Before British forces advanced toward Tibet from colonial India, the overall situation inside Tibet was already extremely fragile. Politically, culturally, and economically, the country was facing serious internal challenges. Social thinking was deeply shaped by rigid conservatism and strong religious devotion, which often overshadowed critical reasoning and open engagement with the outside world.

At that time, Tibet avoided meaningful contact with foreign nations. Establishing diplomatic or trade relations was widely viewed with suspicion. Many believed that introducing foreign cultures or religions into Tibet would threaten its sacred Buddhist traditions and destroy its unique civilization. Similarly, spreading Tibetan culture abroad was not considered a priority. Isolation was seen as protection.

Historical accounts note that some parents even warned their children that using soap imported from India or eating foreign sweets could invite harmful foreign ideas and weaken the Dharma. Such narratives reflect the deep fear of cultural contamination that shaped public opinion.

Internal Political Tensions and Power Struggles

Beyond cultural isolation, Tibet also faced serious internal political conflicts. Competition for official positions among aristocratic families and high-ranking officials created instability within the government.

Modern historians often discuss the short lifespans of the 8th, 9th, 10th, and 11th Dalai Lamas, suggesting that internal political intrigue may have played a role. Even during the time of the 13th Dalai Lama, Ngawang Lobsang Thupten Gyatso, tensions within the regency system were significant. Historical records mention that Regent Demo Ngawang Lobsang Trinley Rabgye was accused of performing rituals against him, highlighting how deeply political rivalry had penetrated religious institutions.

These internal divisions weakened Tibet at a time when global powers were expanding across Asia.

The East India Company and British Interest in Tibet

By the 17th century, British commercial interests in India had grown rapidly. The East India Company, founded in London on December 31, 1600, became a powerful colonial enterprise. Its original goal was to dominate trade in spices and other valuable goods from India. Over time, it expanded its political and military influence across the Indian subcontinent.

According to The Fate of Tibet by Claude Arpi, the founding of the East India Company marked a turning point in British global expansion. British officials gradually began to consider Tibet not only as a potential trade partner but also as a strategically important region on the northern frontier of British India.

Although trade with Tibet was initially small, British administrators in Bengal believed that expanding commercial ties with Tibet could bring significant economic benefits. Precious metals, wool, salt, and medicinal goods were of particular interest.

At the same time, rumors of growing relations between Tibet and Russia increased British anxiety. If Russian influence expanded southward, it could threaten British control in India. This geopolitical rivalry—often described as part of the “Great Game”—motivated Britain to pursue contact with Tibet.

Tibetan Suspicion Toward Britain

Despite British interest, the Tibetan government remained cautious and largely unresponsive. Many Tibetans viewed Britain with deep suspicion.

Common people believed that if foreigners set foot on Tibetan soil, local deities might become angered, resulting in droughts, poor harvests, and social disorder. Among political and religious leaders, there were fears that engaging with Britain could lead to legal changes, foreign pressure, and ultimately the erosion of Tibetan culture.

Scholars from Sera Monastery and other major institutions reinforced these concerns. The so-called “Three Great Monasteries” of Lhasa—Sera Monastery, Drepung Monastery, and Ganden Monastery—reportedly urged the government to prevent foreign entry into Tibet. Official proclamations were issued across border regions to restrict foreign access.

As a result, many Tibetans believed that remaining isolated from Britain would best protect their religion and national identity.

Early Diplomatic Contacts: Myth and Reality

Some historians argue that early diplomatic exchanges between Tibet and Britain did occur. In 1774, the Panchen Lama initiated communication with Warren Hastings, the Governor-General of Bengal. This correspondence encouraged improved relations following conflicts involving Bhutan.

Taking this opportunity, Hastings sent George Bogle to Tibet. Bogle, accompanied by Dr. Alexander Hamilton, traveled to Shigatse and met the Panchen Lama in 1774. These meetings marked one of the first formal encounters between British representatives and Tibetan religious authorities.

However, this did not lead to sustained government-to-government diplomatic relations. After several months, the Tibetan authorities instructed the British delegation to return to India. No formal political treaty followed.

Later, in the late 19th century, the British sent the Bengali scholar-explorer Sarat Chandra Das to gather information about Tibet. With assistance from certain Tibetan figures, he traveled extensively and compiled valuable geographical and political data. When Tibetan authorities suspected espionage, Das fled back to India. Those who had assisted him reportedly faced severe punishment.

These incidents deepened Tibetan mistrust and reinforced the belief that foreign engagement posed serious risks.

Manchu Influence and Anti-Foreign Propaganda

During this period, the weakening authority of the Qing (Manchu) Empire also shaped Tibetan perceptions. As Qing power declined, there were efforts to strengthen influence inside Tibet. Propaganda spread the idea that allowing foreigners into Tibet would harm Buddhism.

Such messaging further intensified resistance to foreign contact. Religious institutions and political authorities alike promoted the defense of tradition against external threats.

Isolation as a Policy Choice

By the late 18th and 19th centuries, Tibet had largely chosen isolation as a strategy for survival. While Britain sought trade expansion and geopolitical security, Tibet prioritized cultural preservation and religious continuity.

Yet beneath the surface, both internal political fragility and external imperial pressures were steadily increasing, setting the stage for dramatic changes in the decades to follow.

Britain’s Expanding Strategy Around Tibet in the 19th Century

Although Britain had long tried various diplomatic methods to establish relations with Tibet, its strategy became more aggressive after consolidating power in India.

By 1849, the British had effectively secured control over large parts of the Indian subcontinent under the authority of the East India Company. After the mid-19th century, particularly following conflicts such as the Second Opium War, Britain expanded its influence deeper into Asia. Step by step, it began to view Tibet as a strategic frontier region.

Rather than attacking Tibet directly at first, British policy focused on surrounding Tibet by subduing its neighboring states.

The Nepal War and the Treaty of Sugauli (1815–1816)

One of the earliest examples was the Anglo-Nepalese War (1814–1816). In 1814, British forces clashed with Nepal, which bordered Tibet to the south. After intense fighting, Nepal was forced to sign the Treaty of Sugauli in 1816.

