The Rise of Tibet on the Silk Road

The Silk Road was more than a trade network connecting East and West. It was a vibrant corridor of cultural exchange, religion, and political power. Nestled along the northeastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau, Tibet played a crucial yet often overlooked role in the development of the Silk Road. Through strategic geography, military expansion, and religious influence, Tibet became deeply intertwined with Silk Road history for more than a thousand years.

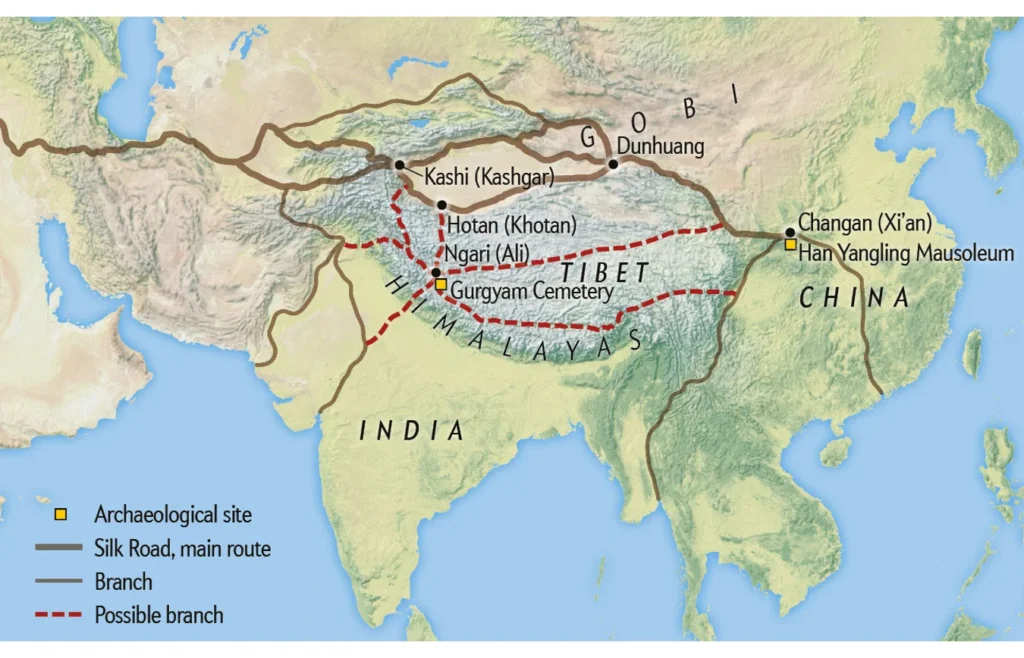

Among the many routes crossing the plateau, the Tuyuhun Route, also known as the Qinghai Route, passed through eastern Tibet and connected Central Asia with China’s interior. This route allowed early Tibetan ancestors, including the ancient Qiang people, to participate actively in Silk Road trade and cultural interactions long before the height of the Tibetan Empire.

Tibet and the Silk Road Before the Empire

Even before the rise of a unified Tibetan state, Tibetan and proto-Tibetan groups lived along key Silk Road corridors. Their position along highland passages enabled them to control movement between Central Asia, the Yellow River basin, and inland China. These early interactions laid the foundation for Tibet’s later political and cultural expansion along the Silk Road.

As trade increased, so did cultural exchange. Livestock products, medicinal herbs, salt, and textiles moved across the plateau, while ideas, beliefs, and technologies flowed in both directions.

