Who Is Shmashana Adhipati?

The Shmashana Adhipati is a fascinating and enigmatic figure in Himalayan and Tibetan traditions. The term “Shmashana” refers to a cremation ground, a sacred site associated with death, transformation, and ritual practices, while “Adhipati” signifies a lord or master. Together, they evoke the image of a deity or guardian who presides over these liminal spaces, symbolizing the cycle of life and death.

In Tibetan, this figure is known as Durkhrod Dakpo (དུར་ཁྲོད་བདག་པོ་), a key concept within certain tantric and esoteric practices. Often associated with fierce and wrathful deities, Shmashana Adhipati embodies the transcendence of fear and attachment, guiding practitioners to confront and overcome the impermanence and duality of existence.

Cultural Misinterpretations of Durdak

Shmashana Adhipati is frequently misidentified as the “Lord of the Charnel Grounds,” a term that conflates his symbolic role with that of other deities in Hindu and Buddhist traditions. This misunderstanding arises from superficial interpretations of iconography and texts, without considering the deeper ritual and philosophical meanings embedded within Tibetan Buddhism.

Unlike the Western notion of graveyards as places of mourning, cremation grounds in Tibetan and Indian traditions hold profound spiritual significance. They are seen as spaces for transcendence and liberation, where the physical body is returned to the elements, and the soul journeys onward. Shmashana Adhipati, as the master of these realms, serves as a powerful reminder of the fragility of life and the path toward enlightenment.

Symbolism and Iconography of Durdak

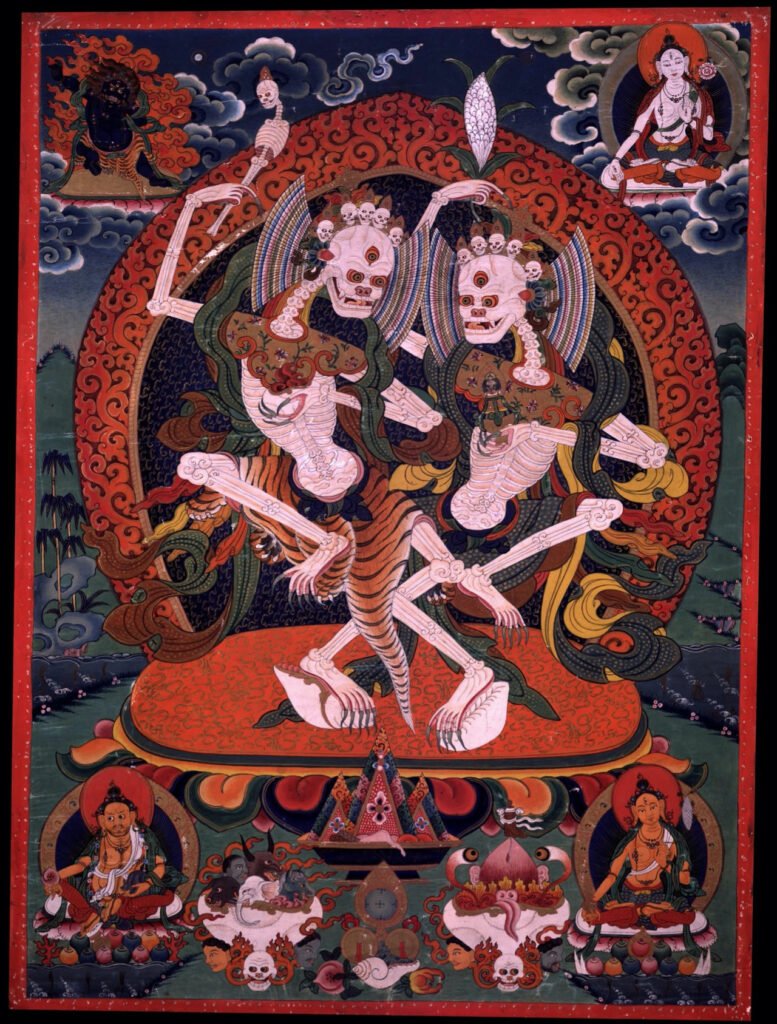

The visual depictions of Shmashana Adhipati are rich with symbolism, blending elements of wrath and compassion. Typically portrayed with fierce expressions and adorned with skulls or bones, these images are not meant to instill fear but rather to challenge perceptions and encourage a deeper understanding of life’s impermanence.

