Tibetan Palace Architecture: Site Selection, Sacred Landscapes, and Palace Layout

Tibetan palace architecture reflects a unique balance between strategic defense, religious belief, and harmony with nature. From ancient royal fortresses to spiritual centers like the Potala Palace, the placement and layout of Tibetan palaces reveal how geography, politics, and faith shaped architectural decisions across the Tibetan Plateau.

Choosing a Site for Palace Construction in Tibet

Strategic Location and Natural Defense

One of the defining features of Tibetan palace architecture is careful site selection. Palaces were commonly built on hilltops or mountain slopes within river valleys, offering commanding views and strong natural defenses. Steep cliffs, narrow access paths, and surrounding mountains helped protect royal residences from potential invasions.

A classic example is Yungbulakang Palace, located on Tashi Tsere Hill in the Yarlung Valley of southern Tibet. The palace is shielded by steep cliffs on its southeast side, while the gentler northern slope can only be reached by a narrow horse trail. This design made the palace highly defensible while maintaining control over the surrounding valley.

Similarly, the ruins of the Guge Kingdom were constructed on a mountain plateau oriented north to south and enclosed by two mountain ranges. This elevated position strengthened both security and visibility, reinforcing the strategic importance of high-ground palace construction.

Fortified Palaces and Defensive Infrastructure

Some Tibetan palaces combined strategic placement with man-made defenses. The Gongtang Royal Palace, built in the 11th century, was constructed at the base of a mountain resembling a hanging curtain. It was surrounded by defensive walls and moats, providing layered protection against external threats.

The Nêdong Official Residence also reflects this defensive mindset. Located on a horseshoe-shaped hill along the Yarlung River, the site offers a panoramic view of the valley below. The curved hill formation functioned as a natural fortress, enhancing surveillance and security.

Religious and Spiritual Factors in Palace Site Selection

Sacred Geography and Royal Devotion

Beyond military strategy, religious belief and spiritual symbolism played an essential role in choosing palace sites. Tibetan kings often selected locations with sacred associations, believing that the land itself held spiritual power.

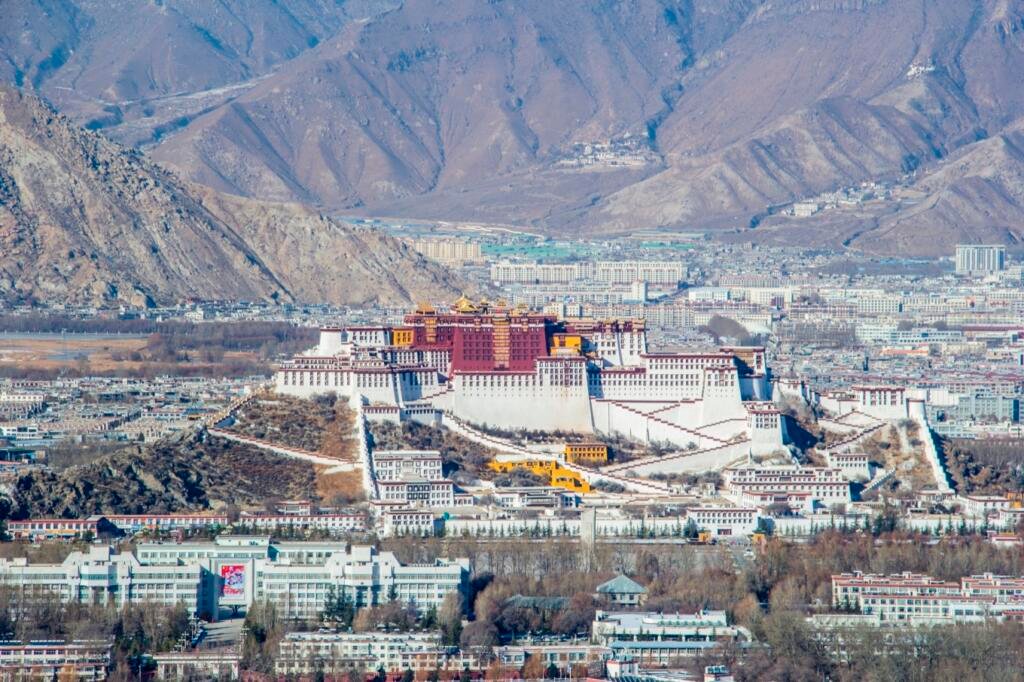

The construction of the Potala Palace in Lhasa is the most prominent example. King Songtsen Gampo chose Red Hill not only for its commanding position over the Lhasa Valley but also for its spiritual significance. According to The Records of Tibetan Kings, the king selected this site after deep contemplation, following the spiritual path of his ancestor Lhatototori Nyentsen, regarded as an incarnation of Samantabhadra.