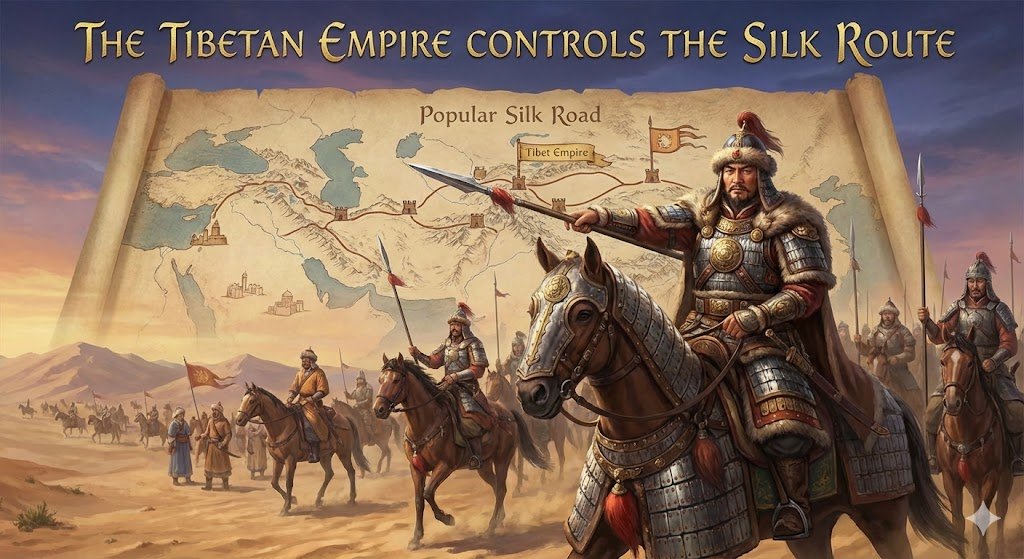

The Tibetan Empire and Control of Silk Road Routes

The relationship between Tibet and the Silk Road reached its peak during the Tibetan Empire (7th–9th centuries). In 633 AD, the Tibetan Empire conquered the Tuyuhun Kingdom, taking control of the Qinghai Lake region and securing the Tuyuhun Route. This marked Tibet’s formal entry into Silk Road geopolitics.

By 670 AD, Tibetan forces had captured the Anxi Four Garrisons, extending Tibetan influence over the southern Silk Road route. During the chaos of the An Lushan Rebellion, Tibetan armies occupied large parts of the Tang dynasty’s Western Regions, including major Silk Road cities such as Dunhuang, for nearly a century.

Tibetan administrators, soldiers, and civilians settled in these areas. Policies aimed at integrating local populations led to the spread of Tibetan language, customs, and religious practices. Even after the decline of Tibetan political control, Tibetan cultural elements remained deeply embedded in Silk Road communities.

Tibetan Presence During the Song and Yuan Dynasties

After the fall of the Tibetan Empire, Tibetans continued to live and trade along the Silk Road during the Song and Yuan dynasties. Large Tibetan populations settled in the Hexi Corridor, the Huangshui River basin, and the upper Wei River region.

In the Hexi Corridor, Tibetan tribes established the Liangzhou Six Valleys regime, which was later absorbed by the Western Xia. Meanwhile, the Qutang regime emerged in the Huangshui area and played an important role in protecting trade routes and facilitating commerce between Central Asia and China.

During this period, Xining (ancient Qingtang City) became a major Silk Road trading center, featuring dedicated districts for merchants from the Western Regions. Trade thrived, and Tibetan communities acted as intermediaries between different cultures and economies.

Eastward Expansion of Tibetan Buddhism

Compared with the imperial era, the Song and Yuan periods witnessed a dramatic eastward spread of Tibetan Buddhism. Rulers of the Western Xia and the Mongol Empire actively supported Tibetan Buddhist institutions, helping the religion flourish along the Silk Road.

Under the Yuan dynasty, Tibetan Buddhism became dominant in the Hexi region and beyond. Monasteries attracted followers from multiple ethnic groups, including Mongols, Tanguts, and Han Chinese. Tibetan Buddhist teachings, art, and rituals became a shared cultural framework across large sections of the Silk Road.

Tibetan Buddhism in the Ming and Qing Dynasties

During the Ming dynasty, the Chinese court adopted a supportive policy toward Tibetan Buddhism, recognizing its importance in maintaining stability along the northwestern frontier. Many Tibetan Buddhist monasteries were built in the Gansu–Qinghai region, often with imperial patronage.