The snow-clad Himalayan region has embraced these forms within its artistic and cultural expressions, integrating them into a unique Tibetan aesthetic. The motifs of Shmashana Adhipati can often be found in sacred murals, thangka paintings, and ritual implements, each representing the interplay of life, death, and transcendence.

Who Are the Charnel Ground Lords?

In Tibetan, Durkhrod Dakpo (དུར་ཁྲོད་བདག་པོ་) translates to “Master of the Place Where Corpses Are Collected,” referring to the sacred cremation grounds central to Tibetan and South Asian esoteric practices. These figures come in two primary forms:

- The Parental Charnel Ground Lords (དུར་བདག་ཡབ་ཡུམ་), depicted as a divine couple.

- The Sibling Charnel Ground Lords (དུར་བདག་མིང་སྲིང་), portrayed as brother and sister.

Interestingly, in the South Asian cultural context, these identities are not mutually exclusive. The figures may simultaneously embody the roles of siblings and spouses, reflecting the intricate symbolic interplay in esoteric traditions.

Why the Dancing Skeletons?

The dance-like postures of these skeletal deities convey deep symbolic meaning:

- Celebration of impermanence: The dance represents the ephemeral nature of life and the ultimate unity of death and rebirth.

- Spiritual awakening: Through their dynamic movements, the skeletons remind practitioners to transcend attachment to the physical body and worldly concerns, embracing the path to liberation.

- Transformation and joy: Despite their macabre appearance, the dance of the skeletons symbolizes the joyous transcendence over fear, ignorance, and duality.

In the context of Tibetan ritual dances, these skeletal figures often serve as protectors and guides, leading participants to confront and embrace the truths of impermanence and spiritual transformation.

What Do Skeletal Deities Mean for the Living?

Far from being mere symbols of death, the skeletal deities hold profound significance for the living:

- Reflection of mortality: They remind us of the impermanence of life, encouraging a focus on spiritual growth and inner awakening.

- Guardians of wisdom: As masters of the cremation grounds, they embody spiritual wisdom, helping practitioners confront fears and illusions tied to physical existence.

- Path to liberation: By engaging with these symbols, practitioners are guided to overcome attachment and ignorance, paving the way for enlightenment.

Why “Charnel Ground Lord” Instead of “Lord of the Cremation Forest”?

The terminology matters when interpreting these figures. While many sources use terms like “Shitavana Adhipati” (Lord of the Cremation Forest), it is important to distinguish between the Sanskrit terms Shmashana and Shitavana:

- Shmashana: Refers to a platform or flat area designated for cremation, aligning with the Tibetan term དུར་ཁྲོད་ (dur khrod).

- Shitavana: Translates to “cool forest” (བསིལ་བའི་ཚལ་ in Tibetan), a location in ancient Magadha dedicated to corpse disposal, as described in Buddhist scriptures.

This distinction highlights the nuanced regional variations in the understanding and representation of cremation grounds, further emphasizing the need for accurate interpretation in Tibetan contexts.

Art and Symbolism of the Eight Charnel Grounds

In Buddhist art and esoteric practices, the Eight Charnel Grounds (དུར་ཁྲོད་ཆེན་པོ་བརྒྱད་, dur khrod chenpo gyé) hold significant symbolic meaning. While they are associated with terrifying and chaotic places, their concept differs from that of Durkhrod Dakpo (དུར་ཁྲོད་བདག་པོ་), or the Charnel Ground Lords, who preside over all realms of death and the intermediate state (bardo).

According to the explanations of Ju Mipham Rinpoche (འཇུ་མི་ཕམ་; 1846–1912), the Eight Charnel Grounds are distinct sites often described in esoteric teachings such as Hevajra and Chakrasamvara Tantras. These grounds are not merely places of corpse accumulation but chaotic, desolate landscapes identified by various features, including:

- Broken stupas

- Withered vegetation

- Piles of bones and decomposing bodies

These grounds are terrifying, dangerous, and symbolic of the practitioner’s confrontation with impermanence, fear, and the obstacles on the path to enlightenment.