This treaty reduced Nepal’s territory and increased British influence in the Himalayan region. From a strategic perspective, controlling Nepal meant gaining leverage over a country directly connected to Tibet. As Tibetan sources later reflected, Britain’s repeated military interventions in Nepal were not random—they were closely linked to its long-term interest in Tibet.

At that time, Nepal reportedly sought assistance from the Qing amban (imperial resident) in Lhasa, but meaningful military support did not materialize. Ultimately, Nepal had to negotiate alone.

British Intervention in Bhutan (1864–1865)

Britain then turned its attention to Bhutan. Internal political conflicts within Bhutan in the early 1860s provided an opportunity for British intervention. After military confrontation, Bhutan was compelled to sign the Treaty of Sinchula in 1865.

Under this treaty, Bhutan ceded territories to Britain, including the Duars region, and accepted annual payments. Britain also secured influence over key trade routes and frontier zones. Locations such as Darjeeling became strategic footholds for British political and military operations near Tibet.

Tibetan authorities closely monitored these developments. The Kashag (Tibetan cabinet) and high religious institutions debated the implications. They concluded that if Britain gained transit access through Bhutan, Tibet’s southern defenses would be significantly weakened.

The Sikkim Question and British Pressure (1860s)

After Bhutan, British attention intensified toward Sikkim (Drémojong), another Himalayan kingdom bordering Tibet, Nepal, and Bhutan.

In 1863, British officials approached Sikkim’s leadership and proposed a 23-point agreement. Among the key conditions were:

- Prohibiting Sikkim from residing under Tibetan authority.

- Preventing the Tibetan government from interfering in Sikkim’s internal affairs.

- Expanding British political and commercial access.

By weakening Tibetan influence in Sikkim, Britain effectively removed a major buffer zone along Tibet’s southern frontier. Control over Sikkim allowed Britain to alter border dynamics and eliminate obstacles to future incursions.

The Chefoo (Yantai) Convention and Qing-British Negotiations

Another British strategy involved negotiating directly with the Qing Empire.

In 1876, during diplomatic discussions at Yantai (known in Western sources as Chefoo), Britain and the Qing government signed the Chefoo Convention.

According to records, the agreement allowed British subjects to travel between China and India via Tibet under certain conditions. Qing authorities even issued travel permits for British exploration parties to pass through Tibetan territory.

When news of this agreement reached Lhasa, Tibetan officials reacted strongly. They argued that Tibet had its own government and territorial authority, and that no foreign nationals—regardless of Qing approval—could enter Tibetan land without permission from the Tibetan government.

A large assembly was convened in Lhasa. It was declared that:

- Tibet retained sovereign authority over its territory.

- No foreigner could enter Tibetan soil without direct authorization.

- Any individual attempting entry without Tibetan approval would be stopped at the border, regardless of possessing Qing-issued documents.

Orders were issued to frontier dzongs (fortresses) and border officials to strictly enforce this policy.

Britain’s “Encirclement Before Penetration” Strategy

From Nepal to Bhutan and Sikkim, and through negotiations with the Qing court, Britain systematically reduced Tibet’s geopolitical buffer zones.

The pattern was clear:

- Subdue or influence Tibet’s neighboring Himalayan states.

- Secure trade routes and military footholds.

- Negotiate with imperial China to legitimize access.

- Increase pressure on Tibet from multiple directions.

Tibetan historical texts later described this strategy as a gradual removal of defensive barriers—clearing every obstacle before attempting deeper penetration.

By the late 19th century, Britain had positioned itself along much of Tibet’s southern frontier. While direct invasion had not yet occurred, the strategic groundwork had been laid. The stage was set for the dramatic confrontations that would unfold in the early 20th century.

Causes and Course of the Anglo-Tibetan Conflict (19th–Early 20th Century)

The roots of the Anglo-Tibetan conflict can be traced back to the mid-19th century, when British expansion in the Himalayan region began to directly affect Tibet’s southern frontier.

British Expansion into Bhutan (1863–1865)

In 1863 (Wood Ox Year of the 14th Rabjung cycle), Britain advanced into Bhutan, south of Tibet. After military pressure, Bhutan was forced to sign the unequal Treaty of Sinchula. As a result, territories such as the Duars were ceded, and Britain strengthened its frontier control.

At the same time, Britain consolidated its presence in strategic Himalayan locations, including Darjeeling and Kalimpong (Ka-bu), building roads, bridges, military depots, and intelligence offices. These developments clearly signaled long-term geopolitical ambitions.

Trade Demands and Tibetan Resistance

Britain sought to open a trade route into Tibet via the Chumbi Valley (Lungthur). However, the Tibetan government (Kashag) and the Qing amban in Lhasa repeatedly delayed or resisted formal agreements.

Officials such as the Regent Ngawang Palden Chokyi Gyaltsen (Reting lineage), Kashag ministers including Dokhar Tsering Norbu, Lobsang Yonten, and others, warned that British expansion was not merely commercial. They believed it threatened Tibet’s religious foundations and sovereignty.

Reports circulated that Britain was preparing for military action. In response, Tibetan authorities dispatched investigators, including Qing official Zhang Qingtong and Tibetan military commander Tashi Lingpa, to examine border conditions. Unfortunately, their mission failed to fully assess the real military preparations taking place in Sikkim and surrounding areas.

Sikkim as a British Base

Britain increasingly used Sikkim as a staging ground. Roads toward Tibet were improved, bridges constructed, and supply depots established. By the 1880s, Sikkim had effectively become a British-controlled buffer zone.

In 1883 (likely referring to the early 1880s period), Sikkim’s ruler Thutob Namgyal and Yeshe Dolma sought Tibetan protection under British pressure. Tibet received them respectfully and even provided financial assistance upon their return. This act further heightened British suspicion toward Tibet.