These monasteries reflected a blend of Han and Tibetan architectural styles, symbolizing deep cultural integration. Tibetan Buddhism continued to serve as a bridge connecting different ethnic communities along the Silk Road.

In the Qing dynasty, Tibetan Buddhist influence declined along the main eastern Silk Road routes but remained strong along the edges of the Hexi Corridor, between the Qilian Mountains and Inner Mongolia. During the transition from Ming to Qing, the Oirat Mongols promoted Tibetan Buddhism by building monasteries, translating scriptures, and sponsoring religious education.

As a result, Tibetan Buddhism remained deeply rooted in the Western Regions, preserving religious diversity that continues into the present day.

Living Tibetan Communities Along the Silk Road

Today, Tibetan communities still thrive in parts of the Hexi Corridor and surrounding regions. Archaeological discoveries, ancient manuscripts, murals, and religious sites reveal the long-standing presence of Tibetan culture along the Silk Road.

Disciplines such as Dunhuang studies, Tibetan studies, and Western Xia studies have brought increasing academic attention to this heritage. These fields have uncovered valuable insights into how Tibetan culture interacted with trade, politics, and religion across centuries.

Tibetan Cultural Heritage and Academic Challenges

The material and spiritual heritage of Tibet along the Silk Road is vast, with some artifacts dating back thousands of years. Despite growing scholarly interest, research remains fragmented. Many studies focus on specific periods or locations, lacking a comprehensive view of Tibetan cultural development across the entire Silk Road network.

Another challenge lies in the limited number of scholars with deep training in Tibetan language and culture. Combined with scarce historical sources, this has made it difficult to fully understand Tibet’s long-term role on the Silk Road.

Given the wide geographic spread and long historical continuity of Tibetan culture, organizing existing research into a clearer framework helps reveal the depth and influence of Tibet’s presence along one of the world’s most important ancient trade routes.

Paper Documents: A Glimpse into Tibetan History Along the Silk Road

Paper manuscripts are among the most valuable witnesses to the cultural and religious exchanges that took place along the Silk Road. Tibetan documents, preserved across Central Asia and China, provide rare insights into governance, religion, daily life, and the spread of Tibetan Buddhism from the Tubo period onward. These texts reveal how Tibetan culture became deeply woven into the Silk Road world.

Tibetan Manuscripts from the Tubo Period in Dunhuang

The Dunhuang Mogao Grottoes are one of the world’s richest repositories of ancient manuscripts. Among the vast collection discovered there, Tibetan documents form the second-largest group, with estimates exceeding 10,000 scroll numbers. These manuscripts are now dispersed across countries including France, the United Kingdom, China, Russia, and Japan.

The collections acquired by Paul Pelliot and Aurel Stein are especially significant, containing a wide range of historical, administrative, legal, and religious texts. For nearly a century, these Tibetan manuscripts have remained a focal point of international academic research.

Joint efforts by institutions such as the Northwest University for Nationalities, Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House, the French National Library, and the British Library have led to systematic cataloging and publication. The French Collection of Dunhuang Tibetan Manuscripts has reached 16 volumes, while the British Collection of Dunhuang Western Regions Tibetan Documents has published six volumes. In China, over 90 percent of Dunhuang Tibetan manuscripts are preserved in Gansu, though many remain unpublished.

Digitization and New Research Directions

The International Dunhuang Project (IDP) has played a major role in preserving and sharing Tibetan Silk Road manuscripts. Complete digitization of the French Tibetan collection and a large portion of the British collection has made these materials accessible to scholars worldwide.

Recent archaeological discoveries within Tibet itself have uncovered Tubo-period Tibetan manuscripts similar to those found in Dunhuang. While earlier research focused mainly on secular documents such as contracts, laws, and economic records, scholarly attention is increasingly turning toward Buddhist manuscripts, opening new perspectives on Tibetan religious history along the Silk Road.