This combination of royal authority and spiritual practice transformed the Potala Palace into both a political center and a sacred landmark.

Palace Architecture Layout and Spatial Design

Adapting to Mountainous Terrain

Tibetan palaces were designed to blend seamlessly with rugged landscapes. Rather than following rigid geometric plans, palace layouts often evolved organically, adapting to the shape of mountains, ridges, and valleys.

In large palace complexes, the main palace building is usually positioned at the highest point, symbolizing power and spiritual authority. Surrounding it are supporting structures such as temples, storehouses, workshops, and stables, arranged around one or more courtyards.

Courtyards and Orientation

Courtyards serve as important communal spaces for religious ceremonies, festivals, and daily activities. In keeping with Tibetan cultural beliefs, major buildings typically face south, a direction associated with warmth, light, and auspicious energy.

Lagyari Palace: A Model of Defensive Layout

The Lhagyari royal Palace in southern Tibet offers a clear example of traditional palace layout. Built on a high plateau overlooking the Seky River Valley, the palace complex includes both old and new sections.

The newer section is organized around a central square courtyard, enclosed by high defensive walls. Within this area stand the Ganden Lhagyari royal palace, temples, and auxiliary buildings. The courtyard measures approximately 80 meters east–west and 40 meters north–south and is decorated with blue and white stone patterns forming religious symbols, enhancing both aesthetic and spiritual significance.

Shol Village and Service Areas of Tibetan Palaces

Functional Spaces Beyond the Main Palace

Below the main palace complexes, many Tibetan palaces included a Shol Village or service settlement. These areas housed essential support facilities such as granaries, prisons, scripture printing houses, and living quarters for monks, officials, and palace staff.

The layout of Shol Villages was usually more flexible and organic, shaped by daily needs rather than strict planning. This practical arrangement allowed palace operations to function smoothly without disrupting the sanctity of the main royal and religious structures.

Shol Town of the Potala Palace

The Shol Town at the base of the Potala Palace in Lhasa follows a similar pattern. Administrative buildings and service quarters are clustered around the palace but remain loosely arranged, reflecting the Tibetan preference for adapting architecture to natural terrain rather than imposing strict order.

The Summer Palace: Seasonal Retreats in Tibetan Palace Architecture

In Tibetan palace architecture, Summer Palaces were often built at the foot of mountains or in nearby green valleys. These seasonal residences provided rulers and spiritual leaders with spaces for rest, leisure, and spiritual reflection, away from the harsher conditions of high-altitude hilltop palaces.

The most famous example is Norbulingka, the Summer Palace of the Potala Palace, located about 1.5 kilometers southwest of the Potala in Lhasa. Surrounded by expansive gardens known as Lingka, Norbulingka functioned as a peaceful retreat where the Dalai Lama could relax, meditate, and receive guests. The landscaped gardens, water features, and open courtyards reflect a softer architectural style focused on comfort and harmony with nature.

A similar pattern can be seen at the Lhagyari Royal Palace, whose Summer Palace lies on flat land to the north of the main palace. Enclosed by cliffs, this site offered a tranquil environment. Remnants of palace buildings and bathing pools are still visible today, highlighting the importance of wellness and seasonal living in Tibetan royal life.

Integration of Palaces and Monasteries

A Unified Secular and Religious Space

Many Tibetan palaces were built within or alongside major monasteries, reflecting the close relationship between political authority and religious power. These palace structures were often physically connected to monastic complexes, yet they maintained functional independence.

The Ganden Podrang at Drepung Monastery is a prime example. Located in the southwest corner of the monastery, the palace is carefully arranged along natural roads and streams, respecting the surrounding terrain rather than reshaping it.