The Eight Charnel Grounds and Their Guardians

Each of the Eight Charnel Grounds possesses unique characteristics and is guarded by fierce deities riding specific mounts. Below are the descriptions according to the Chakrasamvara Tantra:

- Eastern Violent Charnel Ground (གཏུམ་དྲག་, Gtum Drag):

- Guardian: Indra (དེར་དམ་帝释天), riding a white elephant.

- Symbolism: Represents aggression and destruction.

- Northern Dense Forest Charnel Ground (ཚང་ཚིང་འཁྲིགས་པ་, Tsang Tsing Thriks Pa):

- Guardian: Yaksha King riding a horse.

- Symbolism: The tangled, impenetrable nature of the mind.

- Western Flaming Charnel Ground (རྡོ་རྗེ་འབར་བ་, Dorje Barwa):

- Guardian: Varuna (婆罗那), riding a makara (mythical aquatic creature).

- Symbolism: Consuming flames, purification of impurities.

- Southern Bone-Lock Charnel Ground (ཀེར་རུས་ཅན་, Ker Rus Chen):

- Guardian: Yama (阎摩), riding a water buffalo.

- Symbolism: The unyielding grip of mortality and karmic bondage.

- Northeastern Laughing Charnel Ground (དྲག་ཏུ་རྒོད་པ་, Dragtu Godpa):

- Guardian: Ishana (伊舍那), riding a yellow ox.

- Symbolism: Frenzied laughter symbolizing chaos and dissolution.

- Southeastern Auspicious Fire Charnel Ground (མེར་བཀྲ་ཤིས་ཚལ་, Mer Tra Shis Tsal):

- Guardian: Agni (阿耆尼), riding a goat.

- Symbolism: Creative destruction and transformation through fire.

- Southwestern Gloomy Charnel Ground (མུན་པ་དྲག་པོ་, Munpa Dragpo):

- Guardian: Rakshasa King riding a corpse.

- Symbolism: Darkness and the mysteries of the unknown.

- Northwestern Howling Wind Charnel Ground (རླུང་དུ་ཀི་ལི་ཀི་ལི་, Lungdu Kili Kili):

- Guardian: Vayu (伐由), riding a Garuda (mythical bird).

- Symbolism: The fierce power of winds dispersing delusion.

The Role of the Charnel Grounds in Esoteric Practice

In the context of Vajrayana Buddhism, the Eight Charnel Grounds are more than physical or mythological locations. They serve as symbolic landscapes for profound spiritual transformation:

- Overcoming Fear: Practitioners confront their deepest fears and attachments.

- Symbol of Impermanence: The imagery of decaying bodies and barren landscapes underscores the transient nature of life.

- Integration of Dualities: The chaos and destruction of the charnel grounds reflect the integration of opposites—life and death, fear and courage, samsara and nirvana.

Distinguishing Shmashana and Shitavana

While the term Shmashana (དུར་ཁྲོད་) refers to cremation grounds or corpse disposal areas, Shitavana (བསིལ་བའི་ཚལ་, “cool forest”) specifically describes a cremation forest in ancient Magadha. The Tibetan texts often distinguish these terms, ensuring accurate interpretations of such symbolic places within tantric contexts.

Artistic Representations

In Tibetan art, the Eight Charnel Grounds are often depicted in mandalas or thangka paintings, forming the outer perimeter of the deity’s celestial palace. These artistic elements:

- Reflect the transformative journey through samsaric chaos.

- Act as meditative tools for practitioners visualizing their own spiritual path.

- Highlight the interdependence of destruction and creation in the quest for enlightenment.

Unveiling the Mystical Dance of the Skeleton Lords in Tibetan Buddhism

In the vibrant traditions of Tibetan Buddhism, two enigmatic figures often capture the imagination: the Shmashana Adhipati (Lord of the Cremation Grounds) and the skeleton dancers featured in ritual performances. While their appearances may seem similar, their roles and symbolism are distinct, shedding light on profound spiritual teachings and cultural heritage.

Who Are the Skeleton Dancers in Tibetan Rituals?