Tibetan Documents from the Western Regions

Thousands of Tibetan manuscripts originating from the Western Regions, including areas such as Khotan, are primarily preserved in the British Library. One of the most influential studies is Thomas’s Tibetan Documents and Manuscripts from Chinese Turkestan, which transcribed and analyzed 600 documents, making them available for the first time.

Japanese scholar Takeshi Watanabe further advanced the field with his work on ancient Tibetan social documents, published between 1997 and 1998. His research included facsimiles, detailed catalogs, and glossaries, significantly deepening understanding of Tibetan society in Central Asia.

Despite these efforts, many Tibetan manuscript fragments from the Western Regions remain unsorted and undigitized, representing a major opportunity for future Silk Road research.

Tibetan Script and Buddhism in the Western Xia Kingdom

Within the Western Xia Empire, Tibetan script was widely used alongside other writing systems. Tibetan Buddhist scriptures held high status and were officially mandated for monastic recitation, regardless of a monk’s ethnic background.

Excavations at Heishui City uncovered a remarkable collection of Tibetan documents now preserved in Russia, China, and the United Kingdom. The Russian collection alone contains over 300 pages, including manuscripts and woodblock prints believed to be among the earliest examples of Tibetan printing.

These texts display diverse formats such as Sanskrit-style folding, butterfly binding, and single-page amulets. Some Western Xia Buddhist texts include Tibetan annotations, demonstrating close interaction between Tibetan and Western Xia religious traditions.

Discoveries Across Gansu and Hexi Corridor Sites

Additional Tibetan manuscripts from the Western Xia period have been discovered at multiple sites across the Hexi Corridor. At Vajra Mother Cave in Wuwei, Tibetan documents were found alongside other religious materials. In Zhangyi Xiaoxigou, manuscripts and printed texts were uncovered in a Zen cave, while the Tiantishan Grottoes yielded Tibetan Buddhist scripture fragments carved into stone.

At Bingling Temple Grottoes in Yongjing County, ink-written Western Xia dharanis and a Tibetan dharani page were found, with the Tibetan text closely matching Western Xia versions. These discoveries highlight the shared ritual language and religious exchange along the Silk Road.

Legacy of Tibetan Documents from the Western Xia Period

Many Tibetan texts from the Western Xia era represent a continuation of Tubo-period traditions, while others reflect later Buddhist transmissions from central Tibet. Despite their importance, these materials have not yet been fully organized or systematically published, and academic research remains limited.

These documents demonstrate the deep integration of Tibetan Buddhism into Western Xia society and underscore Tibet’s lasting cultural influence along the Silk Road.

The Flourishing of Tibetan Buddhism in Later Dynasties

During the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties, Tibetan Buddhism flourished across Hexi and neighboring regions. Monasteries spread widely, and Tibetan manuscripts continued to circulate, even as many temples were later destroyed during periods of war and political upheaval.

Important collections survive in places such as Yongdeng, Gulang, and Yongchang, with the Wuwei Museum holding especially rich materials. Many manuscripts date to the Yuan and Ming periods and include dedicatory inscriptions and imperial era names, reflecting strong regional characteristics. Among the most remarkable finds is a Ming dynasty cinnabar-red printed Kangyur, though its original source remains uncertain.

Tibetan Manuscripts in the Mogao Grottoes

In the northern zone of the Mogao Grottoes, archaeologists discovered 115 Tibetan documents across 23 caves. These texts cover a wide range of subjects, including Buddhism, medicine, mathematics, and divination, dating from the Western Xia through the Yuan and Ming periods. They are now preserved at the Dunhuang Research Institute.

Tibetan Buddhism in the Qing Dynasty and Xinjiang

During the Qing dynasty, Tibetan Buddhism was widespread among the Oirat Mongols of Xinjiang, particularly under the Dzungar Khanate, which built large monasteries across the region. As a result, many Tibetan Buddhist manuscripts have been discovered in Xinjiang and are currently housed in institutions such as the Xinjiang Museum, though most remain uncataloged.