Tibetan National Mobilization

Facing mounting threats, Tibet convened multiple large assemblies. The consensus was firm:

- No British trade missions would be accepted.

- No foreigner would be allowed to cross into Tibetan territory.

- Defensive preparations must be intensified.

A binding national oath was proclaimed. Troops were mobilized from Ü-Tsang, Lhoka, Kongpo, Powo, Kham, and northern nomadic regions. If necessary, monastic forces would also be recruited.

Weapons—including locally made cannons, matchlock rifles, gunpowder, arrows, spears, and even stones—were gathered. Grain supplies and transport logistics were organized without delay.

Major monasteries such as Sera Monastery, Drepung Monastery, and Ganden Monastery conducted special religious rituals for national protection. State protector deities like Lhamo and Gadong were invoked to defend the land.

Despite repeated Tibetan protests demanding that Britain halt its advance, British forces continued constructing roads and military facilities near the frontier.

The Russian Factor and British Anxiety

At the same time, a new dimension emerged: Russia.

The Buryat monk and diplomat Agvan Dorzhiev (Dorjiev) encouraged closer ties between Tibet and Russia. The 13th Dalai Lama, Ngawang Lobsang Thupten Gyatso, established communication with Russia and even visited Saint Petersburg, where he met Nicholas II.

Russian officials reportedly expressed goodwill and explored possibilities of deeper relations. There were even discussions of sending Russian representatives to Tibet.

These developments deeply alarmed British authorities in India. They feared that Tibet might fall under Russian influence as part of the larger “Great Game” rivalry between the British and Russian empires.

Intelligence and Mutual Suspicion

British India intensified intelligence activities. Agents disguised as Ladakhi monks were reportedly trained in Tibetan language and culture to gather information inside Tibet.

Meanwhile, the Qing (Manchu) government also viewed Tibet’s foreign contacts with suspicion. Although Qing influence in Tibet was weakening, Beijing remained sensitive to any independent foreign diplomacy conducted by Lhasa.

Thus, by the late 19th century:

- Britain suspected Tibet of aligning with Russia.

- Tibet suspected Britain of preparing invasion.

- The Qing court doubted Tibet’s foreign autonomy.

This atmosphere of mutual misunderstanding and geopolitical rivalry laid the groundwork for open military confrontation, culminating in the British expedition to Tibet in the early 20th century.

The First Phase of the Anglo-Tibetan Conflict (1875–1887)

The first phase of armed tension between Tibet and Britain began in 1875 (Wood Pig Year). At that time, several British nationals entered Sikkim, claiming they were merely traveling for sightseeing and mountain exploration. However, reports soon reached Tibetan authorities that these individuals had approached border areas such as Nathu La and nearby passes.

When questioned, Sikkimese officials responded that the British were only on leisure trips and wished to build a small rest house for travelers. The Tibetan government firmly rejected this request, suspecting that such construction could serve as a military foothold.

British Mission and Tibetan Refusal

Soon afterward, further reports arrived stating that around ten British representatives, carrying official documents issued under Qing authority, intended to enter Tibet. Their declared purpose was to meet the Dalai Lama and discuss Anglo-Tibetan trade and diplomatic relations.

The Tibetan government convened a major assembly and issued a decisive response:

- Regardless of whether British subjects carried Qing permits,

- They would not be allowed to step onto Tibetan soil without direct Tibetan approval.

Orders were sent to frontier districts such as Phari, Gyamo, and other border strongholds to strictly enforce the ban. Local officials and informed community leaders continuously submitted reports to the Kashag (Tibetan cabinet), urging vigilance.

Repeated national assemblies were held in Lhasa. Oaths were sworn to defend the frontier. The government resolved to strengthen border defenses at Lungthur (Lingtu area), construct fortifications, and station troops to prevent forced entry.

Communication with the Qing Court

At the same time, the Qing amban in Lhasa suggested reporting the situation to the Qing emperor. Tibetan envoys were dispatched to Beijing, but due to long travel distances, a response took nearly a year.

The Qing court’s reply advised maintaining peace along the border and avoiding escalation. However, from the Tibetan perspective, Britain had already advanced aggressively toward Lungthur, and its proposals—such as establishing trade posts in Shigatse and western Tibet—were seen as unfounded and unlawful demands.

Tibetans believed that yielding at this stage would amount to opening the “gate” of the country to foreign control.

Construction of Lungthur Fort (1886–1887)

By 1886 (Fire Dog Year), British officials in Sikkim, reportedly led by a commander identified in Tibetan records as “Meikolo,” renewed requests to build a rest station at Kongbuk. The Tibetan government interpreted this as preparation for military encroachment.

In response, Tibet dispatched senior officials, including Druk Gyal and central military commander Tsarong Wangchuk Gyalpo, along with representatives from the Three Great Monasteries and Tashilhunpo. After surveying the area with local experts, they proposed constructing a defensive fort at Lungthur.

The Kashag approved the plan. A new dzong (fortress) and inspection station were built in 1887. According to Tibetan historical chronicles, religious consecration ceremonies were performed, including the installation of protector deity images such as Pehar and Dorje Drakden.

A small garrison was stationed there—one commander and about twenty-five soldiers—supported by additional frontier troops from Lhobrakh, Mon, Tsona, and Dingri.

British Protest Through Beijing

Meanwhile, the British representative in Beijing lodged complaints with the Qing government. Britain accused Tibet of obstructing trade and demanded:

- Withdrawal of Tibetan troops from Lungthur,

- Demolition of the newly constructed fort,

- Removal of defensive barriers.

British officials even warned that destroying the fort and advancing into Tibet would be militarily easy, but claimed they preferred diplomatic resolution.

Under pressure, the Qing court instructed that the Lungthur fort be dismantled and Tibetan troops withdrawn. However, the Tibetan government responded cautiously. While expressing respect for the Qing emperor in accordance with the traditional “priest-patron” relationship, Tibetan authorities argued:

- Lungthur was unquestionably Tibetan territory.

- It functioned as the “gateway” of Tibet.

- Opening it would be equivalent to inviting intrusion.