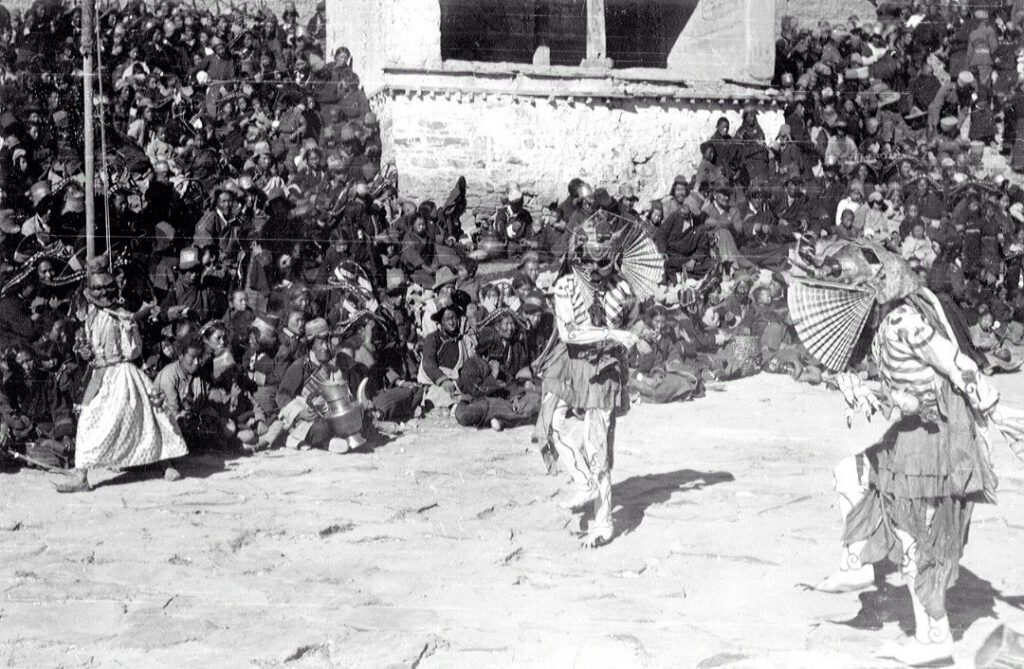

Skeleton dancers, often seen in the traditional Tibetan religious dances known as Cham (འཆམ་), play a pivotal role in ceremonial performances. These figures, adorned with vivid skeletal costumes, are not the main deities but serve as attendants or heralds, preparing the stage for the grand arrival of the primary deities.

In dances such as the Phurba Cham (Sacred Dagger Dance) or the Black Hat Cham, the skeleton dancers embody profound metaphors, symbolizing the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. Their rhythmic movements and striking visuals remind audiences of the impermanence of existence and the inevitability of transformation.

The Lord of Cremation Grounds: A Deity of Duality

The Shmashana Adhipati (translated in Tibetan as དུར་ཁྲོད་བདག་པོ་, “Lord of the Cremation Grounds”) is a powerful protector deity within Vajrayana Buddhism. Unlike the auxiliary skeleton dancers, this deity is revered as a guardian of sacred teachings, particularly those of Hevajra and Vajrayogini tantric traditions.

In South Asian traditions, Shmashana Adhipati is often identified with Shiva, the Lord of Destruction, and his consort Kali, who presides over cemeteries and cremation grounds. Stories recount Shiva meditating amidst ashes in burial grounds, using these desolate spaces to transcend earthly attachments. Similarly, in Tibetan Buddhism, the Lord of Cremation Grounds symbolizes mastery over death, guiding practitioners toward enlightenment by confronting impermanence.

Skeleton Lords in Cham Dances: Their Symbolism

In certain Cham dances, such as those centered around Phurba or Black Hat rituals, the skeleton dancers represent none other than the Shmashana Adhipati themselves. These figures take center stage, embodying profound spiritual lessons. Their skeletal forms remind onlookers of the transient nature of physical existence, while their energetic dance movements symbolize the cyclical nature of time and cosmic balance.

The skeleton dancers’ portrayal of both destruction and renewal highlights their dual role: confronting the fear of death while offering wisdom and liberation. This duality reflects the deeper teachings of Tibetan Buddhism, where impermanence becomes a gateway to spiritual awakening.