Recent Archaeological Discoveries

In 2014, stabilization work at Bingling Temple led to the discovery of nearly 1,000 pages of Tibetan Buddhist scripture fragments hidden within a cave. While their exact dating has yet to be determined, the find underscores how much Tibetan Silk Road material remains hidden and unexplored.

Tibetan Translations Along the Silk Road

Along the Silk Road, Tibetan Buddhist texts were translated into Western Xia, Uyghur, Chinese, and Mongolian, reflecting the widespread influence of Tibetan Buddhism across ethnic boundaries. Large numbers of Tibetan-to-Western Xia translations have been uncovered at Heishui City, Vajra Mother Cave, and the northern Mogao caves, now preserved in collections across China, Russia, and other countries.

These multilingual manuscripts vividly illustrate the role of Tibetan Buddhism as a unifying cultural force along the Silk Road and highlight the complex networks of translation, transmission, and belief that shaped Eurasian history.

Tibetan Inscriptions and Stone Carvings Along the Silk Road

Tibetan inscriptions and stone carvings form an important part of Silk Road cultural heritage. Their history can be traced back to the Tubo period, when the tradition of carving inscriptions on stone was influenced by practices from the Tang Dynasty. Although the total number of Tibetan stone inscriptions found along the Silk Road is relatively limited, their historical span is remarkable, extending from the early medieval period to modern times.

These inscriptions provide valuable evidence of political authority, religious devotion, artistic exchange, and the spread of Tibetan Buddhism across vast regions of Central and East Asia.

Tibetan Stone Inscriptions from the Tubo Period

Biantoukou Stone Buddha Temple Inscription

The Biantoukou Stone Buddha Temple Cliff, located in Minle County, Gansu Province, preserves an important Tibetan inscription dating to 806 AD. The site features carved Buddha images alongside Tibetan inscriptions, reflecting the strong connection between early Tibetan rule and Buddhist worship along the Silk Road.

Tubo Tomb Inscriptions in Dulan, Qinghai

In Dulan County, Qinghai, archaeologists excavated several Tubo-period tombs containing stone tablets. Four of these inscriptions clearly record the names of tomb owners, while six rectangular tablets were discovered in other tombs. One notable tablet bears the name of a Tubo queen, offering rare insight into royal burial practices and elite identity during the Tibetan Empire.

Skardu Inscription in Pakistan

The Skardu inscription, located in present-day Pakistan, also dates to the Tubo period. This inscription mainly contains prayers and auspicious wishes, highlighting the spiritual dimension of Tibetan inscriptions beyond administrative or commemorative purposes.

Stone Inscriptions from the Western Xia and Yuan Dynasties

Yuge Jun’s Testament Stone Tablet

Housed at Dafosi Temple in Xining, Qinghai, the Yuge Jun Testament Stone Tablet dates to the early 10th century. This inscription represents an early example of Tibetan cultural continuity following the decline of the Tibetan Empire.

Heishuiqiao Stone Inscription in Ganzhou

Also known as the Heihe Bridge Inscription, this important Western Xia stone tablet was erected in 1170 AD, during the seventh year of the Qianyou reign. Now preserved in Zhangye, Gansu, the inscription is bilingual, with Chinese text on the front and Tibetan text on the back. The two sides are believed to be direct translations of each other, offering valuable material for studying political communication and translation practices between cultures.

Mogao Grottoes Six-Syllable Mantra Inscription

Commissioned by Emperor Wenzong of the Yuan Dynasty in 1348 AD, this stone inscription is now preserved at the Dunhuang Research Institute. At its center is a depiction of the four-armed Guanyin Bodhisattva, surrounded by the Six-Syllable Mantra (Om Mani Padme Hum) carved horizontally in Tibetan script. Around the edges, the names of 95 donors are inscribed, reflecting widespread patronage of Tibetan Buddhism during the Yuan period.