They emphasized that surrendering control of the border would risk losing their land entirely.

A Delicate Balance: Obedience and Resistance

At this stage, the Tibetan government faced a complex dilemma:

- On one side, it was expected to show deference to Qing imperial authority.

- On the other, public sentiment in Tibet strongly supported firm resistance against British expansion.

Tibetan society widely viewed the defense of Lungthur as a matter of sovereignty and survival. Therefore, complete compliance with Qing demands was politically and morally difficult.

This tension marked the true beginning of open confrontation. Though full-scale war had not yet erupted, fortification, troop mobilization, diplomatic protest, and strategic positioning had already transformed frontier disputes into a serious geopolitical conflict.

The events at Lungthur would soon escalate further, leading to direct military clashes between Tibetan and British forces in the years that followed.

Sikkimese Support and Intelligence Flow

During this tense frontier period, some people from Sikkim—sharing religious and ethnic ties with Tibet—secretly passed British military information to the Tibetan side. Reports suggest that details of British strategic planning, including their use of long-range firearms and artillery, were known in advance.

According to these accounts, British commanders understood that in close combat Tibetan fighters were fierce, physically strong, and skilled with swords and spears. They were also adept at forest warfare, ambush, and sudden charges. Therefore, British strategy emphasized:

- Avoiding hand-to-hand combat

- Relying on artillery and modern rifles

- Defeating Tibetan forces from a distance

This reflects the broader military imbalance between a modern imperial army and a traditionally equipped Himalayan force.

The 1887 British Advance Toward Lungthur

In 1887, under the command of a British officer recorded in Tibetan sources as “Nael” (likely referring to a British field commander stationed in Sikkim), more than 2,000 Gurkha troops advanced toward Lungthur. They were supported by:

- Modern military supplies

- Around 1,000 laborers (coolies)

- Large numbers of horses and pack animals

A forward base was established near Lungthur, and British forces began surveying the terrain in preparation for a formal assault.

The 1888 Assault on Lungthur

In 1888, British troops launched a sudden attack on Lungthur. Tibetan forces responded with determined resistance. Initial clashes reportedly resulted in several British casualties, forcing a temporary British withdrawal.

However, the following day the British resumed their offensive with heavier firepower. Their battle formation involved:

- Artillery bombardment “like rain”

- Coordinated cavalry and infantry movement

- Systematic forward advancement under cover of gunfire

Tibetan forces, meanwhile, adopted guerrilla-style tactics:

- Hiding in forested areas

- Firing arrows from cover

- Launching synchronized frontal charges

War cries echoed across the battlefield as Tibetan soldiers advanced with swords, spears, axes, and stones. The fighting was intense and close-quarters.

Among the Tibetan casualties was Dingri Centurion Ngödrup Tsering, along with eighteen other frontline officers. British losses were also significant, reportedly exceeding one hundred soldiers.

Ammunition Shortage and Turning Point

At a critical moment, Tibetan ammunition supplies ran out. A shouted call requesting more ammunition was overheard by Tibetan-speaking personnel within British ranks. This intelligence shifted the balance of the battle.

Seizing the opportunity, British forces intensified artillery bombardment from a distance and launched a renewed advance. Despite fierce resistance—including rolling boulders and direct combat—the technological superiority of British weaponry proved decisive.

The Tibetan defenders, though brave and determined to protect their land and religion, lacked modern military strategy and equipment. Ultimately, Lungthur fell to British control.

Retreat to Nagthang Plateau

After withdrawing from Lungthur, Tibetan forces regrouped at Nagthang, a high plateau approximately 13,550 feet above sea level. Defensive positions were prepared, and reinforcements assembled.

However, British forces launched another sudden artillery barrage, dispersing Tibetan troops across surrounding hills and forests.

Even so, local militias and regional forces carried out surprise attacks on British camps, inflicting further casualties. Yet the imbalance in weapons, training, and logistics made sustained resistance extremely difficult.

Criticism and Folk Satire in Lhasa

News of the defeat reached Lhasa, where public criticism emerged. Satirical songs circulated mocking certain commanders who had retreated. Tibetan historical chronicles record verses criticizing officials such as:

- Surkhang (a military commander who reportedly fled)

- Other administrative officers who withdrew early

These songs reflected public frustration over leadership failures during a moment of national crisis.

Appeal to Nechung and Renewed Mobilization

Following the loss, reports were sent to Lhasa by senior officials including Lhaku Yeshe. The Tibetan government consulted the Nechung Monastery oracle for guidance.

The oracle’s message reportedly emphasized perseverance:

“What has been begun must be brought to completion.”

With renewed determination, additional regional militias were mobilized from areas including Phongyö, Olka, Lhobrakh, Dharma, Lhakhang, and Serdzong. Approximately 2,800 troops were dispatched to reinforce the frontier.

Historical Significance

The clashes at Lungthur in 1887–1888 marked a decisive escalation in the Anglo-Tibetan frontier conflict. They demonstrated:

- Tibetan courage and strong local resistance

- British technological and strategic superiority

- The limits of traditional warfare against modern imperial armies

These early battles set the stage for further British advances into Tibetan territory and shaped the geopolitical trajectory that would culminate years later in the larger British expedition into Tibet.

The events remain a powerful symbol in Tibetan historical memory—of bravery, sacrifice, and the harsh realities of imperial-era frontier warfare.

The Role of the Qing Amban and the “Calcutta Convention”

During this critical stage of the conflict, a British representative based in Calcutta—identified in Tibetan sources as “Asib”—arrived in Tibet through connections with leading figures in Sikkim, including prominent lamas and newly established guest houses. He conveyed the message that peaceful relations between Britain and Tibet would be beneficial. However, he also claimed that because Tibet had fundamentally refused to recognize British trade relations, Britain had been compelled to enter Tibetan territory.

At the same time, letters were reportedly sent in the name of the Qing emperor, suggesting an intention to mediate between Tibet and Britain. The Qing government conveyed orders discouraging further military confrontation.

