of Tibet is invincible.

The unity of politics and religion is one hundred taels of Tibetan silver.

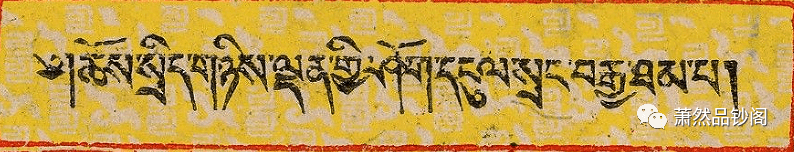

Within the rectangular frame having four corners, a Tibetan numeral in black is placed on top of a red floral and grass design against a yellow backdrop. The Tibetan numeral “two” is inscribed in the upper left and right corners, while the lower left and right corners feature a Tibetan lowercase currency symbol with a value of “100”.

The flowers and clouds are imprinted on both the left and right edges of the inner border, with the left featuring the Dalai Lama seal in a circular shape and coloured red, while the right showcases the Phagpa letter seal in a rectangular form and coloured black.

The centre panel is uniformly adorned with eight propitious images set against a white backdrop embellished with red designs, with two on either side. The uppermost panel showcases the Victory Bell and Pisces, while the bottom panel exhibits the auspicious knot and the conch.

Victory Bell and Pisces

Auspicious knot and snail

On the left are the warping wheel and the umbrella, and on the right are the vase and the lotus flower.

The upper box’s left side and the lower box’s right side have concealed handwritten banknote numbers. The red diamond grid pattern adorns the outer frame on a yellow background, and the diamond grid also features Tibetan letters and ten thousand-character ornaments.

Symbolic Imagery and Artistry

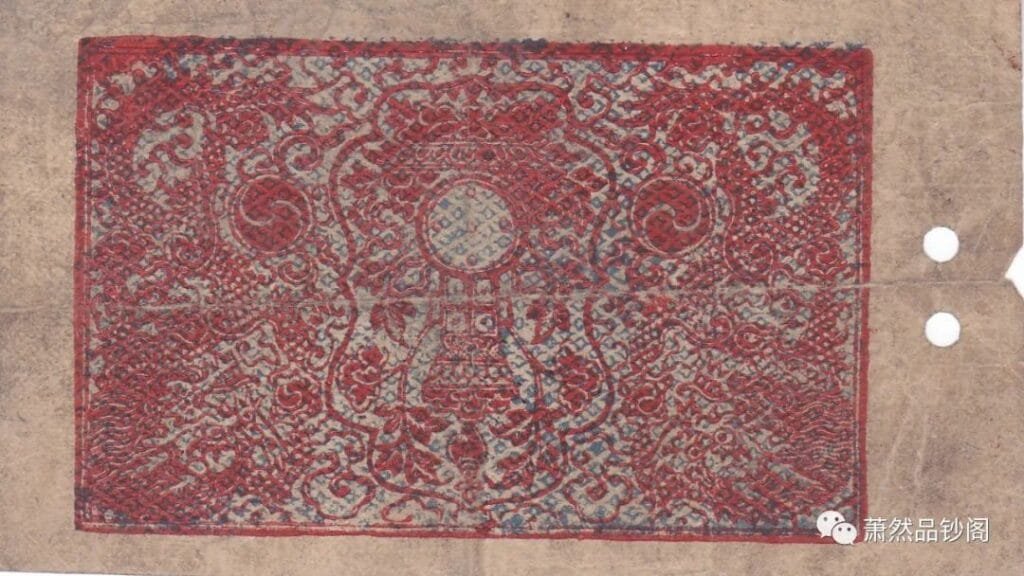

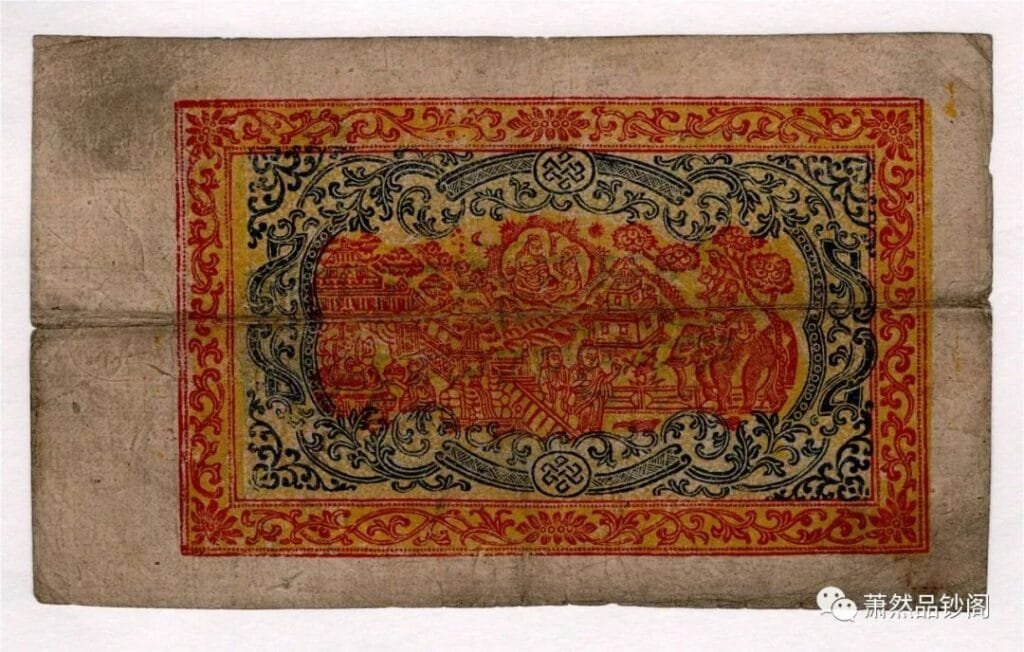

The reverse side of the 100 taels banknote showcases two saints seated beneath a lime tree, with symbolic imagery representing fertility, happiness, wealth, longevity, and prosperity. These elements, including a magical bottle, bats, cranes, and deer, convey the prosperity and blessings associated with Tibetan culture and tradition.

Preservation of Cultural Heritage

The accumulation of Tibetan silver notes has become a significant event in the annals of Tibetan currency distribution. Once concealed, these notes have transformed into cherished artifacts, akin to painted picture scrolls, embodying the legacy and traditions of Tibet. As both a form of currency and a work of art, Tibetan silver notes serve as a testament to the rich cultural heritage and artistic prowess of the Tibetan people.

I don’t know, how but I know somewhere my one of family members can be part of it. Actually I have got two pairs of note, what I get it I want to know?