In the mid-17th century, the rise of the Ganden Phodrang government marked a turning point in Tibet’s political and cultural history. Tibet entered a period of centralized administration led by the Dalai lama institution.

Amid this transformation, one issue drew immediate attention — the lack of standardized official clothing. During major ceremonies, Tibetan and Mongolian officials appeared in wildly different garments, creating a scene that seemed disorganized and inconsistent with the dignity of state ritual.

Recognizing the symbolic power of dress in governance, the Fifth Dalai Lama initiated one of the most important reforms in Tibetan ceremonial culture.

A Vision for Order: Reform Led by the Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso

The Fifth Dalai Lama believed that official attire reflected political legitimacy and social hierarchy. Troubled by the chaotic mix of styles at court, he commissioned his regent, Lobsang Tseten, to conduct a comprehensive study of historical garments and redesign a unified system.

On the 20th day of the 12th Tibetan month in 1672, the Dalai Lama recorded a detailed reflection on the philosophy, symbolism, and evolution of Tibetan dress. His writings reveal that clothing was never merely decorative — it was a visual language communicating authority, lineage, and spiritual alignment.

Aristocratic Society and the Culture of Adornment

In traditional Tibet, secular nobles were known as “Gar,” and were divided into three primary categories:

- Inner noble families

- Outer noble families

- Merit-based noble lineages

Jewelry and ornamentation played a crucial role in defining status. Historical accounts suggest that turquoise earrings became fashionable as early as the era of Songtsen Gampo and Trisong Detsen, reflecting both wealth and spiritual protection.

Turquoise was believed to attract powerful guardian deities — including mountain gods and protector spirits — making it more than an accessory; it was considered a shield of divine favor.

Gold ornaments, long earrings, red-and-white prayer beads, ceremonial hats, and tailored uniforms gradually became staples of elite fashion.

Foreign Influence and Imperial Connections

Tibetan dress traditions evolved through contact with expanding empires. After the rise of Genghis Khan and subsequent Mongol authority across Asia, Tibet entered a new geopolitical landscape.

Later, Kublai Khan granted authority over three Tibetan regions to the revered Sakya hierarch Drogon Chogyal Phagpa. This era introduced administrative ranks, ceremonial hats, and court attire suitable for high society.

Distinctive garments emerged alongside structured government offices, reinforcing class identity while aligning Tibetan governance with broader imperial systems.

Decline of Old Customs and the Search for Authentic Tradition

Over time, political fragmentation weakened many aristocratic traditions. Following upheavals in the 1640s, some ceremonial practices faded into symbolic existence rather than everyday reality.

The Mongol leader Gushi Khan — instrumental in establishing Gelug political authority — reportedly had little familiarity with these older customs. Yet when scholars explained their cultural meaning, he showed openness toward preserving them.

Because knowledge of traditional attire had grown scarce, experts were summoned to reconstruct authentic styles. Research revealed regional variations:

- In Nedong and Lhatse areas, structured uniforms were still used.

- In Shigatse and Gyantse, blue shawls often replaced formal robes.

This comparative study laid the foundation for a standardized ceremonial wardrobe.

The Birth of the “Treasure Robe” at the Potala Palace

Officials ultimately identified thirty categories of ornaments for court functionaries such as incense bearers, stewards, masters of ceremony, and reception officers.

On the second day of the first Tibetan month in 1672, the newly standardized “Treasure Robe” (Rinchen Gyancha)—inspired by earlier traditions of the Phagmodrupa Dynasty—was officially introduced during the New Year celebration at the Potala Palace.

Each ceremonial outfit was extremely valuable. When not in use, the robes were kept safely in the palace treasury and only brought out before the Tibetan New Year. Nobles who borrowed them had to record every jewel and carefully return each item after the celebrations.

This tradition highlighted not only the great financial value of the garments but also their deep symbolic and ceremonial importance.

The Prince Costume: Mandatory Dress of Secular Nobility

While the Treasure Robe appeared only once a year, the Prince Costume became essential formal wear for secular aristocrats under the Ganden Phodrang administration.

Nobles were required to wear it when:

- Paying audience to the Dalai Lama

- Attending major religious ceremonies

- Participating in state celebrations

The tradition endured until 1959, when Tibet’s Ganden Phodrang government came to an end.