The Qing amban Sheng Tai personally came to the battlefield area and ordered the withdrawal of more than ten thousand Tibetan troops stationed at Dor-mo Rinchen Gang (a strategic position near the frontier). His intervention was framed as an effort to prevent escalation.

However, while negotiations and withdrawal orders were being discussed, the British side was secretly reinforcing its military presence rather than retreating.

Tibetan Reaction: Resistance and Ritual

The Tibetan side, shaken by the setback at Lungthur, did not yield easily. Anti-British sentiment intensified. Public speeches, denunciations, and calls for resistance were widely proclaimed.

Beyond military measures, Tibetans also turned to religious rites:

- Offerings to protective deities

- Ritual smoke offerings (bsang)

- Prayers to local gods and naga spirits

There was strong hope that divine protection would help expel the invading forces swiftly from Tibetan soil.

The So-Called “Calcutta Treaty”

Through negotiations involving Amban Sheng Tai—who claimed full authority as the representative of the Qing emperor—a ten-point agreement was concluded, known in Tibetan accounts as the “Calcutta Convention.” This refers to the Convention of Calcutta, signed between Britain and the Qing government.

From the Tibetan perspective, this was an unequal treaty. It was negotiated without genuine Tibetan participation, yet it directly affected Tibetan territory and frontier arrangements.

After this agreement, many Tibetans came to believe that the Qing dynasty had acted in accordance with British interests rather than protecting Tibetan sovereignty. A new and painful awareness emerged: decisions concerning Tibet’s borders were being made without Tibet’s consent.

For patriotic Tibetans who had hoped for decisive resistance, this realization was deeply disheartening. Their aspirations seemed to vanish “like clouds dissolving into the sky.”

Reasons for Tibet’s Defeat in the First Anglo-Tibetan War

The first phase of the Anglo-Tibetan conflict ended in defeat for Tibet. Several key factors contributed to this outcome:

1. Lack of Military Training

Most Tibetan soldiers were not professionally trained. When war broke out, the government mobilized:

- Lay civilians between ages 18 and 60

- Local militias

- Non-monastic males, regardless of prior experience

They were summoned quickly and often required to provide their own provisions.

2. Weak Organization and Discipline

Many units consisted of regional militias unfamiliar with coordinated military structure. There was:

- No standardized uniform

- No consistent chain of command

- Limited experience in modern battlefield tactics

This lack of structure led to confusion during engagements.

3. Inferior Weaponry and Logistics

Tibetan forces relied largely on:

- Matchlock rifles

- Traditional swords and spears

- Limited artillery

- Inadequate ammunition supplies

By contrast, British forces possessed modern rifles, artillery, and organized logistical systems.

4. Absence of Strategic Planning

Modern military planning and tactical deployment were minimal. Defensive positions were often improvised rather than systematically designed.

5. Political Constraints from the Qing Amban

Amban Sheng Tai reportedly discouraged full-scale resistance and created obstacles to launching a unified offensive strategy. This limited Tibet’s ability to respond decisively.

Contemporary Observations

A Japanese account cited in political histories described the situation starkly. It noted that when Tibetan forces first confronted British troops around midday, they were unable to mount an effective counterattack.

According to this account:

- British troops faced challenges mainly from terrain and climate, not from Tibetan military strength.

- Tibetan fighters lacked training and planning necessary to confront modern weaponry.

- Mobilization followed traditional custom: when war arose, all eligible men were called up, but without proper preparation.

- Soldiers lacked uniforms, discipline, and coordinated structure.

The description adds that when approaching the enemy, Tibetan fighters would shout loudly to create the impression of large numbers. Sometimes this tactic briefly discouraged immediate British advance. However, once artillery fire began, many dispersed rapidly to preserve their lives.

While such accounts may reflect external perspectives and possible bias, they highlight the profound military imbalance between a traditional Himalayan defense force and a modern industrial empire.

Historical Reflection

The first Anglo-Tibetan conflict illustrates the collision between:

- A deeply religious, tradition-oriented society

- A rapidly modernizing imperial military power

It also marked a turning point in Tibetan awareness of international politics. The realization that external powers could negotiate Tibet’s borders without Tibetan consent profoundly shaped political consciousness in the decades that followed.

The defeat was not merely military—it was psychological and geopolitical, signaling the beginning of a new and uncertain era in Tibet’s relations with global powers.

The Second Phase of the Anglo-Tibetan War (1903–1904)

After Tibet refused to implement the unequal provisions of the earlier frontier agreement—commonly associated with the Convention of Calcutta—tensions with Britain escalated sharply. British authorities grew increasingly frustrated, claiming that Tibet had failed to cooperate in opening trade negotiations.

They demanded that representatives of the Tibetan government—or envoys connected to the Dalai Lama—meet British officials to discuss trade and border issues. Tibetan officials, including high-ranking ministers and military commanders, were appointed to engage in talks near the Sikkim–Tibet frontier.

However, even as diplomatic exchanges were proposed, British troops began advancing toward Tibetan territory.