Architectural Layout of Ganden Podrang

The Ganden Podrang palace features front, middle, and rear courtyards, with the main palace building positioned at the center. The four-story structure places the Dalai Lama’s living quarters on the top floor, symbolizing spiritual elevation. Lower floors contain administrative offices, religious halls, and meeting spaces, illustrating how governance and religious practice coexisted within the same architectural framework.

This organic integration of palace and monastery is a defining feature of Tibetan architectural design, where spiritual authority and political governance function within a shared sacred landscape.

Core Functions of Tibetan Palace Architecture

Tibetan palaces were multi-functional complexes, serving practical, symbolic, and spiritual purposes. Their roles evolved over time, especially as Tibet developed into a theocratic society.

Residence and Governance

Early Tibetan palaces functioned primarily as royal residences and political centers. Historical records from as early as 695 AD mention Tibetan kings (Tsenpo) residing in Tzama, an important political hub.

King Tride Tsukden frequently stayed at Wombu Garden in Tzama, where he hosted envoys from the Tang Dynasty, Arabia, Tujue (Turkic tribes), and Nanzhao. These palaces acted as centers of diplomacy and statecraft. Princess Jincheng, a key figure in Tibetan–Chinese relations, also lived at Tzama, reinforcing the palace’s political and ceremonial significance.

By 700 AD, records show Trimalo, the royal mother, hosting ministers at Wenjiang Duo Palace, further highlighting the palace’s role in administration and governance.

Religion increasingly became intertwined with politics. During the Qingshui Alliance of 783 AD between the Tang Dynasty and Tubo, the oath was sworn in a Buddhist tent, demonstrating how Buddhism was used to legitimise political authority and diplomatic agreements.

Religious Worship and Palace–Monastery Evolution

As Tibetan society became more theocratic, palaces increasingly incorporated religious spaces. Early palaces, such as those in the Guge Kingdom, contained only a few Buddhist worship buildings. Over time, these evolved into palace–monastery complexes, merging spiritual and secular authority.

The Potala Palace represents the height of this integration. Its Red Palace functions as the religious heart of the complex, housing major temples, stupas, and memorial halls. It serves as a site for religious rituals, political ceremonies, and commemorations.

The White Palace, by contrast, fulfills administrative and residential roles. It contains the Dalai Lama’s living quarters, government offices, and halls used for meetings and public audiences. Together, the Red and White Palaces embody the dual spiritual and political leadership at the core of Tibetan governance.

Defensive Role of Tibetan Palaces

Strategic Locations and Natural Barriers

Defense was a fundamental consideration in Tibetan palace construction. Most palaces were built on mountain peaks or ridges, using steep cliffs and rugged terrain as natural fortifications.

Notable examples include Yungbulakang Palace on Tashi Tsere Mountain, Trandruk Palace on Trandruk Mountain, and the Potala Palace on Red Hill. These elevated sites provided visibility, control over surrounding valleys, and strong protection against invasion.

Walls, Moats, and Complex Layouts

In addition to natural defenses, Tibetan palaces often featured thick walls, gates, and moats. The Potala Palace, for example, is encircled by strong defensive walls enclosing Shol City, which controlled access and protected both royal and religious residents.

The labyrinth-like internal layouts of Tibetan palaces further enhanced security, making them difficult to navigate for outsiders while reinforcing the authority and privacy of the ruling elite.

Types and Characteristics of Tibetan Palaces

Tibetan palaces share several defining architectural characteristics shaped by geography, religion, and governance:

- Defensive Design: Hilltop locations, thick walls, gates, and moats ensure protection and dominance over the landscape.

- Religious Integration: Temples, shrines, and prayer halls are often embedded within palace complexes, reflecting the spiritual role of rulers.

- Administrative Centers: Palaces served as hubs for governance, diplomacy, taxation, and military organisation.

- Symbols of Power: Monumental scale, towering walls, and ornate decoration project both political authority and spiritual legitimacy.

Together, these elements make Tibetan palaces not only architectural achievements but also enduring symbols of Tibet’s unique fusion of religion, politics, and landscape.