The Rise of Buddhism in Tibet

The story of how Buddhism rose in Tibet is not a single moment of conversion, but a long and dramatic process shaped by kings, queens, scholars, mystics, and even persecution. Spanning several centuries, this transformation reshaped Tibetan culture, politics, philosophy, and identity. What we now call Tibetan Buddhism emerged through waves of introduction, decline, and revival—each leaving a lasting imprint.

Early Tibet Before Buddhism: The Age of Bön

Before Buddhism took root, Tibet was dominated by Bön, an indigenous spiritual tradition deeply connected to nature spirits, ancestral rituals, and shamanic practices. Bön shaped early Tibetan cosmology and royal authority, and it was closely tied to local deities and landscapes.

This spiritual background would later influence how Buddhism adapted in Tibet, blending ritual, symbolism, and meditation in ways unique to the region.

The First Turning Point: King Songtsen Gampo and His Queens (7th Century)

The initial introduction of Buddhism to Tibet began in the 7th century during the reign of King Songtsen Gampo, the first of Tibet’s legendary Three Dharma Kings. A powerful military leader, Songtsen Gampo unified large parts of the Tibetan Plateau and established Lhasa as a political center.

While the king himself showed interest in Buddhism, the deeper influence came through his two consorts:

- Princess Wencheng from the Tang Dynasty of China

- Princess Bhrikuti from Nepal

Both princesses were devout Buddhists and brought sacred Buddhist images, scriptures, and artistic traditions with them. Among the most revered was the Jowo Shakyamuni statue, now enshrined in Lhasa.

The Jokhang Temple and Early Foundations

To house these sacred images, the Jokhang Temple was constructed in Lhasa. Although Buddhism at this stage remained largely confined to the royal court and elite circles, the Jokhang became the spiritual heart of Tibet and a focal point for future devotion.

This period did not see mass conversion, but it laid the institutional and symbolic foundations that made later expansion possible.

The First Major Expansion: The Nyingma Era (8th Century)

The true rise of Buddhism as a national force occurred in the 8th century under King Trisong Detsen, another of the Three Dharma Kings. Determined to establish Buddhism across Tibet, he faced strong resistance from entrenched Bön traditions and local spiritual forces.

To address this challenge, the king invited two extraordinary figures from India—each representing a different approach.

Shantarakshita: Philosophy and Monastic Discipline

Shantarakshita, a renowned Indian scholar-monk, emphasized:

- Ethical conduct

- Logic and philosophical reasoning

- Structured monastic education

However, his rational approach alone struggled to overcome resistance rooted in ritual and local belief systems.

Padmasambhava: Tantra and Transformation

To complement this, Padmasambhava, also known as Guru Rinpoche, was invited. A master of tantric Buddhism, Padmasambhava is credited—according to Tibetan tradition—with subduing local spirits and converting them into protectors of the Dharma.

This blending of Buddhist tantra with indigenous beliefs allowed Buddhism to take deep root in Tibetan soil rather than replacing local traditions outright.

Samye Monastery and the Birth of Tibetan Buddhism

Together, these masters established Samye Monastery, the first Buddhist monastery in Tibet. Samye became a center for:

- Monastic life

- Large-scale translation of Sanskrit texts into Tibetan

- Training of the first Tibetan monks

This era marked the birth of the Nyingma tradition, or the “Old School” of Tibetan Buddhism, which preserves ancient tantric teachings and the tradition of terma (hidden spiritual treasures).

Collapse and Persecution: The Dark Age (9th Century)

The rapid spread of Buddhism faced a severe setback during the reign of King Langdarma in the mid-9th century. Known for his opposition to Buddhism, Langdarma initiated a harsh campaign that included:

- Closing monasteries

- Forcing monks to return to lay life

- Suppressing Buddhist teachings in public spaces

Following his assassination in 838 CE, the Tibetan Empire collapsed into political fragmentation and civil conflict. For nearly a century, centralized support for Buddhism disappeared.

During this period, Buddhist practice survived quietly in remote regions and among small communities, preserving lineages that would later re-emerge.