British Military Advance into Southern Tibet

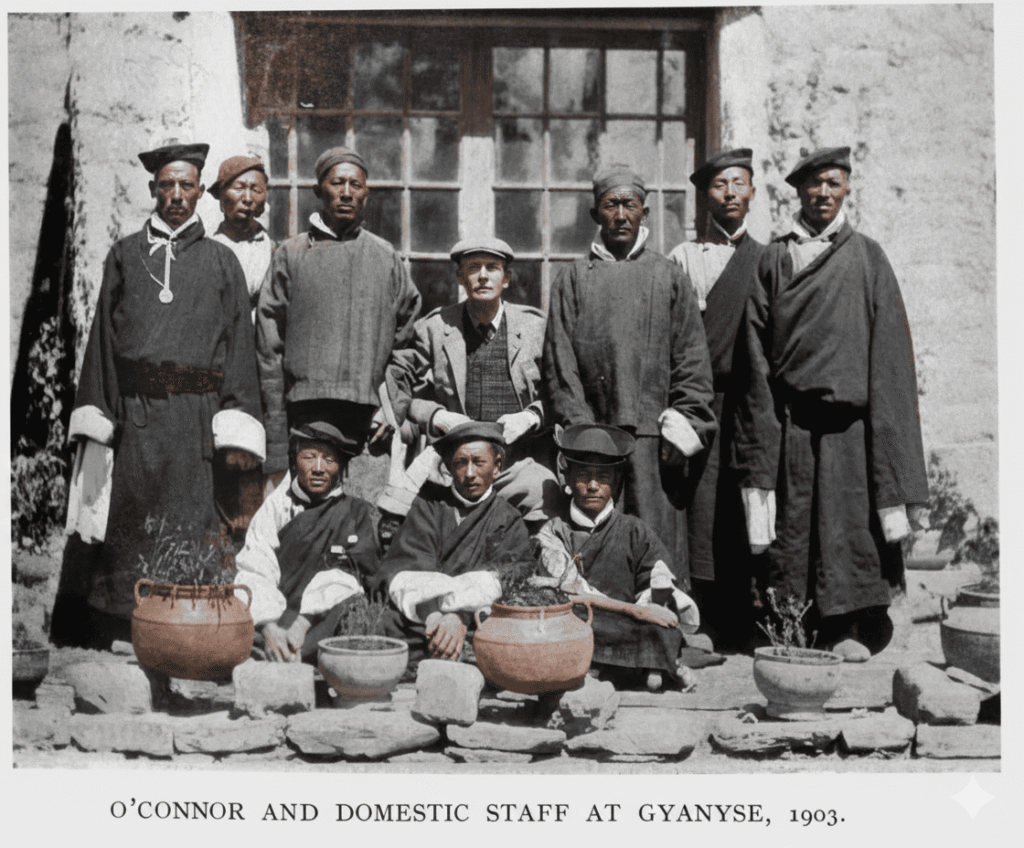

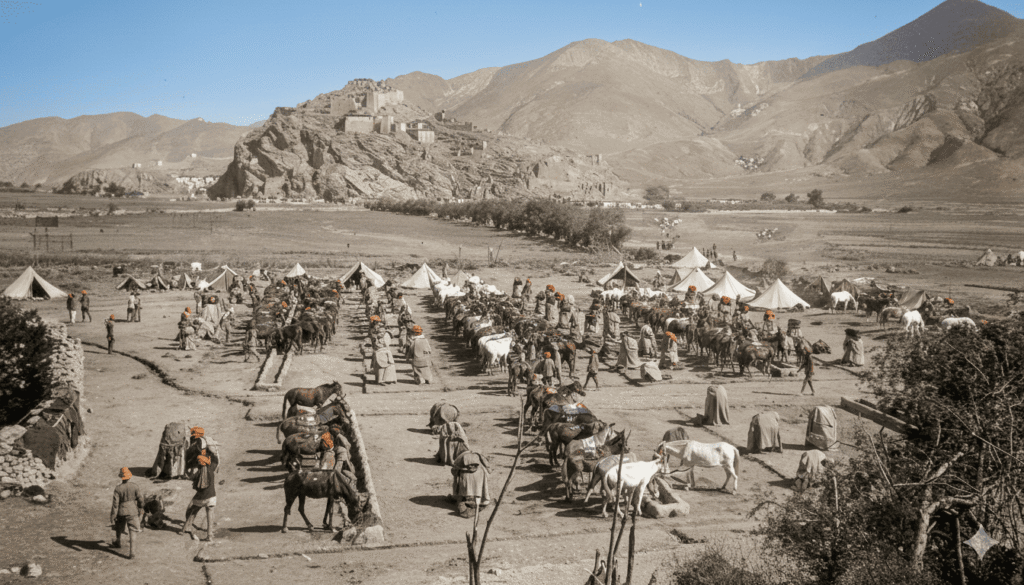

In 1903, under the leadership of Colonel Francis Younghusband, a large British-Indian expeditionary force crossed from Sikkim into Tibet.

The force included:

- British officers

- Indian infantry

- Gurkha soldiers

- Artillery units

- Transport corps and logistical staff

Their stated purpose was negotiation—but their steady military advance suggested otherwise.

By late 1903, British troops had crossed Jelep La and moved toward Phari (Phagri), gradually pushing northward in the direction of Gyantse.

Tibetan Mobilization and Defensive Preparations

In response, the Tibetan government convened a large assembly to discuss national defense. A consensus emerged:

- Resist foreign invasion at all costs.

- Mobilize reinforcements from Ü-Tsang, Kham, and Amdo.

- Block mountain passes and key roadways if negotiations failed.

Troops were positioned at strategic locations including:

- Chumik Shenko (Guru)

- Dochen

- Kala

- Chalu

- Sram (Upper and Lower divisions)

Stone barricades were constructed along mountain slopes. Despite limited modern weaponry—most soldiers carried traditional rifles, swords, spears, and shields—morale was strong.

Tibetan commanders and Panchen Lama representatives attempted further peaceful dialogue. Yet British demands remained uncompromising.

The Massacre at Chumik Shenko (Guru), 1904

On the 15th day of the first Tibetan month in 1904 (March 31, 1904), British forces approached Tibetan positions at Chumik Shenko (also known as Guru).

British officers sent a message claiming that they wished to meet authorized Tibetan negotiators to finalize peace discussions. Tibetan representatives gathered in the valley to meet them. Both sides agreed—at least verbally—to lay down arms during the talks.

Tibetan troops extinguished their match fuses. British soldiers claimed they had removed ammunition from their rifles.

However, British troops secretly retained loaded ammunition in their machine guns and reserve chambers.

During the negotiations, a British officer suddenly opened fire. Within moments, machine guns and rifles unleashed devastating volleys into the densely gathered Tibetan ranks.

The result was catastrophic.

- Approximately 500 Tibetan soldiers were killed.

- Around 430 were wounded.

- Many were shot at close range.

- Survivors attempted desperate charges with swords against modern firearms.