Key Insights into the Lord of Cremation Grounds

- Origins and Roles

- In South Asian traditions, the Shmashana Adhipati is associated with Shiva and Kali, embodying the raw power of destruction and creation.

- In Tibetan Vajrayana, the deity acts as a guardian of tantric teachings, particularly in the esoteric practices of Vajrayogini and Hevajra.

- Why the Cremation Grounds?

- Cremation grounds, with their stark confrontation of mortality, are seen as sacred spaces for meditation and spiritual realization.

- Skeleton Dancers vs. Shmashana Adhipati

- Skeleton dancers in Cham serve as symbolic attendants or reminders of life’s impermanence.

- The Shmashana Adhipati holds a deeper, divine role, embodying spiritual mastery over death and the transition to enlightenment.

Stay tuned as we delve further into the religious interpretations, artistic representations, and ritual significance of the Lord of Cremation Grounds in Tibetan culture. This mysterious figure offers profound insights into the spiritual depths of the Himalayan traditions.

The Legacy of Sakya Founders and the Practice of Shmashana Adhipati in Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism has a rich tapestry of deities and spiritual practices, and among these, the Shmashana Adhipati (Lord of the Cremation Grounds) holds a significant place, particularly in the Chakrasamvara Cycle (བདེ་མཆོག་རྒྱུད་). This tradition was notably introduced and developed in Tibet by Sachen Kunga Nyingpo (ས་ཆེན་ཀུན་དགའ་རྙིང་པོ་, 1092–1158), the first of the five founding patriarchs of the Sakya School.

Sachen Kunga Nyingpo: Spreading the Chakrasamvara Teachings

Sachen Kunga Nyingpo is regarded as the principal propagator of the Chakrasamvara Cycle in Tibet. His teachings established the foundational framework for the Shmashana Adhipati practices, which describe the role of the Lord of Cremation Grounds as both a protector of sacred wisdom and an aid to practitioners on their spiritual journey.

The Shmashana Adhipati in these teachings embodies the power to destroy worldly attachments, thereby allowing practitioners to transcend ordinary thought patterns and progress toward enlightenment. This profound system of practices was further elaborated by subsequent masters, particularly within the Ngor lineage (ངོར་རྒྱུད་) of the Sakya tradition.

The Role of Vajrayogini and Feminine Wisdom

While the Chakrasamvara Cycle forms the broader framework, Vajrayogini (རྡོ་རྗེ་རྣལ་འབྱོར་མ་) emerged as an independent practice system emphasizing the transformative power of feminine energy. Vajrayogini represents the feminine force of wisdom (prajna) and serves as a guide for practitioners on the tantric path. Over time, her practice significantly elevated the role of female energies and wisdom within Tibetan Buddhism.

The lineage of Vajrayogini is closely associated with the sky-dancer dakinis, who embody the enlightened feminine principle and inspire practitioners to embrace both emptiness and bliss in their meditative realizations.

Female Masters and the Cremation Grounds

One of the most remarkable figures in Tibetan Buddhism is Machik Labdron (མ་གཅིག་ལབ་སྒྲོན་, 1031–1129). Renowned as a great female Buddhist master, she devoted much of her practice to meditation in cremation grounds, visiting 108 such sites. Machik Labdron exemplified selfless compassion by offering her illusory body to the spirits and demons dwelling in these places, embodying the principles of fearlessness and detachment.

In certain Vajrayogini-Shmashana Adhipati texts, the female aspect of the Lord of Cremation Grounds (དུར་བདག་ཡུམ་) is given precedence over the male aspect (དུར་བདག་ཡབ་), highlighting the supremacy of feminine wisdom in spiritual practice. This shift underscores the evolving recognition of the importance of female figures and energies within Tibetan Buddhist philosophy and rituals.

Key Contributions of the Sakya Tradition

- Integration of Shmashana Adhipati Practices

- Sachen Kunga Nyingpo was instrumental in introducing these practices to Tibet, emphasizing their role in overcoming worldly delusions.

- Subsequent masters, such as Ngorchen Kunga Zangpo (ངོར་ཆེན་ཀུན་དགའ་བཟང་པོ་, 1382–1456), further cemented the Shmashana Adhipati as a key protector deity in the Sakya tradition.