The Great Revival: The Later Diffusion of Buddhism (11th Century)

The form of Tibetan Buddhism known today largely emerged during the Later Diffusion, or Chidar, beginning in the 11th century. This revival was driven by renewed contact with India and a desire to restore authentic teachings.

Atisha and the Path of Systematic Practice

A pivotal figure of this era was the Indian master Atisha Dipankara, invited to Tibet in 1042. Atisha emphasized:

- Strict monastic discipline

- Ethical living

- A gradual, structured path to enlightenment

His teachings laid the groundwork for what later became known as Lamrim, the “stages of the path” approach that remains central in Tibetan Buddhist study.

Emergence of the Major Tibetan Buddhist Schools

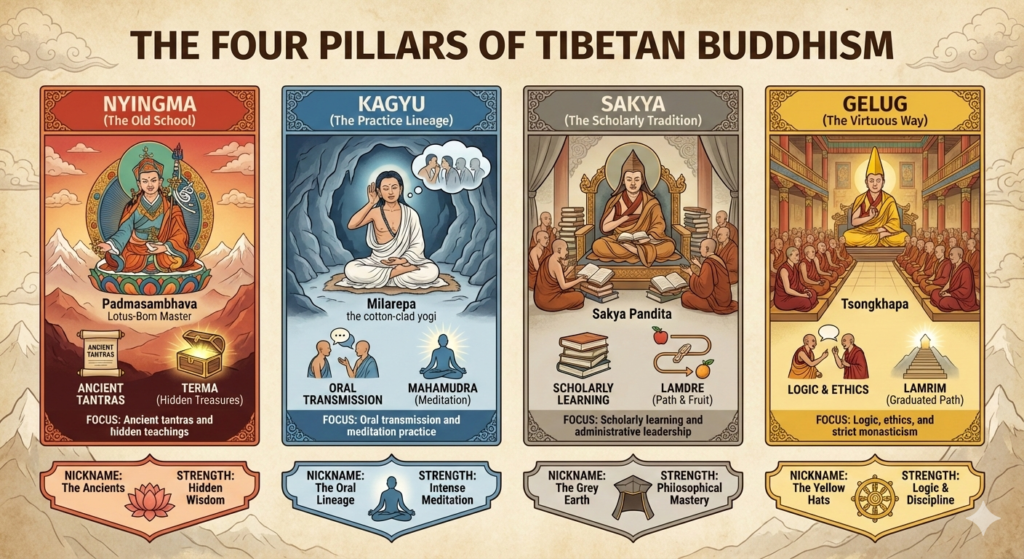

During the Later Diffusion, several lineages crystallized into the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism, each with distinct emphases:

Together, these schools shaped Tibet’s religious institutions, education system, art, and philosophy.

Buddhism as a Defining Force in Tibetan Civilization

Over time, Buddhism transformed Tibet from a society centered on warfare and tribal power into one renowned for scholarship, meditation, and spiritual discipline. Tibetan monasteries became repositories of Indian Buddhist knowledge, preserving texts and philosophies that later disappeared from India itself.

Despite periods of political upheaval and suppression, the Buddhist traditions that took root in Tibet continued to adapt, transmit, and evolve—both within the Himalayas and far beyond.

Tibetan Buddhism and the Legacy of Indian Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism preserves many forms of Buddhism that existed in India around the 11th century, some of which later disappeared in their land of origin. Tibetan masters often rejected the term “Lamaism”, emphasizing that Tibetan Buddhism remained firmly rooted in classical Buddhist teachings rather than being a separate invention.

At the same time, indigenous Bön influences continued to shape Tibetan religious expression. Practices such as prayer flags, incense offerings, and ritual symbolism reflect this enduring interaction between Buddhism and Tibet’s native traditions.

Tibetan Masters and the Ongoing Evolution of Buddhism

Beyond foreign influence, Tibetan masters themselves played a central role in developing Buddhist philosophy, meditation systems, and institutional structures. Across different periods, their contributions ensured that Buddhism in Tibet was not merely adopted, but deeply transformed and localized, giving rise to the rich and diverse traditions seen today.