This event became known as the Guru Massacre.

Eyewitness accounts describe Tibetan fighters rushing forward despite overwhelming firepower. Some charged directly into gunfire rather than retreat. Their resistance became legendary in Tibetan memory.

The site of Chumik Shenko remains one of the most tragic battlefields of modern Tibetan history.

Aftermath: British Advance Toward Gyantse and Lhasa

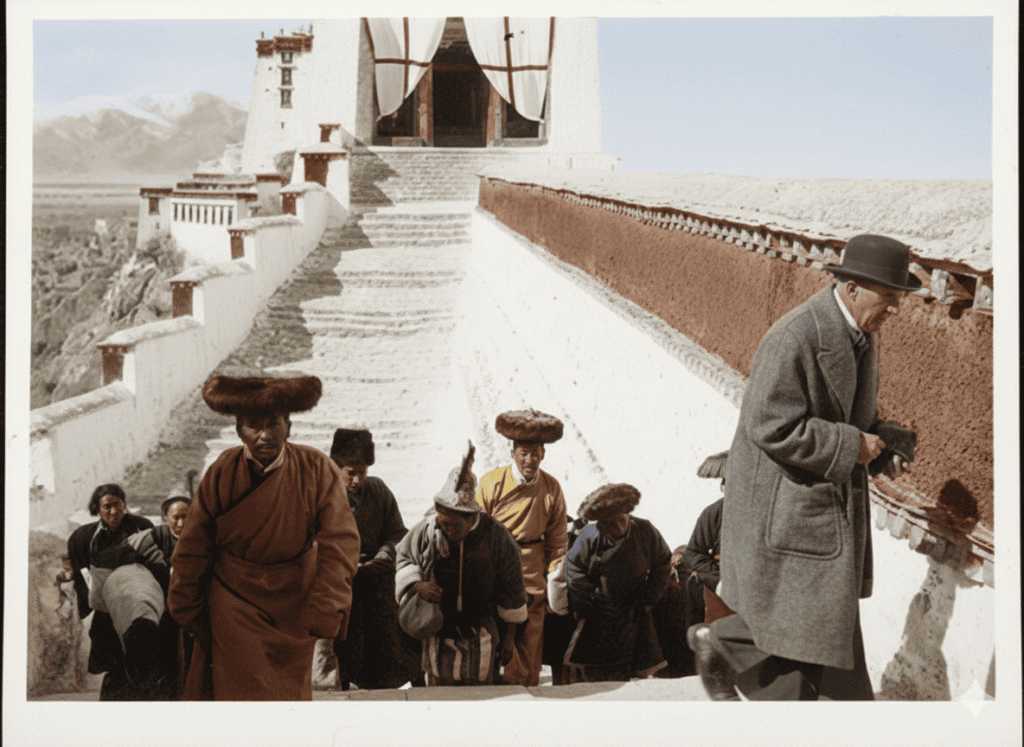

Following the massacre, British forces continued advancing toward Gyantse, Tibet’s important military stronghold.

Despite fierce resistance, modern artillery and Maxim machine guns gave the British a decisive advantage.

The campaign ultimately culminated in the British entry into Lhasa in August 1904. There, the Treaty of Lhasa was imposed on Tibet, marking a turning point in Tibetan foreign relations.

Historical Significance

The second phase of the Anglo-Tibetan War revealed:

- The immense technological gap between a modern imperial army and a traditional Himalayan defense force.

- The vulnerability of Tibet in the age of global imperial expansion.

- The deep patriotic resolve of Tibetan soldiers despite overwhelming odds.

The memory of Chumik Shenko (Guru) remains deeply embedded in Tibetan historical consciousness. The sacrifices made there are remembered as symbols of courage, national defense, and resistance against foreign domination.

For Tibetans, the events of 1904 were not merely a military defeat—they were a defining moment of collective memory that shaped political awareness for generations.

The Battle of Gyantse, 1904: Heroic Resistance in Central Tibet

After the devastating defeat at Chumik Shenko (Guru), Tibetan forces regrouped and withdrew toward the Gyantse region. The British expedition led by Francis Younghusband continued its aggressive advance deeper into Tibet.

Despite heavy losses, Tibetan commanders gathered approximately 2,300 troops and reorganized defensive lines. Reinforcements were mobilized, and preparations were made to defend the strategic stronghold of Gyantse.

British Advance and Destruction Along the Route

As British troops moved northward, they burned monasteries and settlements along the way. Among the sites damaged were:

- Palkhor Monastery

- Kumbum Stupa

Their forces reached the vicinity of Shalu and surrounding areas. At night, Tibetan troops under the leadership of commander Tashi Lingpa launched surprise counterattacks, killing and wounding approximately 60 British soldiers.

For three consecutive days, fierce fighting continued. Using the natural terrain to their advantage, Tibetan defenders rolled rocks and logs down slopes onto advancing troops. Around 230 British casualties were reportedly inflicted during these engagements, while roughly 80 Tibetan soldiers were killed or wounded, including prominent commanders such as Lhagyel and Samten.

Despite courageous resistance, Tibetan forces were unable to halt the better-armed British army.

The Siege of Gyantse Dzong

Soon after, the major confrontation known as the Battle of Gyantse began.

Gyantse Dzong, the fortress towering above the town, became the focal point of resistance. Under the leadership of Tibetan commanders such as Tashi Lingpa and Chaktrakpa, defensive preparations were strengthened inside and outside the fortress.

Marksmen and artillery handlers were positioned along the iron walls and fortifications. However, British forces deployed modern artillery, Maxim machine guns, and large quantities of ammunition.

From surrounding hills, British artillery units launched heavy bombardments. Shells rained down on Tibetan defensive positions. Even as Tibetan forces provided reinforcement to Gyantse Dzong, casualties mounted steadily.

The Assault on the Monastery and Fortress

British troops attacked simultaneously from multiple directions. Protected by continuous artillery fire and machine-gun cover, they advanced toward the monastery walls.