Six-Syllable Mantra Stone Carvings Across the Silk Road

Stone carvings of the Six-Syllable Mantra are among the most widespread Tibetan inscriptions along the Silk Road. These carvings span multiple dynasties, including the Western Xia, Yuan, Ming, and Qing periods.

In Yongchang, Gansu, near Shengrong Temple, a remarkable Yuan Dynasty carving displays the mantra in six scripts: Chinese, Tibetan, Western Xia, Uyghur, Mongolian, and Brahmi. This multilingual inscription vividly illustrates the cultural diversity and religious inclusivity of the Silk Road.

In Qinghai, the Ganglong Stone Carving Site preserves Tibetan mantra inscriptions, while similar carvings have been found in Heishan, Dingxi, though their exact dates remain uncertain. Further south, in Xinjiang, sites such as Hongtuling and Zongkun’erma have yielded additional mantra carvings, demonstrating the wide geographic spread of Tibetan Buddhist devotion.

Ming Dynasty Tibetan Stone Inscriptions

Qutan Temple Stone Inscriptions in Qinghai

Qutan Temple, located in Ledu, Qinghai, was built with direct support from the Ming government. Originally, the temple contained seven stone inscriptions, most of which remain preserved today. These include imperial edicts issued during the Yongle, Hongxi, and Xuande reigns.

Each inscription features Chinese text on the front and Tibetan text on the back, offering invaluable evidence of Ming dynasty religious policy, bilingual administration, and official support for Tibetan Buddhism. These inscriptions also serve as key sources for studying translation practices between Chinese and Tibetan.

Dachongjiao Temple Inscriptions in Gansu

At Dachongjiao Temple in Minxian County, Gansu, the Imperial Inscription for the Four Great Pillars dating to the fourth year of the Xuande reign is preserved in a stone pavilion. Written in both Tibetan and Chinese, the inscription reflects the Ming court’s patronage of Tibetan Buddhist institutions and the integration of Tibetan religious communities into state governance.

Stone Inscriptions from Buddhist Sites in Gansu

Bai Ta Temple Restoration Inscription, Wuwei

An inscription commemorating the 1430 restoration of Bai Ta Temple in Wuwei records Ming dynasty support for Tibetan Buddhism. The temple was historically associated with Sakya Pandita, who lived and passed away there. The bilingual inscription, now kept by a local resident, provides insight into Tibetan religious influence in Hexi.

Guangshan Temple Restoration Inscription

The Guangshan Temple, also known as Rgya Yag Dgon, contains a Ming dynasty inscription dated to 1448. Written in both Chinese and Tibetan, it documents imperial patronage and the temple’s role as an important Tibetan Buddhist center in Wuwei.

Gan’en Temple Imperial Edict Inscription

The Gan’en Temple in Yongdeng County, Gansu, received its name through an imperial edict in 1525, during the Jiajing reign. The bilingual inscription reflects Ming dynasty religious governance and its engagement with Tibetan Buddhist leaders and local chieftains.

Tibetan Buddhist Cave Paintings Along the Silk Road

Cave Murals from the Tubo Period

During the Tubo period, Buddhist cave art flourished at major Silk Road sites such as the Mogao Caves and Yulin Caves. Approximately 56 caves at Mogao were excavated during Tibetan rule. While continuing earlier artistic traditions, these murals incorporated strong Tibetan elements, including depictions of Tubo rulers, officials, and protective deities.

Yulin Caves and Tang-Tubo Cultural Exchange

Cave 25 at the Yulin Caves contains an ancient Tibetan inscription confirming its Tubo-period origin. The murals inside depict both esoteric and exoteric Buddhist deities, as well as scenes of Tang–Tubo interaction, including wedding ceremonies and diplomatic exchanges.