Over time, subtle changes emerged. To showcase wealth and influence, some noble families replaced traditional woolen fabrics with luxurious silk — transforming ceremonial clothing into a powerful statement of prestige.

Imperial Titles and Rank-Based Dress

Another defining feature of the period was the introduction of honors granted by Dalai lama. Officials were expected to wear attire reflecting their rank, including plumed hats and embroidered insignia.

Meanwhile:

- Gushi Khan received recognition as King

- Sangye Gyatso was later appointed regent

- Tibetan leaders such as Polhané Sönam Topgyé rose through noble ranks.

Interestingly, Tibetan elites did not adopt Qing court dress. They prefer balance between honorary recognition and local cultural identity.

Clothing as a Mirror of Power, Faith, and Identity

The evolution of official dress in Tibet illustrates how clothing functioned far beyond aesthetics. It defined hierarchy, conveyed political legitimacy, and expressed spiritual values.

From turquoise earrings believed to attract protective deities to jewel-encrusted ceremonial robes guarded within palace treasuries, every detail told a story about authority and belonging.

These garments were not simply worn — they were performed, displayed, and revered, forming a visible framework through which society understood order and prestige in early modern Tibet.

Tibetan Noble and Official Dress in the Panden Phodrang Era:

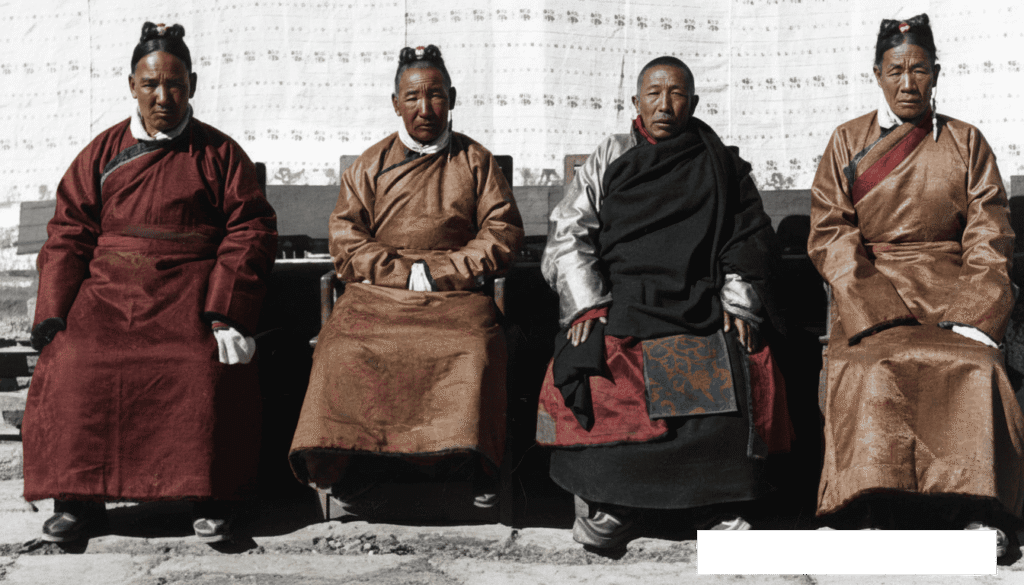

During the height of the Ganden Phodrang dynasty, Tibet developed a remarkably detailed system of ceremonial clothing that reflected political hierarchy, imperial recognition, and aristocratic prestige. Historical records provide vivid descriptions of how nobles and officials dressed for daily life and grand celebrations—revealing a society where attire functioned as a visible language of authority.

Among the most fascinating examples is the festival wardrobe of Polhané Sönam Topgyé, whose garments embodied both Tibetan tradition and foreign influence.

The Festival Attire of Prince Polhané

Official chronicles describe Polhané’s clothing with extraordinary precision, highlighting how seasonal dress balanced practicality with prestige.

Winter Elegance

In winter, the prince wore hats crafted from black or red fox fur, often lined with silk or satin for insulation and refinement. These luxurious materials not only protected against Tibet’s harsh climate but also signaled noble rank.

Summer Formal Style

During warmer months, he adopted a tall cotton cap modeled after autumn designs:

- Approximately 6–7 inches high

- Flat-topped with silk tassels

- Rolled brim about two inches wide

- Slits on both sides for comfort

- Trimmed with narrow otter fur

The result was both functional and visually commanding—ideal for public appearances.