The iron gates and main entrances were sealed by Tibetan defenders. Despite overwhelming firepower, the defenders refused to surrender.

A fierce hand-to-hand struggle followed.

Kongpo soldiers, including a warrior remembered as Adar Nyima Drakpa and his companions, wrapped cloth around their heads, raised swords high, and charged into enemy lines shouting battle cries. Many British soldiers fell under close combat.

After several hours of intense fighting:

- Around 120 British troops were reportedly killed or wounded.

- The stone courtyards were said to have run red with blood.

A popular folk verse later commemorated the resistance:

“When the Kongpo warriors arrived,

The British troops fell to the ground.

The stones of the monastery courtyard

Were filled with red blood.”

Yet despite the bravery, the British army eventually gained control of strategic high ground after a local informant revealed terrain weaknesses. Artillery was repositioned to higher ridges, allowing devastating fire to fall upon Tibetan positions.

Explosive charges breached sections of the fortress walls. British troops stormed inside.

Final Resistance and British Advance Toward Lhasa

Although Tibetan forces continued fighting at key passes and chokepoints, coordination difficulties and leadership disruptions weakened the overall defense.

High-ranking officials, including Yutok (a senior military administrator), attempted to organize further resistance. However, British military superiority proved decisive.

With Gyantse effectively subdued, British forces advanced toward Lhasa.

In August 1904, they entered the Tibetan capital, culminating in the signing of the Treaty of Lhasa, which imposed heavy indemnities and trade concessions on Tibet.

Historical Meaning of the Gyantse Resistance

The Battle of Gyantse stands as one of the most dramatic episodes of the 1903–1904 British invasion of Tibet.

It demonstrated:

- The courage and determination of Tibetan defenders.

- The devastating impact of modern imperial military technology.

- The strategic importance of Gyantse as the gateway to central Tibet.

Although ultimately defeated, the resistance at Gyantse became a symbol of patriotism and sacrifice in Tibetan historical memory.

The events of 1904 marked a turning point in Tibet’s encounter with global imperial powers, shaping its political trajectory for decades to come.

British expedition to Tibet (1904) – The Aftermath of the Anglo-Tibetan War

The Anglo-Tibetan War of 1903–1904, led by the British mission under Francis Younghusband, marked one of the most dramatic turning points in modern Tibetan history. Its conclusion reshaped Tibet’s political landscape, weakened its autonomy, and left deep economic and cultural scars.

The Dalai Lama’s Departure from Lhasa

As British forces advanced toward Lhasa, the 13th Dalai Lama, Thubten Gyatso, recognized the growing danger. Concerned that mass resistance from monks and laypeople—especially from the great monastic seats—might trigger widespread bloodshed, he issued repeated instructions urging restraint and peaceful handling of the crisis.

On July 13, 1904 (Tibetan calendar), the Dalai Lama transferred governing authority to the Regent and departed Lhasa, traveling north toward Mongolia. His decision was strategic: without strong military capacity or foreign backing, direct confrontation with the British Empire would likely lead to even greater devastation.

British Entry into Lhasa

British troops entered Lhasa in August 1904 and camped near the city. The Tibetan government supplied food and fuel at fair market value but avoided ceremonial reception, maintaining a cautious and dignified stance.

Initial contact between Tibetan officials and the British was tense. Eventually, high-ranking Tibetan representatives met with Younghusband to begin negotiations. The British insisted their objective was to secure diplomatic and trade agreements, claiming no intention to harm Tibet if resistance ceased.

However, isolated violent incidents occurred. In one case, two monks attacked British officers and were killed. Following this, Tibetan authorities tightened internal discipline, organized prayer assemblies, and sought to prevent further unrest.

Diplomatic Pressure and Regional Influence

Representatives from neighboring regions—including Bhutan (led by Ugyen Wangchuck) and Nepal—encouraged Tibet to accept British terms. Britain demanded:

- Opening trade marts between India and Tibet

- Settlement of border disputes

- Compensation for military expenses

- Exchange of prisoners

Tibet faced an impossible situation. Qing China provided little meaningful support, despite Tibet’s appeals to the Manchu court. Meanwhile, Chinese troops were causing disturbances in eastern Tibetan regions such as Nyagrong and Lithang.

With limited military strength and no reliable allies, Tibetan leaders reluctantly chose compromise.

The 1904 Treaty of Lhasa

On September 4, 1904, Tibetan representatives were compelled to sign what became known as the Convention of Lhasa—an unequal treaty imposing heavy financial indemnities and granting Britain significant commercial privileges.

On September 23, 1904, British forces withdrew from Lhasa.

Human and Cultural Losses

The cost of the war was devastating:

- Approximately 18,600 British and Indian troops entered Tibetan territory.

- Tibetan casualties were severe, including soldiers, monks, and civilians.

- Villages and monasteries were burned.

- Precious religious artifacts—gold ornaments, jeweled statues, sacred objects—were looted or destroyed.

- Monasteries such as Gyantse and Ganden suffered heavy damage.

The financial burden of indemnities and reconstruction weighed heavily on both the Tibetan government and ordinary people for many years.

Historical Significance

The 1904 war exposed Tibet’s geopolitical vulnerability. Surrounded by imperial powers and lacking modernization, Tibet faced the harsh realities of global politics.

Yet the memory of the defenders—soldiers and monks who fought at Gyantse and other strongholds—remains deeply honored in Tibetan historical consciousness. Their courage, though unable to prevent defeat, became a symbol of national resilience.

A Legacy Written in Blood and Faith

Tibetan historical poetry remembers the fallen not only as warriors but as guardians of faith and homeland. Their sacrifice is described as a “stone pillar built with patriotic blood,” standing forever in collective memory.

Though the Anglo-Tibetan War ended in political concession, it awakened Tibet to the urgent need for reform and engagement with the modern world—an awareness that would shape the later policies of the 13th Dalai Lama upon his return.

The echoes of 1904 still resonate in discussions of sovereignty, diplomacy, and Tibet’s place between powerful neighbors.