- Elevation of Vajrayogini Practice

- Vajrayogini became a prominent figure representing feminine power and wisdom in tantric teachings.

- The teachings emphasized the transformative power of embracing both bliss and emptiness.

- Recognition of Female Masters

- Figures like Machik Labdron played a pivotal role in showcasing the strength and spiritual potential of women, contributing to the integration of feminine energy in Tibetan Buddhism.

The Legacy of the Cremation Grounds

The Lord of the Cremation Grounds and Vajrayogini continue to hold a central place in Tibetan Buddhist philosophy and practice. These figures challenge practitioners to confront impermanence, embrace wisdom, and transcend dualistic thought. From Sachen Kunga Nyingpo to Machik Labdron, their legacies shine as beacons of spiritual transformation in the rich tapestry of Tibetan Buddhism.

Chitipati in the Gelug Tradition: Evolution and Artistic Significance

The Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism, known for its structured monastic system and philosophical rigor, adapted the worship of the Lord of Cremation Grounds (Shmashana Adhipati) from the Sakya tradition. Under the leadership of key figures like the 6th Panchen Lama, Palden Yeshe (དཔལ་ལྡན་ཡེ་ཤེས་; 1738–1780), the Gelug school developed its unique interpretation of Shmashana Adhipati, often referred to by the name Chitipati (ས་ཕུང་བདག་པོ་, Lord of the Burial Mound)—a term that gained considerable popularity in the West.

6th Panchen Lama: Establishing the Gelug Chitipati

The 6th Panchen Lama introduced Chitipati as a central protector figure in the Gelug tradition. By adapting the Sakya perspectives and integrating them into Gelug philosophy, he emphasized Chitipati’s role as a guardian of spiritual treasures.

Unlike earlier interpretations, the Gelug Chitipati also came to symbolize the protection of material wealth, a shift that reflected the socio-political needs of the time. The deity’s imagery in Gelug art evolved to highlight this dual role, blending spiritual guardianship with material prosperity.

7th Panchen Lama: Expanding the Role of Chitipati

The 7th Panchen Lama, Tenpai Nyima (བསྟན་པའི་ཉི་མ་; 1782–1853), played a key role in further defining Chitipati’s function within the Gelug tradition. He expanded on his predecessor’s teachings by reinforcing the deity’s role as a wealth guardian, incorporating Yellow Jambhala (the deity of wealth) and other prosperity symbols into Chitipati’s artistic representations.

This emphasis on Chitipati’s role in safeguarding both spiritual and material resources ensured the deity’s growing prominence in the Gelug school’s pantheon.

Artistic Challenges in Depicting Chitipati

Traditional Tibetan artists faced unique challenges when illustrating Chitipati. The complexity of the deity’s form and symbolic elements required exceptional skill and creativity.

- Animating a Skeleton

- Chitipati is depicted as a skeletal figure engaged in a dynamic dance, embodying the transience of life and the inevitability of death. Artists had to convey motion and vitality in an otherwise static skeletal form, creating a sense of rhythm and grace.

- Expressive Eyes

- The eyes of Chitipati, often seen as hollow sockets, were painted with special attention to give them a sense of piercing focus and spiritual intensity, symbolizing the deity’s omniscient gaze.

- Ornamentation and Backgrounds

- The skeletal figure is adorned with elaborate jewelry, garlands of human skulls, and vibrant robes, all set against a richly detailed background that often includes cremation grounds, fire, and swirling smoke. These intricate elements symbolized Chitipati’s connection to the cycle of life, death, and rebirth.

Three Masterpieces of Chitipati Art

Here are three exceptional depictions of Chitipati that highlight the evolution of the deity’s significance and artistry:

- The Philosophical Transition

- This piece reflects the shift in religious philosophy from the Sakya to the Gelug tradition, with Chitipati depicted as both a spiritual protector and a symbol of material abundance.

- Early Masterpieces

- As an early depiction of Chitipati, this artwork stands out for its raw energy and dynamic composition, showcasing the deity in a vivid, almost surreal dance amidst the cremation grounds.