Everyday Noble Clothing: The Chuba Robe

For daily wear, Polhané dressed in a high-collared robe known as the Chuba, typically made from multicolored brocade and lined with animal skins.

Key features included:

- Large collar without side slits

- Narrow sleeves for mobility

- Rich five-colored fabrics

- Leather or fur lining for warmth

This combination of durability and luxury made the Chuba a defining garment of Tibetan aristocracy.

Grand Celebration Dress: Power Woven into Fabric

During major festivals, the prince’s attire became even more elaborate.

He appeared in:

- A dragon-patterned robe

- A sable shawl draped across the shoulders

- A gold silk belt wrapped twice around the waist

- A knife pouch and purse

- A personal bowl bag, considered essential

- Fragrant leather boots

His hair was worn long, with a pearl earring adorning the left ear. Even his horse carried decorated chest ornaments—demonstrating that noble identity extended beyond the individual to every aspect of presentation.

Gawu and Coral Finials: Marks of Imperial Favor

As Ganden Phodrang authority deepened across Tibet, secular and monastic officials who received noble titles—such as duke, taiji, and zasak—were required to wear Gawu and jewel-topped hats corresponding to their rank.

One of the earliest Tibetans granted this distinction was Langjé Tseden, nephew of the scholar Doring Tenzin Paljor. In 1728, after the Gyantse campaign, Polhané award Langjé Tseden:

- First-class Taiji title

- Coral hat finial

- Peacock feather

Half a century later, in 1778, the Dalai Lama honored Doring Pandita for military achievements with a ruby finial and feather—an event so rare that crowds gathered throughout Lhasa to witness the spectacle.

Over time, representatives from prominent noble houses and relatives of successive Dalai Lama incarnations also received similar decorations, reinforcing their lineage and prestige.

These treasured insignia were typically stored in family vaults and worn only during major ceremonies, serving as powerful reminders of ancestral honor.

A Mature Dress System Under the Ganden Phodrang Government

After more than two centuries, the Ganden Phodrang established a comprehensive dress code governing both monastic and secular officials.

High-Ranking Secular Officials

Officials of the fourth rank and above—including silön, kalön, taiji, and zasak—were required to attend ceremonies in richly patterned satin robes featuring cloud and dragon motifs.

Their formal appearance included:

- Dragon roundel robes symbolizing authority

- Red embroidered boots with cloud designs

- Red-tasseled summer hats

- Fox-fur winter hats

Color itself signaled rank:

| Rank | Robe Color |

|---|---|

| Senior fourth rank | Bright yellow satin |

| Junior fourth rank | Purple-red satin |

| Fifth rank | Purple satin |

| Sixth–seventh ranks | Red wool |

Wearing colors beyond one’s status was considered a serious breach of protocol.

Noblewomen and the Art of Aristocratic Hairdressing

Elite women in Lhasa also reflected hierarchy through meticulous styling.

Their hair was arranged into structured buns, often prepared by professional hairdressers working in the city streets. Adornments were highly regulated:

- Hexagonal golden Buddhist reliquary boxes attached to the bun

- Rank-indicating jewels

For example:

- Third-rank ministers used red coral

- Taiji and zasak wore ruby ornaments

- Fourth-rank officials displayed turquoise

- Lower ranks used sapphire

These visual markers allowed observers to instantly recognize social standing.

Dress Codes for Monastic Officials

Monastic administrators followed equally strict clothing traditions.

Typical attire included:

- Yellow satin shirts

- Red sleeveless vests

- Monastic skirts

- Kasaya robes

- Brocade-edged garments

- Decorative red fabric panels on sleeves

Officials above the third rank were permitted to wear satin overcoats—garments once granted exclusively by imperial decree. Those honored with such robes were known as “lama of distinction,” signaling both religious authority and political recognition.

The Seasonal Changing Ceremony

Uniformity extended even to the calendar. Historically, all officials participated in biannual wardrobe transitions:

- Eighth day of the third Tibetan month: change into summer attire

- Twenty-fifth day of the tenth month: adopt winter garments

This occasion, often called the Changing of Dress Festival, was marked by formal ceremonies that reinforced discipline, hierarchy, and collective identity within the Tibetan administration.