The influence of Tubo Buddhist art extended beyond Dunhuang into regions such as Khotan and Kucha, where traces of Tibetan artistic styles appear in murals, sculptures, and literary sources. Despite growing scholarly interest, many aspects of Tubo Buddhist art along the Silk Road remain insufficiently studied, leaving important questions still open for future research.

The Flourishing of Tibetan Buddhism During the Western Xia Period

During the Western Xia period, Tibetan Buddhism inherited from the late Tubo era continued to thrive across regions such as Hexi, playing a crucial role in the revival of Buddhism within Tibet itself. As new Tibetan Buddhist sects emerged in central Tibet, they spread eastward along the Silk Road, reaching Hexi and even Xinjiang. This movement resulted in a dynamic fusion of older Tibetan traditions with new religious trends.

The Western Xia rulers adopted a policy of reverence and state support for Buddhism, allowing Tibetan Buddhism to flourish. Sacred sites, including the Mogao Caves, were carefully protected, and new caves were excavated, ensuring the continuity of Buddhist artistic and religious practices along the Silk Road.

Tibetan Buddhist Cave Art Along the Silk Road

Western Xia, Yuan, and Ming Cave Murals

Cave murals from the Western Xia, Yuan, and Ming dynasties display a striking blend of Han Chinese and Tibetan artistic styles, with a strong emphasis on Tibetan Esoteric Buddhism. Many caves contain mandalas, tantric deities, and ritual imagery unique to Vajrayana Buddhism.

Notable examples include Mogao Caves 206, 491, 398, 462, and 464, Yulin Caves 29, 2, and 3, as well as caves at Wufeng Temple. Scholars often regard Mogao Caves 462 and 464, along with the Northern Cave 77, as masterpieces of Tibetan Buddhist art from the Western Xia period.

Cave 465 stands out for its complex esoteric imagery depicting tantric practices and Indian tantric masters. Its dating remains debated, with scholars attributing it to either the Western Xia or the Yuan dynasty.

Murals in the Helan Mountains

In the Helan Mountains, the heartland of the Western Xia kingdom, Tibetan Buddhist murals have been discovered in sites such as Shanzuigou Cave. These murals depict Western Xia kings, Tibetan masters, and Buddhist deities, seamlessly blending Han and Tibetan religious iconography and artistic techniques.

Tibetan Buddhist Murals in Later Dynasties

During the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties, Tibetan Buddhist art continued to flourish in sites such as Matai Temple and Wenshu Temple in Sunan County, Gansu, and the Xumi Mountain Grottoes in Guyuan, Ningxia.

The Bingling Temple Grottoes in Yongjing County, Gansu, preserve Tibetan Buddhist murals from the Yuan through Qing periods, reflecting more than 800 years of uninterrupted Tibetan Buddhist dominance in the region. Along the Hexi Corridor, numerous temples have retained their original murals, showcasing refined artistic harmony between Han and Tibetan traditions.

Silk Paintings from the Tubo Period

Silk paintings unearthed from scripture caves represent the earliest known Tubo Buddhist paintings and are directly linked to the development of later Tibetan thangka art.

One notable example, S.P. 32. Ch. xxxvii004, is a tantric silk painting dated to 836 AD, created by the Tubo monk-painter Baiyang in collaboration with a Han Chinese artist. A Tibetan inscription records the dedication of the artwork, which includes depictions of the Medicine Buddha, Manjushri, Avalokiteshvara with a Thousand Hands and Eyes, Vaishravana, and Jambhala.

Other important Tubo silk paintings include E0.1148 housed at the Musée Guimet in France, along with works numbered S.P.160.Ch.00401, S.P.168.Ch.00377, and S.P.169.Ch.00376, all bearing Tibetan inscriptions and distinct Tubo characteristics.

Thangka Paintings from the Western Xia and Yuan Dynasties

Seven thangka paintings were excavated from the stupa in Cave No. 1 of Jinguang Haimu Cave in Wuwei and are now preserved in the Wuwei Museum. Among them, works such as “Bodhisattva Manjushri,” “Eleven-faced Avalokiteshvara,” and “Mahamayuri Vidyaraja with Vajravarahi and Mandala” are exceptionally well preserved.