- Serendipitous Viewing Experience

- This unique painting captivates viewers with its combination of unusual color schemes and intricate details, creating an almost meditative experience that bridges artistic excellence with profound spiritual insight.

Legacy and Modern Appeal

The imagery of Chitipati continues to resonate, not only within Tibetan Buddhism but also among art enthusiasts and spiritual seekers worldwide. The deity’s dual role as a guardian of spiritual wisdom and material wealth offers a timeless reminder of the impermanence of life and the importance of balance in spiritual practice.

The Artistic Evolution of Chitipati: A Comparative Analysis

The depiction of Chitipati (Lord of Cremation Grounds) offers a profound insight into the philosophical and artistic evolution across Tibetan Buddhist traditions. From the minimalistic styles of the Sakya Ngor lineage to the wealth-associated interpretations of the Gelug tradition, these artworks encapsulate layers of symbolism, narrative, and spiritual practice. Below, we explore two significant works: one from the 15th-century Sakya Ngor lineage and another from the Gelug tradition with Mongolian influences.

1. Sakya Ngor Lineage: The Simplicity of Wisdom

This 15th-century masterpiece represents the Sakya Ngor lineage’s style, known for its clear spatial arrangement and minimalistic composition.

Key Features:

- Skeleton Palace:

The background depicts Chitipati’s skeleton palace (རུས་ཀྱི་ཕོ་བྲང་) with a canopy made entirely of skulls and curtains adorned with intricate mandala patterns (འཁོར་ལོའི་གེ་སར་). This design emphasizes the transcendence of life and death. - Three Eyes of Wisdom:

Chitipati is portrayed with a third eye, symbolizing an enlightened perspective that sees beyond the illusion of life and death. - Musical Symbols:

Beneath their feet lie a conch shell and other musical instruments, signifying the cosmic harmony that Chitipati embodies through their dance. - Skeleton Staff (རུས་རྐང་):

The skeletal staff in their hand represents their power to destroy all negative actions and obstacles to liberation. - Square Burial Ground Design:

The lower portion features two square spaces representing the cremation ground. This simplified layout reflects the Ngor lineage style, which influenced later Tibetan art schools, including the Khyenri School (མཁྱེན་རྩེའི་ལུགས་).

2. Gelug Interpretation: Wealth and Prosperity in Focus

The second artwork, though damaged, reflects the Gelug school’s reimagining of Chitipati, especially popular in Mongolian regions. Unlike the Sakya representation, the Gelug adaptation emphasizes Chitipati’s role as a guardian of wealth and fortune.

Key Features:

- Additions for Wealth Protection:

Chitipati is depicted holding a grain staff and a treasure vase, symbolizing their role as protectors of material wealth and spiritual prosperity. - Wealth Deities in the Composition:

Below the main figure, Yellow Jambhala (ཛམ་བྷཱ་ལྷ་) and Nourishing Wealth Goddess (ལྷ་མོ་ནོར་རྒྱུན་མ་) are included, reinforcing the connection between Chitipati and fortune. - Artistic Distress as Symbolism:

The damage to this artwork, while unfortunate, enhances its visual and thematic alignment with Chitipati’s nature. The blurred lines and faded elements create an ethereal atmosphere, evoking the transience of life and the interplay of reality and illusion.

Artistic and Philosophical Interpretations

Both works underscore the rich symbolic depth of Chitipati’s imagery:

- Sakya Ngor Perspective:

Focused on the impermanence of life and the spiritual liberation that comes from recognizing this truth. The simplicity of the design enhances the philosophical message. - Gelug Perspective:

Expands Chitipati’s role to include worldly concerns like wealth, reflecting the Gelug school’s broader engagement with practical aspects of life and society.

Visual Impact and Spiritual Reflection

The damaged Gelug artwork evokes a poignant spiritual reflection, reminding viewers of the impermanence of existence. The interplay of darkness, fire, and the skeletal form captures the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth. The blurred and weathered features create a dreamlike vision where immortality fades and fleeting moments gain clarity.

Conclusion: Chitipati as a Timeless Symbol

Through their dance, Chitipati bridges the realms of life and death, material and spiritual. These artistic representations, whether minimalist or intricate, offer profound reminders of impermanence, wisdom, and the path to liberation.