The Manjushri thangka also portrays the Medicine Buddha, a Tibetan master, and a Western Xia official wearing a black hat and white robe. Its refined brushwork, vibrant colors, and fusion of Tibetan and Han artistic styles have earned it designation as a National First-Class Cultural Relic.

Additional thangka paintings were discovered at the Hongfota Pagoda in Helan County, Ningxia, the 108 Stupas of Qingtongxia, and the Baisikou twin pagodas, further illustrating the widespread influence of Tibetan Buddhist art.

Heishuicheng and Tibetan Buddhist Artifacts

More than 300 Buddhist paintings were excavated from the Heishuicheng Site in Ejina Banner, Inner Mongolia. Most were transported to Russia by Kozlov and are now housed in the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg.

In 2009, Northwest Minzu University, the Hermitage Museum, and Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House jointly published Russian–Tibetan Artifacts from Heishuicheng, marking the first systematic publication of these materials in China. These artworks prominently feature Tibetan Buddhist themes or a fusion of Han and Tibetan artistic traditions, occupying a central place in the history of Tibetan Buddhist art.

Architectural Remains from the Western Xia Period

The remaining base of a pagoda at Zamu Monastery in Wuwei features carvings of nine Buddhas arranged in two rows, separated by bead patterns, with a Tibetan inscription in the lower corner. The structure dates to the late Western Xia or early Yuan period.

The 108 Stupas of Qingtongxia, built in the style of Tibetan Buddhist lama stupas, have yielded numerous Tibetan Buddhist artifacts and are recognized as significant cultural heritage related to Tibetan Buddhism.

Architectural Remains from the Yuan Dynasty

The Saba Lingta site preserves the base of a monumental relic stupa built by Sakya Pandita after his death in Liangzhou (modern Wuwei). The structure remains well preserved and holds deep historical significance.

The Guazhou Zangmi Teda Tan Cheng site, discovered through aerial photography, is the largest outdoor mandala city of Tibetan Buddhism in China. Often referred to as the “First Mandala of Buddhism,” it remains one of the most mysterious and understudied sites along the Hexi Corridor.

Tibetan Buddhist Temple Architecture in the Ming and Qing Dynasties

Representative examples of Tibetan Buddhist architecture from the Ming and Qing periods include Qutan Monastery in Ledu, Qinghai, as well as Miaoyin, Gan’en, Ganzhong, and Dongda monasteries in Gansu. These temples reflect evolving layouts, decorative styles, and religious functions in northwest China.

The Dafosi Temple in Zhangye, originally a Tibetan Buddhist monastery from the Western Xia period, was later converted into a Han Buddhist temple. During the Yongle reign, it was renamed Hongren Temple. The earthen pagoda within the complex is a rare surviving Vajrayana-style lamaist stupa, making it one of the few of its kind in China.

Tombs and Burial Sites Along the Silk Road

Tubo Tombs in Dulan, Qinghai

The Dulan Tubo tombs, located along the Qinghai Route of the Silk Road, have yielded silk from the Central Plains, Central Asian brocades, gold and silver objects, Tibetan inscriptions, wooden slips, and stone sculptures. Although many tombs were damaged or looted, surviving artifacts now reside in museums in Qinghai, Gansu, Japan, the United States, and elsewhere.

While scholars debate whether these tombs belonged to the Tubo Empire or the Tuyuhun, the Tibetan inscriptions and wooden documents strongly indicate a Tubo cultural origin.

Tubo Tombs in Dachangling, Gansu

Another important burial site was discovered in Dachangling, Sunan County, in 1979. Excavations revealed 143 artifacts, including gold and silver vessels, woodblock prints of the twelve zodiac animals, and finely crafted ritual objects. These treasures are now housed in the Yugu Nationality Museum.